It’s easy to think you know Texas—the word is shorthand for longhorns, cowboy boots, dusty trails, and a certain Southern charm. And, to an extent, it’s all true: People in Houston do wear large hats sometimes, and few non-Texans can match their ability to rock cowboy boots in business meetings. But in a city whose top industries include energy, aerospace, and medical science, the Lone Star tropes only get you so far.

Yes, there will be Tex-Mex and pearl snap shirts. But there will also be groundbreaking art, creative fusion food, and the control center that put humans on the moon. All towns have their contradictions, but few accommodate them as comfortably as this Southern city on the bayou. Everything’s bigger in Texas, so there’s plenty of room.

WATCH: Three Perfect Days: Houston

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1IydN76PjM

Day 1

Exploring Chinatown with a famous chef

Houston is a place of many surprises, the first of which is that the humidity will go right ahead and do your hair for you. By the time I finish drinking coffee on my charming little opera balcony at Hotel ZaZa, which overlooks the city’s live oak–lined Museum District, the bayou breeze has worked its magic, leaving my hair with more body than I thought possible. As far as hotel amenities go, I’m all for it.

My first stop this morning is a funky red-brick coffee shop called Blacksmith, for a croissant with crème fraîche and marmalade. I’m also meeting Chris Shepherd, who won the James Beard Best Chef Southwest award in 2014 and runs an ever-shifting restaurant empire on a few blocks of Houston’s Montrose neighborhood.

Shepherd enters Blacksmith with so much hand-shaking and back-slapping that he might as well be the mayor. A big man with oversize opinions, he tends to say things like: “The Houston food scene needs to be about more than us. It needs to be about a city united.” Diners at his most famous restaurant, Underbelly, leave with a list of local restaurants, farms, grocery stores, and bars that Shepherd recommends they visit before they come back.

My lips have swollen up as if they’ve been stung by wasps, and I still can’t stop eating.

One of the restaurants Shepherd advocates for is Crawfish & Noodles, a Vietnamese-Cajun joint in Chinatown that was recently featured (along with Shepherd) in David Chang’s Netflix documentary series, Ugly Delicious. Shepherd is taking me there to meet chef Trong Nguyen, a Vietnamese immigrant (the Houston metro area has the third-largest population of Vietnamese in the U.S.) who is making some of the most exciting food in the country right now.

At a no-frills table in the back, Shepherd orders us a round of Tsingtao beers, sticky-sweet fish sauce chicken wings, fried salt and pepper blue crabs that we crack open to mine the sweet lump meat, and tender turkey neck with shallots fried so thin and chewy you could mistake them for noodles. Then there are the spicy garlic-butter crawfish, served in a bag that you have to cut open so they tumble out into a bowl alongside a potato or two and a fearsomely spice-slathered cut of corn cob. We rip the tails off and suck the heads in rapturous silence for a few minutes, until we’re huffing and sniffling from the pepper. My lips have swollen up as if they’ve been stung by wasps, and I still can’t stop eating.

“Who’s got the stones to eat the corn?” Shepherd says with a laugh.

After lunch, he takes me on a tour of the neighborhood, stopping at a shop around the corner, Gio Lua Duc Huong, to pick up what he says is the best Vietnamese bologna in the city. Then he drops me back at Blacksmith, promising to meet up for drinks later.

To make room for dinner, I take a walk through Montrose, wandering streets lined with bars and restaurants and then rows of single-family houses whose porches are festooned with lanterns and whose pickup trucks sit beneath light-laced trees. Blame the weather: Houstonians love a good outdoor space.

About 15 minutes south of Blacksmith I find the Rothko Chapel, a nondenominational reflection space that Houston philanthropists Dominique and John de Menil commissioned from painter Mark Rothko back in 1964. (It opened in 1971.) Inside, benches and meditation pillows face 14 moody Rothko paintings, their brushstrokes uneven enough to suggest hidden realms receding into the distance, like when you put two mirrors across from each other. My favorite is a bluish one that looks like the nitrogen bubbles sinking into a Guinness. I mean, it’s also just a plain blue square, of course. Rothkos are confusing.

After freshening up at the hotel, I head back to Montrose for dinner at Shepherd’s Underbelly. Come July, the space that currently houses the restaurant will have been transformed into his latest venture, a steakhouse called Georgia James, while a smaller, nimbler version of Underbelly, UB Preserv, will have opened down the street, and Shepherd’s One Fifth concept restaurant, which offers a new cuisine every year, will switch to Mediterranean. Confused? All you really need to remember is that Underbelly’s signature dishes—Korean braised goat and dumplings, cha ca–style fish with turmeric and dill, and crispy market vegetables with caramelized fish sauce, which were inspired by Vietnamese wings like the ones at Crawfish & Noodles—will be available in perpetuity at Shepherd’s hipster craft beer bar, Hay Merchant.

After I’ve eaten, Shepherd returns to join me for a drink at the nearby Anvil Bar & Refuge, a classic cocktail bar with a good-looking clientele, huge windows, and a flea-market Campari sign so cool I’d try to steal it if I could figure out how to get it in the car. Apparently, new bartenders at Anvil have to spend a night making every drink on the house list of 100 cocktails you should have once in your life, and selling them for just $1 apiece.

Blame the weather: Houstonians love a good outdoor space.

Tonight’s bartender tells us there are going to be two of them tomorrow, which feels a little bit like that classic bar sign, “Free beer yesterday.” No matter—I’ll gladly pay full price for a cocktail as fun as the Weather Top, which arrives in a tiny coupe glass with a powdered sugar–covered rosemary sprig on top, like Christmas in spring.

Montrose is an ideal neighborhood for carousing—you can walk from bar to bar, and everyone seems to have the same starry-eyed idea about what nighttime is for. Shepherd and I have drinks. And then more drinks. “I can’t believe we’re opening three restaurants at the same time, and renovating our house,” he says. He claps me on the back, a sign that I have been approved by the de facto mayor of Houston. “We’re stupid,” he says.

Eventually, I say goodnight and call an Uber to take me back to Hotel ZaZa, where I shout “Goodnight, shiny horse!” to the disco-ball equine standing astride the lobby koi pond, and then crawl, fully clothed, into bed.

Day 2

Getting to the root of “Houston, we have a problem”

OK, I need a donut. Actually, I heard rumors last night about something even better: kolaches, savory stuffed buns that are like a cross between a ham croissant and a King’s Hawaiian roll, but with sausage. I decide to get one at Christy’s Donuts & Kolaches, a no-nonsense pseudo-diner in Montrose. Under an enormous yellow sign, a few hardcore patrons read the newspaper, powdered sugar on their faces. I order two kolaches: a standard sausage, cheddar, and jalapeño, and a slightly larger one stuffed with boudin—crumbly, heavily spiced Cajun rice sausage. The latter can only be described as revelatory.

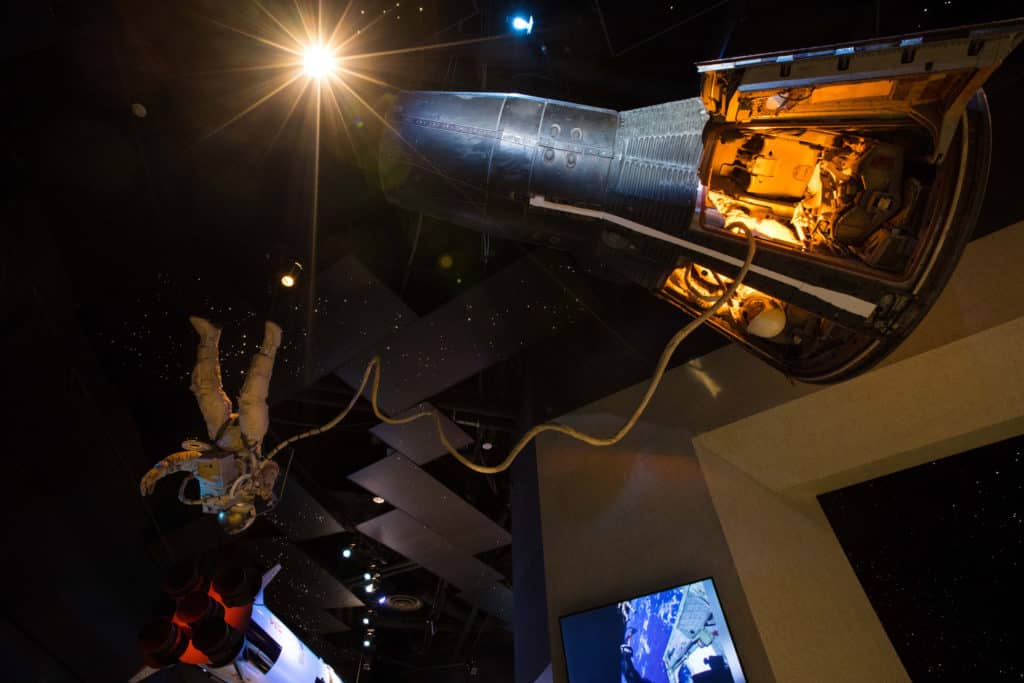

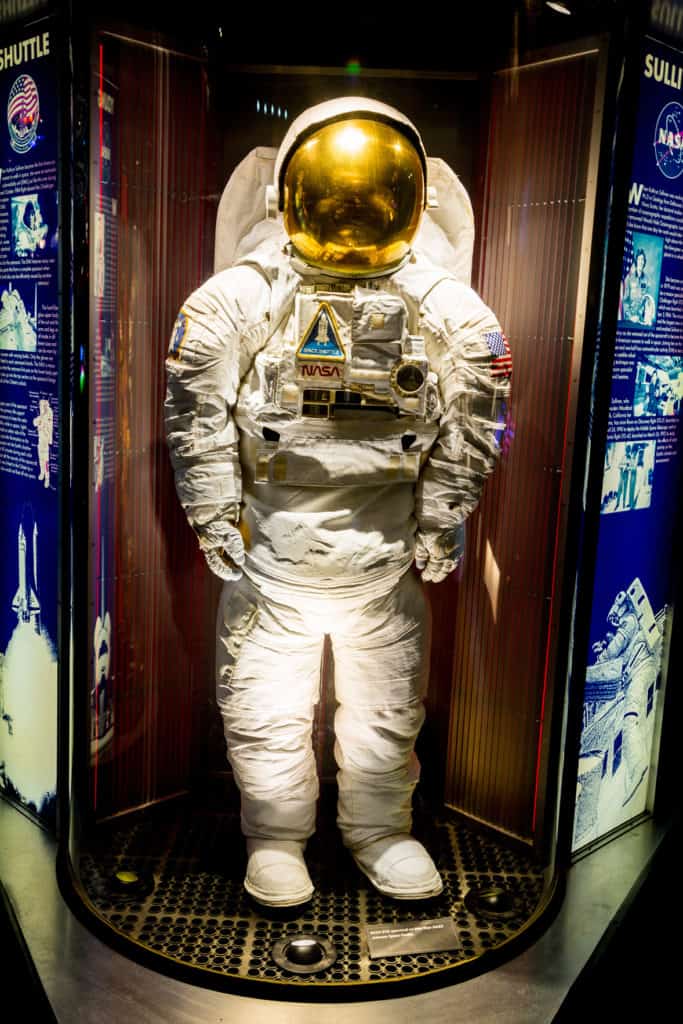

Next, I’m off on a 40-minute drive down to Space Center Houston, the only way you can get into NASA’s Johnson Space Center without a chaperone or a government ID. Inside the museum, I turn into an excitable 10-year-old. I touch rocks from the moon and Mars and pretend I’m a superhero. I climb into a replica space shuttle—the Independence—and pretend to press all the buttons. I look at old spacesuits and buy astronaut ice cream and imagine being crammed into the minuscule Mercury 9 spacecraft (about which astronaut John Glenn once said, “You don’t climb into the Mercury spacecraft; you put it on.”)

Finally, I board a tram for a tour of the actual Johnson Space Center. The first stop is the historic Mission Control Center, which handled the Gemini and Apollo missions (Remember “Houston, we have a problem”?) until it was decommissioned in favor of a modern mission control center in 1995. The man who leads our tour reverently describes the dedication of the team that put humans on the moon using less computer memory than you could stash on a USB stick. It’s sobering to learn a fact like that while looking at a room that could be a set in a 1960s period piece. What the heck have I done with all the power in my iPhone?

Next, we pass through the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility, where engineers are building a humanoid robot that is so dexterous it can turn a page without ripping it. A young boy leans over to his friend and says what I’m pretty sure everyone else is thinking: “I wish I had a LEGO set of this whole place!”

I turn into a 10-year-old, touching rocks from the moon and pretending I’m a superhero.

By the time I leave, I’m starving. Luckily, even from the highway it’s impossible to miss the massive wood pavilion that marks Killen’s Barbecue. The food here is so good—woody and smoky and wonderfully fattening—that there’s a long line of folks waiting to get in. I order tender brisket, smoky pork ribs, tangy collard greens, beef ribs, and mac ’n’ cheese so thick and gooey it’s practically a solid block.

There’s not much one can do after such a lunch, other than fall into a food coma or take a walk. I opt for the latter. Founded in 1986, Buffalo Bayou Park gives visitors a sense of what Houston was like before it was covered in cool restaurants and fancy offices. Surrounding a creek that flows from Katy, Texas, through the River Oaks neighborhood, and down to Galveston Bay, the park is a wild mix of Texas prairie flora, a haunting cistern that dates to 1926, a “lost” pond, and some unexpected wildlife.

The sun is setting when I enter the park, and I soon find myself waiting in a crowd next to a bridge, in the hope that the 250,000 members of the Waugh Drive Bat Colony will wake up and flitter out into the dusk in search of insects. Finally, they emerge, spiraling out in wispy curlicues. A hawk swoops by, trying to catch one, and the crowd makes disappointed “awww” noises when it misses, as if we’re watching a football game. But then the hawk succeeds, and tears its prey to smithereens in a tree while everyone watches in horror and fascination. What is this, Yellowstone?

Buffalo Bayou Park gives visitors a sense of what Houston was like before it was covered in cool restaurants and fancy offices.

Bats observed, I drive over to the Marriott Marquis, which towers over the downtown neighborhood of Avenida Houston like a Las Vegas casino. The marble lobby features intersecting arcs of grand chandeliers and fresh floral arrangements. From my corner room, which has almost more windows than walls, I look out onto Discovery Green, a park that hosts concerts and Saturday morning yoga and skating sessions in one of those plastic rinks that are ubiquitous in places with hot climates. I even have a view of the hotel’s 530-foot-long neon-blue lazy river, shaped like the state of Texas.

Tonight’s dinner is at the Marriott’s restaurant, Xochi, an ode to Oaxacan food from Houston chef Hugo Ortega, who won the 2017 James Beard Award for Best Chef Southwest. Ortega grew up in Mexico City, learned to make masa while living on top of a mountain with his grandmother, and worked his way up in the restaurant world starting as a dishwasher. If all that doesn’t establish this place’s authenticity, the seven-piece mariachi band that’s serenading an adorable Latina toddler when I walk in ought to do the trick.

I start with a mezcal old fashioned that’s so smooth you forget it’s mezcal—more like an expensive bourbon that decided to wear a cool hat. Then come the moles, four of them, ranging from a black one that takes two days to cook to a red one made with ants. These are followed by housemade queso fresco served with dollops of black bean and butternut puree, crispy gusanos (worms), and big, round ants, which taste like meaty Rice Krispies. Next comes an order of buttery baked oysters topped with yellow mole and roasted lime, which tastes so good I toy with the idea of moving to Mexico. Dessert is chocolate mousse topped with a chocolate branch with real leaves and flowers, washed down with a rich, creamy hot cocoa frothed tableside with a stick.

Do I go to sleep after this feast? Do you have any idea how much caffeine is in fresh hot cocoa? Near the Texas-shaped lazy river is an alluring rectangular fire pit. I grab my book and read a few chapters in the glow of the flames. When the crickets head off to bed, so do I.

Then come the moles, ranging from a black mole that takes two days to cook to a red one made with ants.

Day 3

Two-stepping from honky-tonk to the Heights

From my window, I can see a family playing in the lazy river, and given that I am still full from last night’s dinner, I decide to join them, lolling around in the pool like a sea lion until I get hot and retreat inside. The sun! Where have you been all my life?

Sun makes me hungry, so I drive back to Montrose to hit up Goodnight Charlie’s, which has just opened up shop for its Sunday High Noon brunch. The place is a hip Texas honky-tonk, and if that sounds like an oxymoron, it’s only because so is one of its owners: David Keck, a former opera singer from Vermont who attended Columbia University and Juilliard and came up with the idea to open this place while studying for his Master Sommelier exam. (He’s the 149th person in the U.S. to achieve the distinction.) “I’m kind of an obsessive person,” Keck tells me as I sit down to eat. (You don’t say.) “But country music and bourbon are two things that I feel no obligation to go down the rabbit hole about. I can just enjoy them. So there’s something about Goodnight Charlie’s that is just about having fun.”

He’s right about the fun: The stage is lit by pink and green neon cactus sculptures and a sheet-metal moon with punched-out stars. Behind the bar is a display that includes a 1970s Dolly Parton doll and a taxidermied armadillo holding a Topo Chico mineral water. I order breakfast tacos with chorizo, Yucatan-inspired cochinita pibil tacos with braised pork, and Mexico City–style cheese-steak tacos.

“There’s something about Goodnight Charlie’s that is just about having fun.”

From here, I drive up to the mellow, tree-lined Heights neighborhood to shop for souvenirs. At the top of some rickety wooden stairs I find Manready Mercantile, a pseudo–hunting lodge that sells flags and shirts and waxed canvas bags and man-scented candles made downstairs. I buy my boyfriend some bourbon-flavored toothpicks and myself a rose-and-musk candle from the $20 bargain bin. “They’re working on a new scent, and these are the ones that aren’t ready yet,” the saleswoman tells me. I sniff. Smells ready to me.

Down the street, I poke my head into AG Antiques, where, inspired by Hotel ZaZa’s disco horse, I gaze longingly at a 4-foot rose-quartz cow skull. I’m pretty sure it won’t fit into my carry-on, so I leave it where it is and hope someone reading a major airline magazine will buy it and give it a good home. Just don’t tell me about it, or I’ll be jealous.

At last, it’s time to eat some vegetables, and there is a perfect place for such an activity just down the street. Coltivare reminds me of a rustic Southern wedding reception: Globe lights are strung up across the backyard, which features a woodpile and happy people sitting in circles sipping rosé. There aren’t many tables available, but I manage to score a seat in front of the open kitchen, where I can watch the cooks artfully arrange pizzas in a blazing oven. I order buttery bread with chicken liver mousse and a crisp fennel salad with avocado and local citrus, followed by a large bowl of cacio e pepe with tons of Parmesan and olive oil. Olives are a vegetable, right?

Imagine Houston as a kid who went off to graduate school for mechanical engineering and still refuses to take off his cowboy boots.

To balance out this brush with healthy living, I head out in search of the diviest dive bar in town. I end up at Alice’s Tall Texan, which, seated at the intersection of two drab streets, is the kind of place where you’d get an establishing shot of a movie villain as he drives up. Inside, a couple of old-timers tap their feet to an even older jukebox. “What’ll it be?” asks the bartender, gesturing to the two taps, both of them Texas-born beers: Lone Star and Shiner. I choose Lone Star, and the bartender delivers it in a frosted chalice the size of my face. I have to use two hands to lift it. “That’ll be three dollars,” she says. Well, shoot.

I sit there and drink my mammoth three-dollar beer and watch some basketball and marvel at the idea that a place like this could exist down the street from a place like Coltivare. But the wonderful thing about Houston is that you wouldn’t even think to question it. The hip and the traditional, the country and the city, the immigrant and the old-timer—they’re all equally Houstonian, and sometimes they’re all the very same restaurant. Imagine Houston as a kid who went off to graduate school for mechanical engineering but still refuses to take off his cowboy boots. Who wouldn’t love a kid like that?

Up Next: Three Perfect Days in London