ILLUSTRATION BY HANOCH PIVEN

Alan Alda is in his living room, barefoot. “If you were here, I’d put my shoes on,” he says via phone from New York City. And then, in a rush of honesty: “You don’t know how much you’d appreciate it.”

The actor born Alphonso D’Abruzzo will never outrun his trademark decency. During his half century in the entertainment business, Alda, 83, has brought to life some truly nasty characters: a bilious bartender on the web series Horace and Pete, a venal senator in Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator. But he always brings along what he dryly refers to as “the slime of my amiability,” which is in part the legacy of Hawkeye Pierce, the devoted army doctor and incorrigible scamp he played on M*A*S*H for 11 seasons, beginning in 1972.

Alda is also a best-selling author, a podcast host, and a science enthusiast, and he’s showing no signs of slowing down, despite an ongoing battle with Parkinson’s disease—a diagnosis he shared with the public in 2018. Later this year, he’ll star in Noah Baumbach’s as-yet-untitled Netflix film alongside Adam Driver, Scarlett Johansson, and Laura Dern. “It’s a personal story that doesn’t try hard to be funny, but is funny,” he says carefully, observing the project’s secrecy.

Meanwhile, the fourth season of his podcast, Clear + Vivid, premieres this month, featuring interviews with Madeleine Albright and Carol Burnett, among others. The series stemmed from his work at the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, an organization he helped found at Stony Brook University in 2009 that trains scientists using theatrical improvisation techniques. “I think everybody can benefit from them,” Alda explains. “It opens you up to other people and helps you understand what they’re going through.” With liberated toes, he sat down to discuss his varied career, his long marriage, and why he wouldn’t want to sleep in the same tent as Hawkeye.

In January, you accepted a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Screen Actors Guild. Do you put much stock in awards?

That night I did. It meant a lot to me. Nobody earns an award. People who complain that they don’t get awards sort of amaze me. You’re not entitled to one. An award is always a bonus.

Not many people would call you a complainer—when you revealed your Parkinson’s diagnosis, you said you’ve “had a full life since.” Still, has the disease made everyday life more difficult?

For people who are suffering badly from the disease, much worse than I am, it might sound like I’m taking it too lightly, but at this stage, for me, it’s a terrific puzzle to try to solve. How can I accomplish ordinary tasks more easily? Tying my shoes, buttoning my shirt, keeping my voice in shape. You have to have the strength to attack it. You can’t just fold up and say, “Well, that’s it.” [Michael J. Fox] has been hit hard by it, and he still carries on in his career. It was reassuring to share similar stories. I spend a lot of time doing things to increase my motor ability, like boxing and juggling.

I can’t juggle on a good day anyway.

Well, you have to have been able to juggle to start with. I don’t think it’s a good time to start learning.

Speaking of juggling, you’ve been involved in many different projects and pursuits over the course of your career. Yet M*A*S*H and Hawkeye—one of the most beloved characters in television history—still loom over it all. How do you feel about that?

People ask me that a lot, and I suppose they expect me to say, “I’m sick and tired.” I’ve done a lot of other things in my life, but that’s fine if some people only know me as that character. Hawkeye was not without his flaws, either. What interested me about him was not his heroic moments. He drank too much. He was a smart aleck. He was a skirt-chaser. I could take him in half-hour doses—I don’t know if I’d want to sleep in the same tent with him.

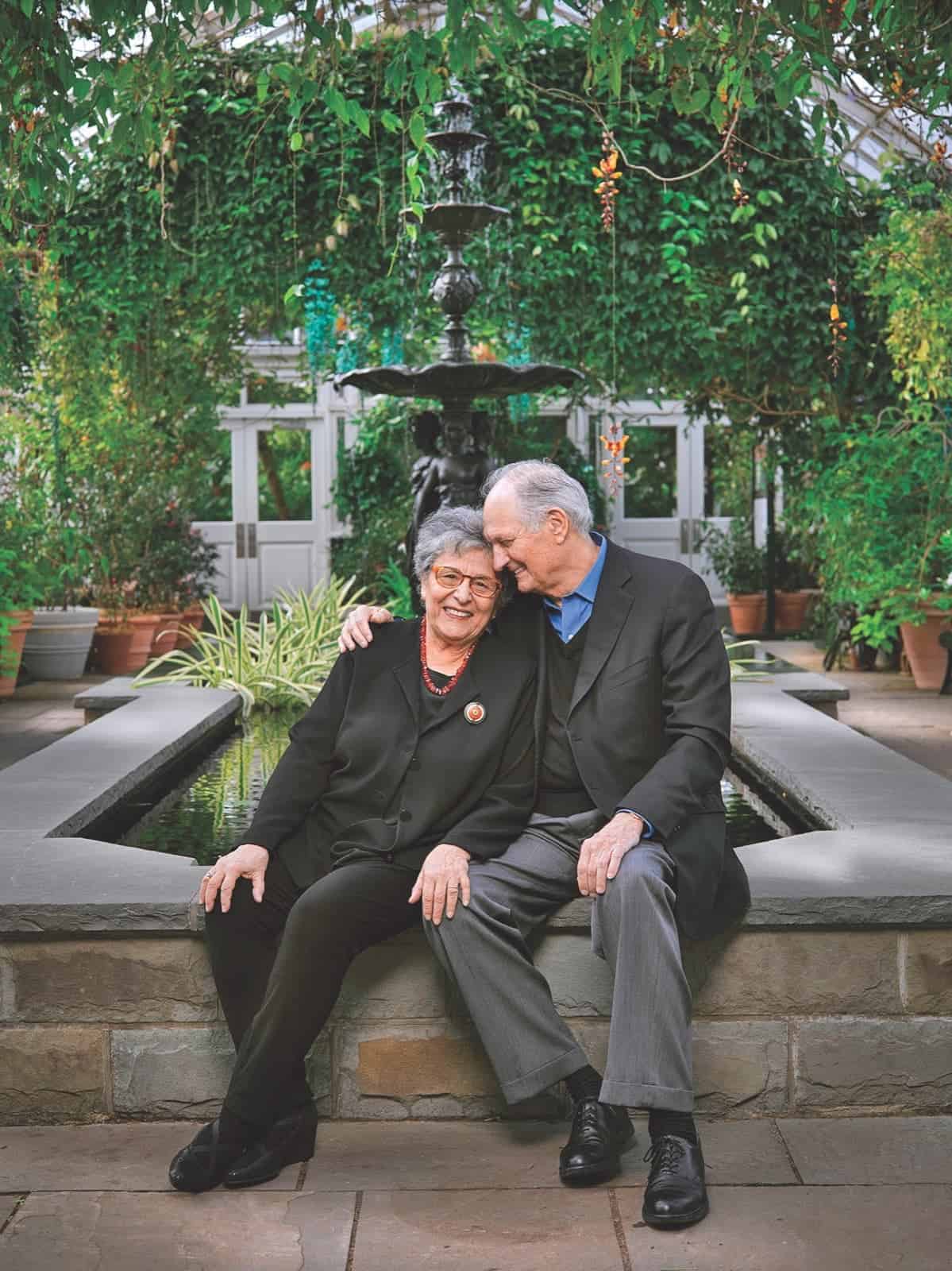

Photo: Alda Communication Training Co.

When you recorded an episode of Clear + Vivid with some of your M*A*S*H co-stars, I was surprised to hear you say that you didn’t consider the series a parable about Vietnam, which seemed like conventional wisdom at the time.

In head writer Larry Gelbart’s mind, there was a resonance with the Vietnam War. Personally, I took it literally, that it was about these people who lived through the Korean War. Gary Burghoff [who played Radar O’Reilly] put it really well—that it wasn’t standing in for Vietnam, it was standing in for allwar. You get universal by being specific.

During the second half of the series, you were writing and directing, and you helmed the final episode. How did you get to the point where you were able to take creative control of the show?

That’s kind of a myth. I wrote and directed a lot of episodes, but I didn’t take any control, ever. The show was always controlled by the producers. I occasionally had opinions, but they were met with counteropinions. I probably would have done a number of things differently. People assumed that my politics were in the show, and they weren’t. I don’t like entertainment that’s propagandistic.

Over the course of your career, what technological or cultural change would you point to as being the most radical—for better or worse?

I’ve seen enormous changes. I’ve seen burlesque die. I’ve seen vaudeville die. I’ve seen movies grow and almost get killed by television, then television almost get killed by cable, and both of them transition into streaming. Storytelling has made a really important shift with bingeing. Now, stories are written with bingeing in mind. It’s a wonderful experience to be so caught up [in an episode] that even though it comes to a conclusion you’ve got to see the next episode, and you’re up until 4 in the morning.

Are you binge-watching anything now? And do you see any shows that are doing what M*A*S*H did, either in terms of reflecting contemporary reality or masquerading as a sitcom while tackling darker subjects?

I’d be able to give you a good answer if I watched more television. I’m too busy doing things. The most amazing thing I’ve seen is an Israeli series called Shtisel. It’s a family drama that is also occasionally funny, but it’s so genuine, and it’s about a world that most of us don’t know.

Science is another world most of us don’t really know. Before founding the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, you hosted the television program Scientific American Frontiers for many years. Your mother suffered from schizophrenia, a terrible and misunderstood disease. Did that influence your passion for science?

I don’t think there was any connection. I think it helped me in my art. As a writer and an actor, you have to carefully observe real human behavior, and I think it made me more observant than I would have been. I had to figure out whether what my mother said was reality or just her reality, and what the rules were that day.

Your primary goal with the center is improving communication skills among scientists. You and your wife, Arlene, have been together for more than 60 years. Would she say you’re a good communicator?

I don’t know if she would have said that when we started. I think she would now. I don’t have flash anger nearly as much. Arlene would sometimes be in the other room and hear me cursing a coat hanger and say, “What is the matter with you?” The coat hanger doesn’t bother me so much anymore.

Is there an example of a scientific idea or principle that you feel has gotten lost in translation or that needs to be better understood by laymen?

Climate change is an obvious answer, because it affects everybody on the planet. There are people who have decided to politicize it, but if there were an asteroid coming at Earth, and in 12 years we knew it was going to wipe us out, we wouldn’t say, “That’s a hoax.” An overwhelming majority of scientists are telling us it’s a threat, but it’s hard to say that without sounding like you’re taking a political position.

You usually end episodes of your podcast by asking seven questions, among them: What do you wish you really understood?

It’s funny, I have the same reaction to that question that almost everybody does, which is, Wait, let me think. I wish I understood why we humans are capable of nurture and torture. It seems like cooperation is so much more beneficial, and yet we have this urge to dominate and kill people.

Another one is, What’s the strangest question anyone’s ever asked you?

I was on vacation, and I was in the dining room of the hotel. A little boy about 6 looked up at me for a really long time, and finally he said, “How did you get out of the TV?”

BY THE NUMBERS

6

Primetime Emmy Awards

251

Episodes of M*A*S*H in which Alda appeared (he was the only actor who was in every episode)

105.9

Millions of viewers who tuned into the Alda-directed M*A*S*H series finale—still the most-watched episode of any network series ever

41

Rank on TV Guide’s 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time list

1956

Year Alda met his future wife, Arlene, when they shared a rum cake that had fallen on the floor at a mutual friend’s dinner party

2009

Year Alda, Stony Brook University, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory created the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science

11

Age of the judges in Alda’s “The Flame Challenge,” in which he asks scientists to explain what a flame is to a kid