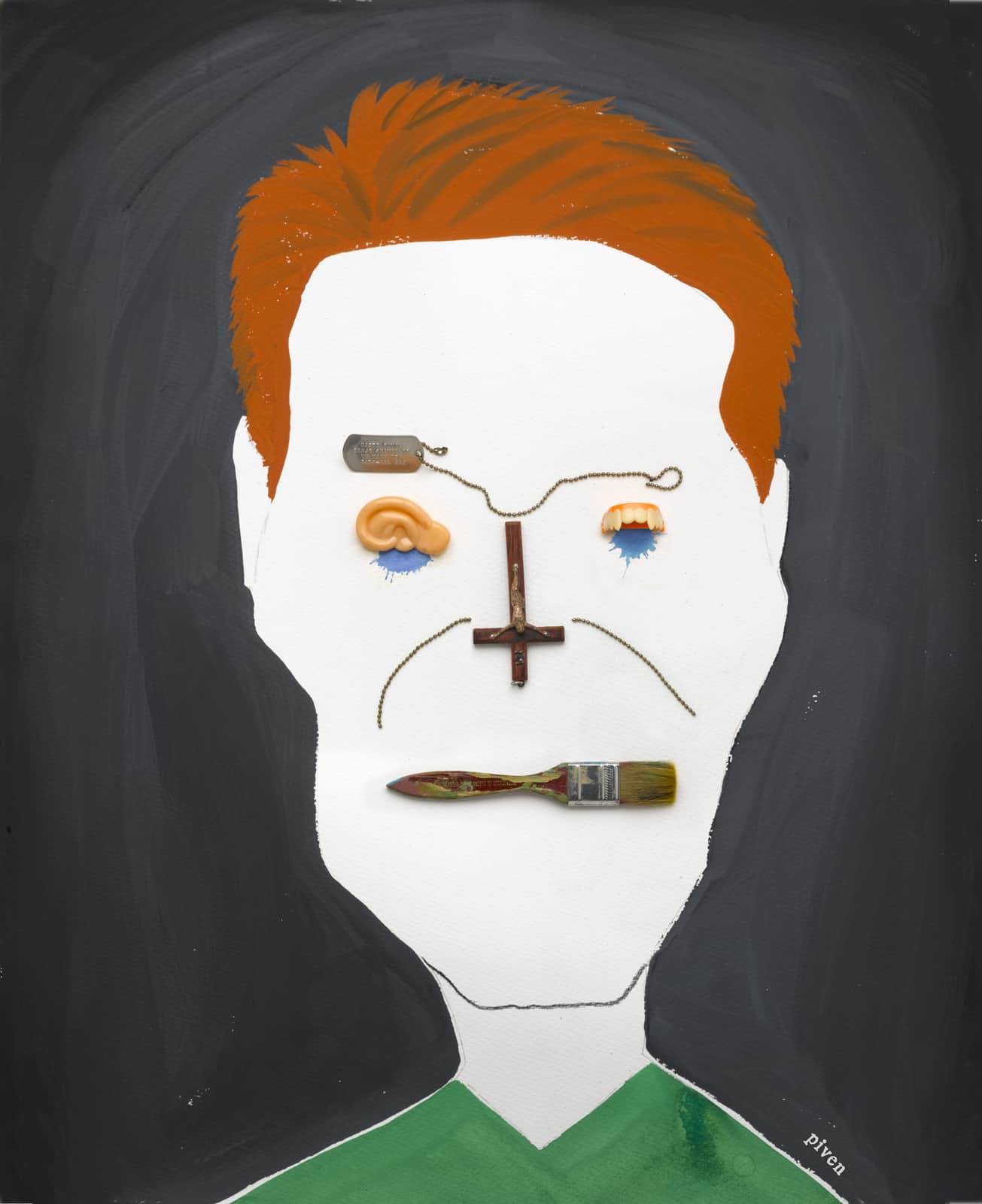

ILLUSTRATION BY HANOCH PIVEN

Willem Dafoe is not an im-pressionist, interpreter, or even, strictly, an actor. “I’m a doer,” says the 63-year-old, whose doing puts him in both art installations and blockbusters. With roots in The Wooster Group, New York’s late-’70s experimental theater ensemble, Dafoe acclimated to vigorous extremes early on, which well served a career of film roles that has covered the bad (Spider-Man villain Green Goblin), the ugly (rotten-toothed Wild at Heart psycho Bobby Peru), the good (saintly Sergeant Elias in Platoon) and the very, very good (the title figure in The Last Temptation of Christ). In 2012, Dafoe told a reporter he felt as much a dancer as an actor: “I’m much more comfortable with the word ‘performer.’”

His performance in this month’s At Eternity’s Gate confirms something else we’ve long sensed about Dafoe: The actor himself is a work of art. Every scene of painter/filmmaker Julian Schnabel’s Vincent van Gogh biopic rests on the lean, sinewy, sharp-featured masterwork who was cast to incarnate the Dutch genius, his long fingers holding a wedge of chalk as if sculpted by Michelangelo. But this is no sun-dappled Merchant Ivory idyll. A hyperimmersive, loosely structured glimpse into the astoundingly productive last two years of van Gogh’s life, At Eternity’s Gate shows the painter’s world through long vistas and brief flashes—a scintillating reality van Gogh moves through at an often frantic pace. Dafoe’s boots scythe through grass and stomp across landscapes that aren’t pretty but jaggedly, brutally beautiful—sublime in the way the devout van Gogh would define the word: evoking terrified, ecstatic awe. “I knew I’d be painting,” Dafoe recalls. “Julian was very clear that he wanted us to be with this man in an experiential way. Learning to paint really rooted me in the process of inhabiting the van Gogh we created.” Calling from a film shoot in Alberta, Dafoe discussed his communion with artists of all stripes, the importance of flexibility, and what it’s like having “the embodiment of pure evil” for a face.

Besides the striking physical resemblance, what drew you to portray van Gogh?

Well, Julian I’ve known for years. I’d been to his studio—he’s painted portraits of me. And the fact that he was a painter making a film about a painter intrigued me. When you learn something new, it really makes you flexible to take on another point of view.

What were painting lessons with Schnabel like?

Always out in nature. First, I went to his place in Montauk, watched him paint, familiarized myself with the materials—how to hold a brush, how to touch the canvas, how to mix colors—and then we would start to look at things. The first thing that I painted totally by myself was a cypress tree in Arles. I started painting it, and Julian said, “No, wait, wait, wait. Look. Look. You’re trying to paint a tree. Look at what you’re seeing.”

Huh?

I was trying to paint what I thought I was seeing rather than what I wasseeing. Julian said, “Look, you don’t see a tree. See that dark part? Paint that. That light part? Paint that.” And that’s the shift that gets you away from representation and into something being born. As van Gogh said, “It’s all in nature—I just have to free it.” That’s powerful. And it comes from painting the light, seeing the colors, watching something emerge on its own.

In the film, the audience sees it happen in the bleak room in Arles, when you look over at muddy shoes that you just took off.

Right. And when you see me paint those shoes, I painted those shoes. Of course, there are cuts—you just can’t watch a guy paint for 50 minutes.

The phrase watching paint dry comes to mind.

Exactly. And I got guidance from Julian and this French painter, Edith Baudrand, as we shot. But I did paint it pretty much in real time. And when you first look at it, you see all the wrong colors—just blobs, nothing makes sense—and then you see it come together not just as a representation, but kind of as those shoes actually are.

That first scene in Arles looks bone-chillingly cold, with your numb fingers struggling to unbutton your coat. How often did climate and conditions help you create these moments?

Oh God, often. In Arles, it was freezing. In his letters, van Gogh talks about this wind, and I have to say it really was quite brutal. And there’s the fact that we were shooting in the actual places as much as possible. That really gets under your skin, because it’s factual, it’s like a relic, something that’s tangible, and certainly roots you. The same trees, the same architecture, the same landscape that van Gogh saw and painted. The crew was very small, and [director of photography] Benoît Delhomme and I were dance partners, particularly in the unscripted and improvised parts, and the camera became a witness to things. We’d shoot quite fast: get to a place, inhabit the room or the landscape, and then shoot the scripted scenes quite quickly. And often we’d be done early, so we’d use the rest of the day to improvise. And those were the times that we went out and painted, or just went walking in the landscape. One time in particular, there’s a scene where it’s at that magic hour of dusk, and I’m going to paint in a field and I’m just overwhelmed by the nature and running around, and I lie down on the ground and pick up clumps of dirt and drop it over my face, get it in my mouth. It was very simple things, and I was really driven just by being in nature in that mask of van Gogh. I felt deeply in tune with that field I was in. And after we left, I found out that that was the field where he painted his last painting.

The film is filled with POV shots that put us inside van Gogh’s head, seeing through his eyes.

For some of those, I was actually operating the camera as I said the lines. This was a brand new thing for me, where it was literally my point of view, and I was framing things. For me, acting is always about doing things, because it gives you a shift in your understanding, so you can abandon your impulses, prejudices, and habits, and become flexible.

For most of the film van Gogh speaks English, but he often goes into a sort of endearingly labored version of French. What languages are you comfortable speaking?

Well, English. I got that one down.

You’re really quite good.

Yeah. [Laughs.] Thanks. And Italian, but I have to study all the time and I’m not fluent in certain circumstances. And because of the Italian, I can read some French and Spanish and other romance languages. But I love languages.

You and your wife, the Italian actress, director, and screenwriter Giada Colagrande, split your time between New York City and Rome—two pretty fine art towns.

Well, I love cities you walk in, and I’ve always loved paintings. But I think it is significant that one of the first places that I traveled a lot to abroad when I was quite young—18, 19 years old—was Amsterdam, when my company toured to a beautiful theater there called the Mickery. That city is the first place that I really lived abroad, and, of course, the Van Gogh Museum is there. It made quite an impression on me, seeing so many of his works in one place at that time. But I’ve gone through phases of loving different artists in different forms—often ones whose work was accompanied by certain narratives. If you aspire to be an artist in any discipline, you tend to look at artists’ lives and how they negotiated them.

I have a distinctive face, a flexible face, but I have nothing to do with it. It’s got its own mind.

In some cases, you’ve even become part of the artist’s work, as with Marina Abramović, with whom you performed onstage in Robert Wilson’s The Life and Death of Marina Abramović. You also performed in Wilson’s surrealist vaudeville The Old Woman. I can’t think of another Hollywood star who could credibly appear opposite Mikhail Baryshnikov in a movement piece.

I’ve always believed in mixing it up. I think I came of age as a performer with The Wooster Group, and that’s something we embraced. It was a theater company, but it was not just a playwright or actors; it was made up of dancers, poets, architects, people from other disciplines. So, constantly, you’d get outside your discipline and apply what you knew in another field, and interesting things would happen.

That sort of crossover aesthetic was at the heart of New York’s downtown scene when you emerged. It seems to be much less common now.

I think that’s true. And there was also a celebration of a kind of amateur aesthetic. Make your own work. Not amateur in terms of the quality but the motivation—doing it for the love of it. People were doing things that wouldn’t naturally assure them that they would have a career. It’s mind-blowing that The Wooster Group is now taught in universities, to kids. And it’s totally reasonable for them to think, “I like that! I want to do that too!” Well, the truth is, when we were making work, we never thought—I mean, we did every show assuming it was our last. It certainly wasn’t [laughs] career-oriented.

In real life, you’re a conventionally handsome man, but The Village Voice once described your face as “the pallidly beautiful embodiment of pure evil.”

Look, I have a distinctive face, a flexible face, but I have nothing to do with it. I mean, I have no control over my face. It’s got its own … mind. But I think as far as the scary thing, I am conscious that I’m a simple kid from the Midwest that came to the big city trying to be an artist and fell a bunch of social classes because I was broke, starting out in the school of hard knocks and all that. And to do that, you have to be familiar with a social mask that heightens all that. So I think that I was quite practiced at being a sweet guy who’s still able to keep the world at bay. I always think of the Bob Dylan lyric, “Little boy lost, he takes himself so seriously/ He brags of his misery, he likes to live dangerously.” Well, that’s what I was.

I wonder if you ever want to get together with Michael Shannon, and some other actors who can weaponize their faces, and just go out for fun and scare the bejesus out of folks?

[Laughs, pause]. You know, no. The only thing I know about my face is that it’s unusual. I know that because people recognize me easily. I always remember I was on a train in a bad neighborhood one time taking my son to the Bronx Zoo when some guys got on the train, and they were looking kind of hard at me. And I thought, Uh-oh, something’s going down here. And then I heard one guy say to the other guy, “No, that’s him. No one looks like that mother******.”