Montana has a knack for broadcasting its majesty. Almost anyone can picture the snowcapped Rocky Mountains sweeping down to cold, freestone rivers in the valleys below, crowned by that iconic big sky. Such beauty is hard to hide.

But it’s the blend of people and place that make this state truly special. Those who live here are passionate, resourceful types bound together by the severity of the seasons and a shared love of the land. They don’t take a day for granted, and they know life’s greatest treasures are free—and usually found outside.

Day 1

Sipping espresso with a pop star and watching surfers ride the river in Missoula

I’m standing 620 feet above Missoula, beside a giant white “M” branded onto a mountainside. Fifteen thousand years ago, I’d have been underwater. During the last ice age, a glacier dammed the Clark Fork River, creating a lake that was 2,000 feet deep and larger than Delaware. Beavers the size of grizzlies roamed its banks. Then the dam broke and flushed the lake out to the Pacific. The aftermath includes this midsize college town, where I now live.

The sun hasn’t quite crested Mount Sentinel behind me, but it’s light enough to see the maple-lined streets and the Clark Fork unspooling through town. Somewhere to my right, in the shadow of Mount Jumbo, is my house. It feels good to linger in the cool air and listen to the meadow- larks, but few moments are as heavy with possibility as a Montana summer sunrise. So when the University of Montana clock tower chimes the hour, I’m already jogging down the switchbacks toward another kind of pick-me-up.

I find it at Drum Coffee, a southside café owned by John Wicks, the drummer for the indie-pop band Fitz and the Tantrums. Wicks’s wife, Jenna, grew up in Missoula, and after the couple had kids they moved here from Southern California. Wicks is tall, with thick-framed glasses and a peacoat with notebooks in the breast pocket. Over a café cortado, he tells me that before he moved here he felt jaded, toiling away in a cutthroat industry. “The topography of this place plays a part in the humility here,” he says. “These mountains don’t care what you do. They’re going to be here when you’re gone. That plays a big part in people’s priorities.”

One of my current priorities is brunch at The Catalyst, a humming breakfast spot on a sunny downtown street corner. I take a seat at a table on the sidewalk and order a heaping plate of chilaquiles smothered in housemade tomato-lime broth. Missoula is coming to life now, and the morning twinkles with youthful potential.

From here, I walk to Caras Park to watch surfers in black wet suits playing in a standing wave on the Clark Fork River. The river is high and brown, but the surfers are game anyway, paddling like penguins into the froth, then springing to their feet, suspended on the roaring current. I feel a vicarious thrill. The thing I’m most looking forward to over these next three days is the driving, which I’ve arranged to do in a 1986 Volkswagen Westfalia Weekender Camper (a dream of mine). I collect one at the airport from Dragonflyvans, where Scott Quinnett introduces me to a van he calls Lizard King—both for Jim Morrison and for the lizard that was living in the engine when he bought it. The vehicle has a beige interior, the aerodynamics of a brick, and no power steering. I’m smitten.

Quinnett walks me through Lizard King’s particularities (take hills slowly) and hands me the keys. “I can almost guarantee you a blast,” he says with a smile. The van purrs to life, and I crank its large steering wheel homeward to pick up my wife, Hilly, a fourth-generation Montanan, and our sons, Julian and Theo.

Everyone piles in, and we head to Wally & Buck, a burger joint that began as a trailer in a brewery parking lot and grew into a hopping restaurant. We order a bag of burgers— including the daily special, a local grass-fed patty topped with pineapple, jalapeño, and sweet-onion mayonnaise— and a plate of lemon-zest parmesan fries. It’s ample fuel for us to roll out of town, through a notch in the hills on Highway 93.

Scarcely 40 minutes up the road is another must-stop: the Windmill Village Bakery on the Flathead Indian Reservation, where owner Nancy Martin sells fresh doughnuts made the same way her mother used to. She chops one up for Theo and hands me anotheron a square of wax paper. It’s warm, soft as a marshmallow, and gone in a few savage bites.

Along with the doughnut, Martin, who was born and raised in Montana, passes along a bit of perspective. “When you live somewhere else, people don’t like you until you give them a reason to,” she says. “In Montana, people like you until you give them a reason not to. And you can’t beat the scenery. The day we crest that hill and don’t gasp, we need to reboot, because something’s off the rails.” She’s referring to Ravalli Hill, and when we crest it, minutes later, we do gasp, as always. The Mission Mountains rise straight from the valley floor here, a blue-green wall of peaks that’s distractingly beautiful.

We drive beneath them to Polson, a sleepy town on the southern shore of Flathead Lake, the largest freshwater lake in the West and one of the cleanest in the country. We travel up the east shore, past cherry orchards, to Flathead Lake Brewing Co., in the artsy town of Bigfork. A frosty Two Rivers Pale Ale—named for the Swan and Flathead Rivers, which flow into the lake—wets my whistle after a day behind the wheel, and once we’ve worked our way through plates of shredded pork tacos and elk bratwurst, we’re all feeling sleepy.

Happily, our lodgings are close by—the campground in Wayfarers State Park beckons. We pull into the site, and I pop the top of Lizard King while Hilly builds a fire. We can see blue water through the trees below us. The campground is quiet.

At 10 p.m., it’s still light. Theo crawls into the upper bunk; Hilly, Julian, and I stretch out below. I go to sleep thinking there’s no place I’d rather be.

Day 2

Drinking huckleberry milkshakes and cycling in Glacier National Park

OK, the night wasn’t total bliss. After midnight, Hilly elbowed me awake to say, “You’re doing that breathing thing again.” The kids were restless. But by 6:30 the birds are singing, and I’m rested enough to slide open the van door on a new dawn.

Lizard King makes camping almost effortless. I pull a propane burner from the cup- board, along with a kettle and a French press. Minutes later, I hand Hilly a cup of coffee; Theo and Julian supervise as I fry eggs and sausages over the campfire.

After breakfast, we walk down to the lake, which is lined with moss-green rocks and clumps of purple flowers. The sun is warm, and I decide to take a dip. It’s a brief one. This lake used to be a glacier, and it hasn’t heated up much since.

It occurs to me a boat ride would be a much warmer way to take in the lake. Fortunately, Amy Grout, the Flathead Lake State Park manager, has offered to take me out to Wild Horse Island, a 2,163-acre park and the largest island in the lake. The Salish and Kootenai tribes used to swim their best horses out to the island to foil thieves, and it’s still home to five wild horses, plus about 100 bighorn sheep, 50 mule deer, a handful of coyotes, a black bear, and a mountain lion.

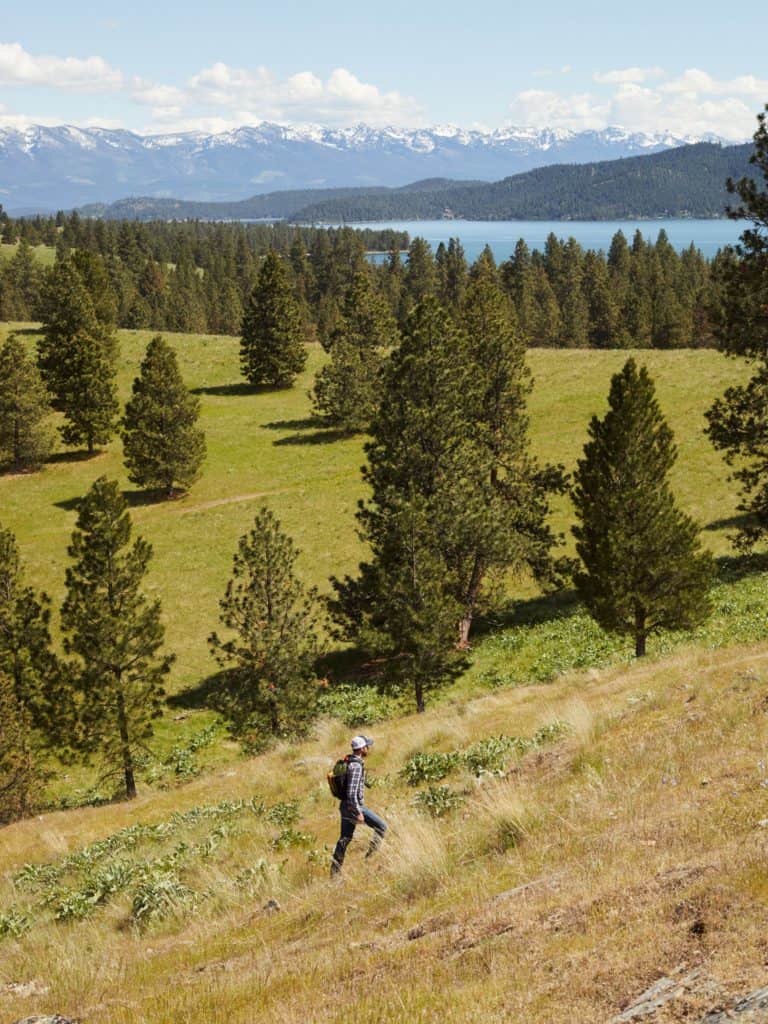

While my family plays on the shore, I wobble aboard Grout’s motorboat and fasten my life vest. Grout steers away from the dock and points the bow toward Wild Horse. “This is a little gem of Montana,” she says. “It’s a pretty special place.” Waves slap against the aluminum hull, and after overcoming some engine trouble, we make landfall. I follow Grout up the hillside, wading through a knee-deep sea of bright yellow arrowleaf balsamroot, past a century-old homestead and a feral apple orchard. The trail is redolent of horse dung, but we don’t see the horses. Grout does, however, spot a giant bighorn sheep through her binoculars on a ridge above us. “That’s a world-class ram,” she says. Four others filter out of the trees around it.

We finally drop back down to the shore through a glade of old ponderosas that smell of butterscotch. “This is where I was meant to be,” Grout says. “I love the landscape and the people. Montanans, we’re hardy. We’ll do anything to help someone out. We can be very stubborn, but we love the place we live.”

Back on the mainland, I rejoin Hilly and the boys to continue northward, past the strip malls of Kalispell and the lumber mill in Columbia Falls. In the town of Hungry Horse (population 518), we pull over at Willows’ HuckLand, a roadside gift shop that’s said to serve the area’s best huckleberry milkshake.

We find the owner, Buddy Willows, behind the counter inside, eating a buffalo burger. He’s surrounded by shelves of huckleberry everything— honey, syrup, jam, barbecue sauce. “We only use Montana huckleberries,” he tells me. “I’d say they have about 15 to 20 percent more twang.” He hands me a copy of his self-published autobiography, The Wild & Crazy Buddy Willows. It’s not at all a dull read.

We leave with a lunch of huckleberry shakes and huckleberry pie (don’t judge) and drive 10 miles to the entrance of Glacier National Park, where we all go quiet at the view of the peaks rising behind Lake McDonald. Two mule deer cross the road in front of us. Soon, we’re checking in at the Lake McDonald Lodge, a chalet on the north shore that was built as a hunting lodge in 1913. The lobby has a stone fireplace, cedar beams, and animal heads mounted on the walls. Lampshades decorated with Native American pictographs hang from the ceiling. Outside, a colony of ground squirrels scurries and chirps. “People call them whistle pigs,” a lodge employee tells me. “They own the property. We don’t.”

It’s time to leave the family again, as I’m not sure the kids would enjoy my next adventure: a steep bike climb up the Going-to-the-Sun Road. The road doesn’t open to vehicles until winter’s 80-foot snow drifts are fully cleared, which usually happens sometime around midsummer. Before then, it’s one of Montana’s most scenic cycle rides.

I start off on a bike borrowed from Glacier Guides, quickly gaining elevation as I follow McDonald Creek upstream. The water is an otherworldly shade of blue thanks to the glacial silt it carries downstream. I pass two piles of bear scat on the road. I don’t see any bears, but I do see plenty of delicate white trillium flowers. They look like fallen stars.

I’m surrounded by mountains, some of them giant domes of snow, others sheer rock faces that fall from their ridgelines like the cheek of an ax. I stop at Haystack Creek, a tranquil spot a few miles from the pass. Looking around at what the Blackfeet call the Backbone of the World, it’s hard not to feel a bit sad. In the mid-1800s, there were about 150 glaciers here. Now there are 26. Some scientists project that within 10 years they will all be gone.

At the end of my ride, I return to the lodge to meet Hilly and the boys, who spent the day walking the Trail of the Cedars. With a broad view of shimmering Lake McDonald, we dine on smoked Columbia River steelhead and local pork shank with buttery mashed potatoes. I wash mine down with a Going to the Sun IPA, brewed in nearby Whitefish.

As a woman plays “Edelweiss” on the lodge piano, Theo passes out over his fruit plate. Hilly carries him to bed while the wind ruffles the lake outside.

Summer is glorious in Montana, but locals know it’s fleeting. Winter, on the other hand, endures, and there’s no better way to come to terms with it than on a pair of skis at Big Sky Resort. The second-largest ski resort on the continent, after Canada’s Whistler Blackcomb, Big Sky boasts nearly 6,000 uncrowded, skiable acres, including triple-black-diamond runs that will make you sweat and then sing. Fast, big new chairlifts put all of the terrain within reach.

Big Sky has also undergone a recent overhaul of its après scene. The Exchange, in Mountain Village, now hosts a modern food hall with ramen and wood-fired pizza. Westward Social is a new bar with craft cocktails and friendly drinking games. Catch live music at Montana Jack, and enjoy high-altitude fine dining at Everett’s 8800. Lodging is more plentiful too, with Montage Big Sky set to open next winter. With all this, you may never want summer to come.

Day 3

Herding cattle, catching trout, and glamping on the Blackfoot River

After a huckleberry pancake breakfast, we decide there’s time for the five-mile hike to Avalanche Lake. The woman at the front desk tells us a grizzly sow and two cubs were on the trail recently, so we pack bear spray, although we soon learn that Theo melting down over a lollipop is probably a more effective deterrent.

The trail is well traveled. When I stop to take a picture of Theo in a hollowed-out tree, a lady walks by and says, “We have that same photo with our daughters, 20 years ago!”

At the lake, people nibble granola bars and gape at the enormous picture postcard in front of us. In the center of it all is a waterfall that begins at Sperry Glacier and crashes hundreds of feet down the mountain.

We have more driving to do. Back in Lizard King, we exit the park and follow the verdant Seeley Valley down to another, wider valley, where we find The Resort at Paws Up, a dude ranch on the Blackfoot River. The lodgings here are fit for a cattle baron—palatial homes featuring wrought iron, burnished wood, cowhide, and leather—but my family opts for a (relatively) more rustic experience. We’ll spend the night in a safari tent with electric blankets on the king- size bed and a heated floor in the attached bathroom. Two butlers meet us at the tent, though they look more like outdoor sportswear models than coat-and-tails types. One of them points out a bald eagle’s nest overhead.

My first activity is a cattle drive. In a wide meadow, I meet equestrian manager Jackie Kecskes, who’s resplendent in white leather chaps, with an elk-antler knife on her belt. She introduces me to my horse, a tall paint named Kid. We set off through the sagebrush with three other wranglers, and Kecskes talks me through the basics: A tap of the heels makes a horse walk; pulling the reins makes him stop; pressure on his right side makes him turn left, and vice versa. “You know the outcome you want to achieve,” she says, “but it has to be their idea, otherwise it won’t stick.” I recognize the tactics from parenting.

As we reach the cow pen, the animals look up, as if to say, “What, this again?” Kecskes swings open the gate, and I try to help the other wranglers herd the cows toward her. But I keep messing up my turn signals, applying pressure with the wrong foot. Kid is con- fused. Then he seems to accept my ineptitude and takes the lead. Evidently, he knows the outcome he wants to achieve.

After driving the cows to an open pasture, the wranglers teach me how to cut one from the herd, as real cowboys do. It’s a lot like parallel parking, except the curb keeps moving to join the other curbs, and my car has lost respect for me. I manage it once or twice, and then we herd the cows back to the pen. It’s not exactly Lonesome Dove, but I’ve got a little swagger as Kid charitably returns me to the stable.

We have some time before my next activity, so I watch the boys while Hilly gets a massage at Spa Town, a row of white tents on the forest’s edge that looks like a place a soldier might convalesce after a Civil War battle. Once she’s suitably relaxed, I head out for some fly-fishing. The Black- foot is running high with snowmelt, and I don’t expect great fishing, but my guide knows a few slower spots. He hands me a rod rigged with a large streamer and pushes off the raft.

My mind drifts as we float downstream, but suddenly there’s a tug on the line and the buttery swirl of a big brown trout. Slowly, I work it toward the boat. The guide slides his net underneath and lifts from the water one of the finest fish I’ve ever seen. It’s a golden slab of a trout, with black spots, a hooked jaw, and a reddish tail the size of my palm. I ease my hook from its mouth, and it swims power- fully away.

Our tent is a mile downstream, and I’ve worked up an appetite. My hunger is in good hands with chef Sunny Jin, who earned his chops at premier restaurants in Napa Valley, Spain, and Australia. As with many people, his presence here is a matter of the heart. “I came here on a fly-fishing road trip, and I absolutely fell in love with it,” he tells me. “I didn’t have an option at that point.”

I quickly learn that Jin is a sort of magical blend of wood nymph and master chef. He grew up foraging, and he spends his free time here scouring the property for ingredients. In spring, he hunts for morel mushrooms, digs for balsamroot, and chops down cattails, whose early shoots are a crunchy cross between a cucumber and a leek. In summer, the property has huckleberries, salsify, and hot pink fireweed for bitters. Jin calls it all “the edible wild tapestry,” adding, “It’s hard to starve here when you know where to look.”

Starve we do not, as we dig our forks into king salmon brûlée with candied kumquats, green garlic bisque with toasted almonds, and New York strip steaks (from the ranch’s cattle) with black mushroom ragout. For dessert, there’s citrus pavlova with pistachio sponge, fennel pollen crémeux, and meringue wafers that taste the way a cloud looks, bright and lazy in the summer sky.

After dinner, we repair to the fire to let our bones soak up its warmth and our minds marinate on the day’s adven- tures. Montana has been generous to us. We’ve pulled its treasures from the water, found them at the end of a mountain trail, and felt them in the tremor of the muscles on a horse’s neck. When we finally return to the tent and climb into our heated beds, there’s no need to set up a white noise machine for the kids—the dull murmur of the Blackfoot River lulls us into a deep, restful sleep.