At the opening of his new memoir, Putting the Rabbit in the Hat, Brian Cox really does go back to where it all began. “There was no abseiling down Fallopio and into the light for me,” he writes of his death-defying birth. “I was going in the other direction, my wee hands clasping at the funiculus umbilicalis, wrapping the cord around my neck.” So it goes for the following 350-odd pages, a catalog of tragedies and triumphs, confessions and actorly advice, often delivered in a similar sardonic tone.

The youngest of five children, Cox was born in Dundee, an industrial port city in eastern Scotland. His parents were affectionate, his extended family peppered with colorful eccentrics, his home life cramped but reasonably stable. Then, when he was 8 years old, his father died, his mother suffered a mental breakdown, and young Brian was given a crash course in emotional and financial deprivation. He recalls kicking his heels alongside the city’s River Tay, thinking, I’m gonna cross that b***** one day.

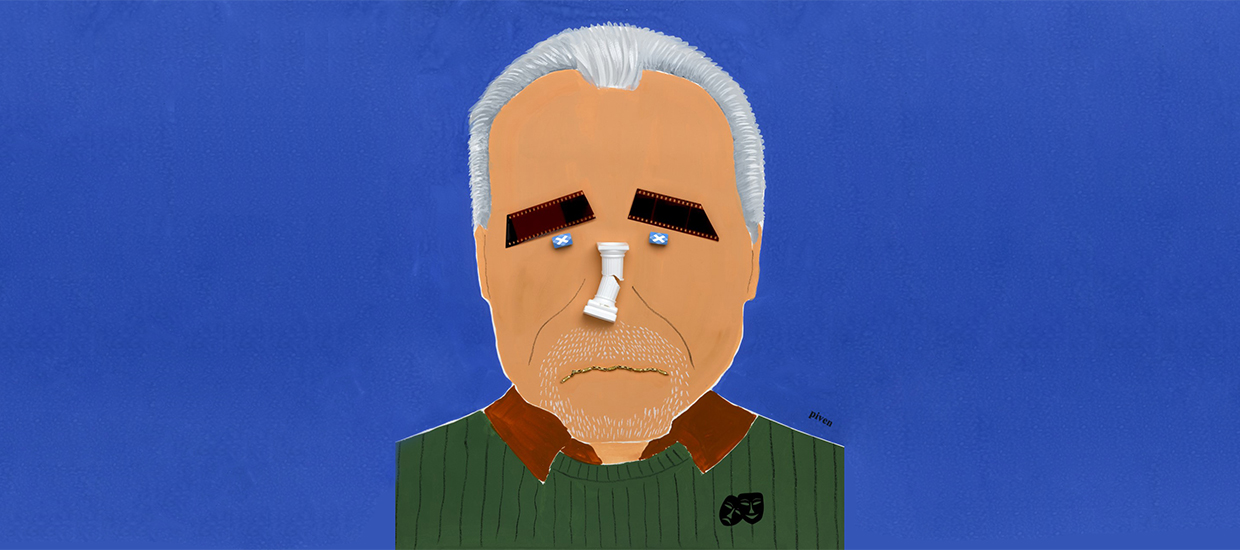

And cross it he did, going on to forge an acting career that has spanned more than five decades of television, theater, and film. A self-described “nomad,” Cox, 75, has worked with everyone from Laurence Olivier to Scarlett Johansson, his roles ranging from Titus Andronicus to Hannibal Lecter, with the only real constant being a tendency to play disagreeable, overbearing men. All of which, of course, has culminated in his turn as Logan Roy, the scheming family patriarch in the HBO hit Succession.

Cox spoke with Hemispheres from his home in New York, where he lives with his wife and two youngest sons—neither of whom, he assures us, is plotting to bring about his downfall.

Preparing for this interview, I came across a telling line on your IMDB profile: “Often plays cruel or immoral patriarchal figures.” Sound familiar?

Yes, I’ve played a lot of supposedly bad people. There have been times when I’ve got heartily sick of it. But then I suddenly realized that I’ve been put in a very privileged position. I teach drama, and I always say to students, “Try to picture yourself as a child and realize that it could have been you who became Adolf Hitler.”

Um…

The point is, humans take certain paths—whether to becoming an artist or a mass murderer—and we have to ask ourselves why and how they got there. This is what I love about my job: trying to make sense of people.

It’s a gift.

I was late getting into Succession—I wasn’t sure I wanted to watch a show about a bunch of spoiled rich people— but now I’m hooked. I don’t like these characters, but I enjoy them, and there’s a vulnerability there, so we see them as human rather than just monsters. You get drawn in.

Unquestionably, and credit for that goes to the writers. The mark of great dramatists is they don’t judge; they allow the characters to be. So what happens is that audiences, as they go through the process of not liking these people, begin to feel something else. Something shifts. You’re right, these people seem so unattractive—they deeply, deeply do—yet at the same time they are compelling and somehow sympathetic.

There’s still the question as to why they keep casting you in these roles. Is it something about you? In your memoir, you admit to having a prickly side.

Like everyone, I have elements of intolerance. I do play the occasional nice guy—I’m about to play a columnist who fights corruption—but much of the time they want me to play this contentious fellow. The fact is, there are a******s in the world, and a******s behave in a certain way. I don’t judge. I just say, “This is the guy, this is what he is,” and I guess I’m pretty good at it.

I wanted to ask you about the title of your book: Putting the Rabbit in the Hat. What does that mean?

The whole point of that is you can’t pull a rabbit out of a hat unless you get the rabbit in the hat in the first place. Meaning, you can’t create anything unless there’s something there to stoke that up.

Ah, I read it differently: You’ve pulled the rabbit out of the hat, but then you put it back in because there’s no magic left.

Oh, be logical, for Christ’s sake! Be logical! You’ve got to get the rabbit into the f****** hat before you can pull it out— never mind going in and putting it back! I mean, really, think about it.

But there’s no magic at all unless you pull the rabbit out.

Oh, f*** off! [Laughs.]

Watching you in Succession, there’s a sense that this is a role you were born to play, and your memoir reinforces that. As you point out, you share many characteristics with Logan: a sense of displacement, obstinate self-reliance, “a certain disgust with the rest of the human race.” And there’s so much about fraught parent-child relationships in the book.

The one thing I haven’t had a problem with is parents. I only have love and sympathy for them.

But both were missing in a way—your father died when you were young, and your mother had mental health issues.

Yeah, yeah, they were. What I mean is, I didn’t have anyone saying, “You should do this with your life, you should do that.” In a way, I was neglected. I got angry about this while I was writing the book: Why was no one taking care of me? My older sisters looked out for me, but they didn’t look after me, because they had families of their own. But you get on with it. I look at myself now, and I worry. I have a son who is 50 years old—my poor son has been stuck with me for 50 years. I feel bad for him.

You’re open about your own parental failings in the book. You missed your eldest son’s birth by a few minutes, you tell us, “which somehow set the template for my role as a father.” Again, it’s remarkable how the personal details dovetail with your on-screen character.

True, but you also have to remember that Logan Roy is a creation. I use what I know to make him feel alive, to present him as honestly as possible. That is an actor’s job—though a lot of actors are too busy trying to present themselves. They just get up and do their shtick.

In the book, you can be quite harsh in describing other actors. On Michael Caine, for instance: “Being an institution will always beat having range.” Or Johnny Depp: “So overblown, so overrated.” You’re already getting blowback for this. You must have anticipated that when you wrote these things.

No, I forgot about the consequences [laughs]. I can be too sharp for my own good sometimes. I’m writing an addendum to the paperback to make it clear that I don’t disrespect anyone in this profession. I may have reservations about their decisions, just as they may have reservations about mine. I also realize, well, if someone was an a****** 30 years ago, it doesn’t mean they’re an a****** now. Everyone is capable of change.

There’s a lot of humor in the book: you, as King Lear, hurling your crown and hitting some poor woman in the front row. Even the tragedy has a comedic element: your mother’s urn being dropped and people scrabbling around on hands and knees, picking bits of ashes out of the shag-pile carpet.

You have to be able to laugh. It’s part of the Celtic tradition, to be able to see how ludicrous you are, how ludicrous life is. As an actor, you come to realize that these masks of tragedy and comedy, the Greek notion of what theater is, disregards how absurd human existence can be. Once you embrace that idea, there is much more dramatic potential.

Yet in the book you wonder whether Succession’s writers don’t sometimes overplay the comedy at the expense of the drama—which, for me, is part of its brilliance.

Yeah, that was a passing thing. I don’t harp on that. This is a satire, and our writers do a fantastic job. My only question—and this was sophistry on my part, if you like—was whether there might be something else going on, something other than the taglines. But then, of course, they’re such brilliant lines.

You also write that drama should “touch on the inner life of people.” Do you think Succession has done this, tapping into a kind of collective psychological state?

That’s exactly what it does, and that’s why people are hooked on it. It’s reflecting our inner angst, the horrific idiocy and vanity of our leaders, our contradictory lives. We’re more lost than we ever have been. We have all this knowledge around us, all this technology, and we don’t know what to do with it.

You’re a self-described “semi-socialist.” You grew up facing money troubles. You’ve praised “kitchen sink” dramas for opening doors for working-class actors. Yet here you are playing a billionaire media baron, flying around in helicopters and sailing on luxury yachts. Do you see an irony here?

Absolutely. That’s the insanity of life. I mean, you just nailed it. It doesn’t make any sense.

But it must be fun, pretending to be a part of this world.

It’s actually a little overwhelming, especially the effect it has on audiences. We did a premiere of the show in London. The cast walked onstage and the reaction was extraordinary—people just went wild. Someone said to me afterwards, “Aren’t you a little long in the tooth to be the leader of a boy band?” And you’re feeding that frenzy while also thinking, What’s going on? The one thing I really miss is my anonymity. Before, the most that would happen is people might approach and say, “Hey, you’re, um… Didn’t you used to be in, ah…?” Now everyone knows who I am, and I’m not altogether happy about that.

Do you get a lot of fans coming up to you and asking to hear Logan Roy’s famous two-word catchphrase?

Yes, I get a lot of people asking me to tell them to f*** off. It’s a bit of a problem, because the one thing you want to say in these situations is, “F*** off.”

Next Up: Stanley Tucci Dishes on His New Memoir and the Complexities of “Red Sauce”