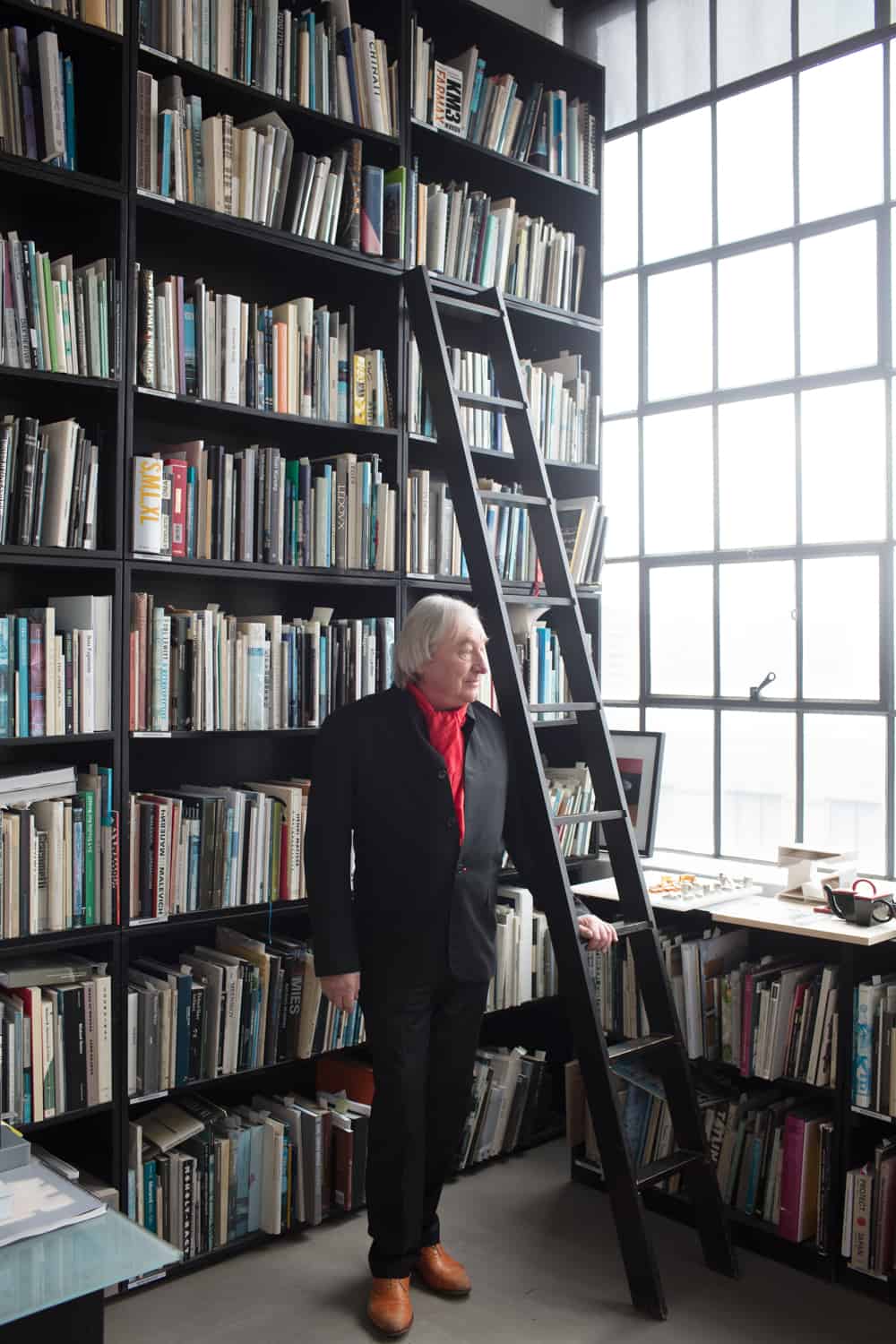

Steven Holl, in a way, is an archetypal 21st-century architect. He’s renowned for designing museums, academic facilities, and office complexes that look the way buildings do in dreams—compositions of unaccountable shapes that emerge from the ground at surprising intervals and glow like alien life-forms. But Holl, 70, who has the face of a cherub, framed by shaggy white hair, seems rooted in some other century; maybe not the past, exactly, but a very different version of the present.

“Every day, I get up at 10 to 7 and work for an hour on drawings,” Holl says. He does watercolors—sweet, amorphous, somewhat geometrical studies that are not obviously buildings. Whereas most of today’s architectural designs begin and end on a computer screen, Holl’s start out on paper. His drafting table, in his firm’s Manhattan office, faces a bulletin board covered with the little paintings, a few of which show a cluster of bookend-like thingamajigs perforated by Swiss-cheese holes, the basis for a new commission in Moscow. The project is a housing development on the site of a former airfield, and the holes are metaphorical parachutes drifting from the sky. “I just play around,” he says. “I’m very free with my thoughts.”

Holl has painted similarly ethereal watercolors for every building he’s designed, from early works like the Chapel of St. Ignatius on the Seattle University campus to his very latest, the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, a fabulously unruly arrangement of white polygons that opens this month. Ultimately, of course, the 36 architects who work for him (in New York and Beijing offices) will translate his loose concepts into detailed computer renderings and models. Holl, however, treasures the originals, many of which are in sketchbooks stored above his desk. “I have 30,000 watercolors,” he says. “I can find the first sketch of every project.”

Holl grew up in Bremerton, Washington, an hour by ferry from Seattle, which was, back then, a navy town. “There were no architects,” he recalls, just “big hammerhead cranes and aircraft carriers.” Holl and his brother Jim, now an artist, invented their own architecture, building a two-story treehouse and an underground clubhouse in the backyard. After graduating from the University of Washington, Holl won a fellowship that sent him to Rome, where he snuck into the Pantheon every morning, before it filled with tourists, and watched the sunlight move through the ancient temple.

[The key is how] a body moves through the spaces, how the sequences of spaces open up and close, how the natural light animates this body.

Although he was inspired by Classical Rome, Holl’s approach to architecture owes more to the Renaissance, when, he says, the discipline intermingled with other art forms. Music, for example, often provides the inspiration for Holl’s buildings. He based one early project, the 1991 Stretto House in Dallas, on a piece by Béla Bartók; the four movements of Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta became the four wings of the house. Recently, he based the colorful facade of London’s new Maggie’s Centre Barts, a facility that provides support for cancer patients, on a medieval system of musical notation.

Mainly, Holl is driven by the idea that architecture, like music, is an experiential medium. It’s not something you look at with your eyes, but that you sense with your whole self. The key thing, he argues, is how a “body moves through the spaces, how the sequences of spaces open up and close, how the natural light animates this body moving through space.”

Holl has many buildings you can visit to feel his spatial music. His museums, like the Kiasma in Helsinki and the Nelson-Atkins addition in Kansas City, are wonderfully immersive. Starting on April 21, you can visit the new ICA in Richmond and follow that up with a trip to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where the first phase of the new Holl-designed campus, including his Glassell School of Art, will debut on May 20. (Oh, and if you really want to take the plunge, you can book a weekend in one of his designs, the Ex of In House in Rhinebeck, New York, on Airbnb.)

The ICA’s interim director, Joseph Seipel, has already had the ultimate Holl moment in the complex’s triple-height top-floor gallery: “One of our visiting artists played his cello in there, and it slices right to your heart,” Seipel recalls. “The sound is so intense in that space.” The ICA will showcase a wide variety of contemporary art forms, so there might not always be a cellist on hand. But you don’t need a soundtrack to experience the music of Holl’s architecture. All you need is an unlocked door. As Holl puts it: “If you see some building of mine, please go in it. That’s where the heart is.”