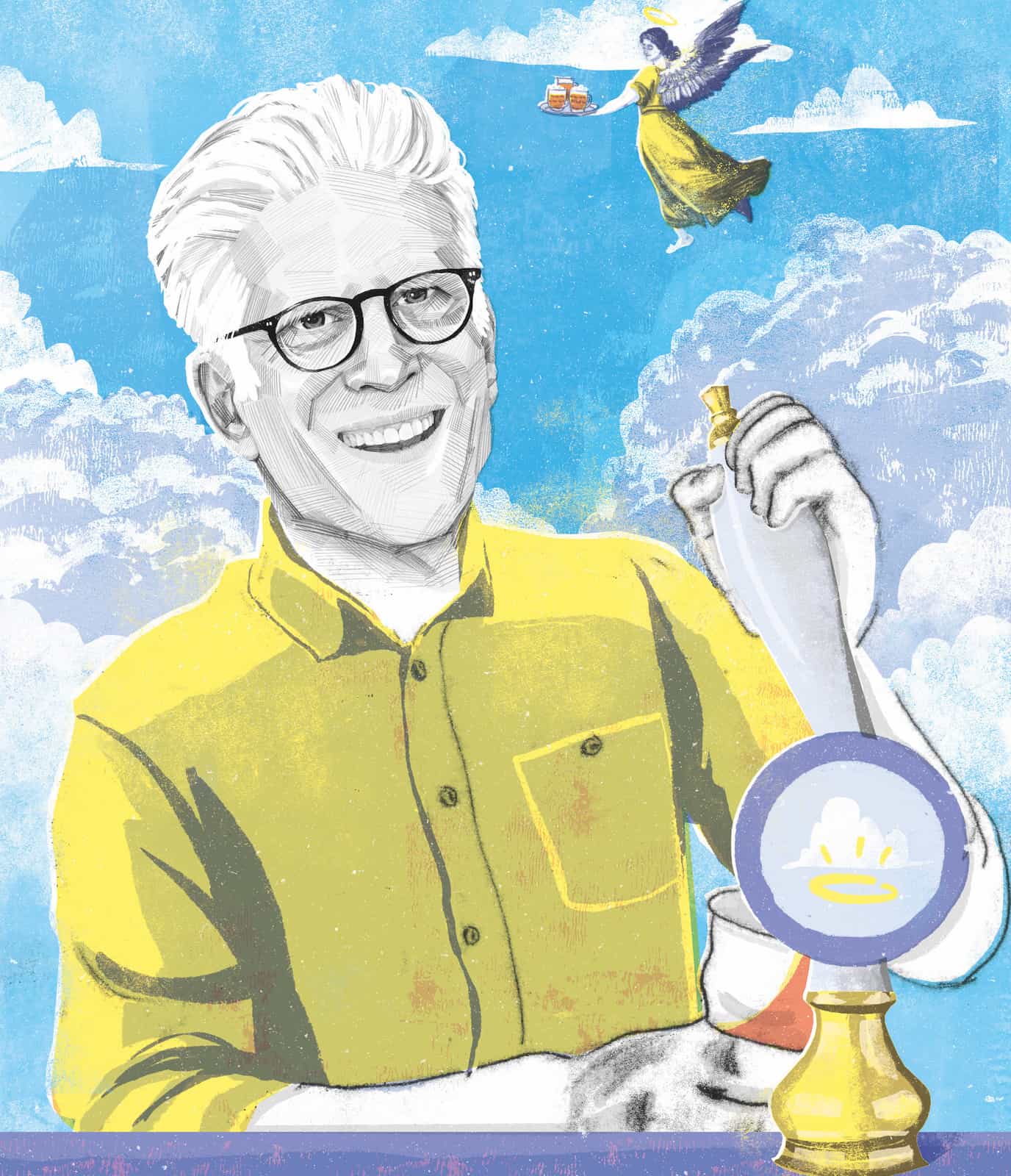

ILLUSTRATION BY LUKE WALLER

Ted Danson has always been charming. Anyone who watched the first scenes of Cheers, way back in 1982, could tell that. But it wasn’t yet apparent that the actor who played “magnificent pagan beast” Sam “Mayday” Malone would go on to become one of pop culture’s elder statesmen, his snow-white shock of hair and his sweetly romantic, later-in-life marriage to Mary Steenburgen lending him a buoyant gravitas.

Of course, it’s not just his private life that makes Danson an icon. It’s also his voracious appetite for new projects. Many stars with a role as memorable as his womanizing retired ballplayer in Cheers never hit the strike zone again. But since Cheers went off the air in 1993, Danson has embodied not one, not two, but a half dozen iconic TV characters: the mercurial eponymous physician in CBS’s Becker; evil billionaire Arthur Frobisher in Damages; dissolute magazine editor George Christopher in HBO’s Bored to Death; crime scene investigator D.B. Russell in two installments of the CSI franchise; sheriff Hank Larsson in the cult hit Fargo; and, perhaps most memorably, a loosely fictionalized version of himself in Curb Your Enthusiasm.

This month, the two-time Emmy winner returns to NBC, the network that launched his career, in the surreal heaven-set sitcom The Good Place, by Mike Schur, a writer-producer on The Office and co-creator of Parks and Recreation and Brooklyn Nine-Nine. Danson stars as afterlife architect Michael, a bow tie–wearing latter-day Clarence “Angel, Second Class” Odbody, who must guide the newly arrived—and newly deceased—Eleanor (Kristen Bell). The catch? She may have ended up in the “good” place by accident.

In conversation, Danson is generous, curious, and intellectually engaged—especially when it comes to saving the world’s oceans, a longtime passion project for the actor-activist. Here, the sitcom legend talks about his new project, how cable forced network TV to get better (and weirder), and how a son of a scientist who grew up in a dry desert state became enamored of the world’s watery places.

I was able to watch the first episode of The Good Place the other day, and it seemed so awesomely strange for network television. Were you familiar with showrunner Mike Schur before you were cast?

Well, indirectly, because I really loved Parks and Rec, and The Office was spectacular. He has this amazing pedigree. The first time I met him was in my manager’s office. He had been talking with Kristen Bell about this idea, and it sounded just so smart and so bright. It’s almost Alice in Wonderland–like in its wonderful, delightful insanity.

I really liked the peacock bow tie you wear in the first episode.

As an actor, you have the words. Then you try to figure out the character. And that’s a wonderfully collaborative art. Wardrobe, costume design, will come up with something that is just brilliant and unlocks this little box of imagination inside of yourself. Our costume designer came up with this bow tie and it was like, “Oh, thank you. Now I know who Michael is.”

It seems as if The Good Place, for Kristen Bell’s character at least, is kind of a fish-out-of-water story. And your character is also adjusting to a new situation. Are you an angel? Can old angels learn new tricks?

Michael is the architect of this particular neighborhood in heaven. Literally every blade of grass has been designed by him. It has been set up and designed for 322 people exactly. Things go awry on the very first day of this new batch of souls coming into the afterlife. It’s about everyone kind of coping with that.

It’s such a weird premise, and it goes to show the kind of crazy things you can do on TV these days. TV used to get a bad rap. Now I think you could argue that TV is better than movies. Why do you think that is?

I think cable changed everything. You could create shows for a very specific niche. And binge-watching: People are now enjoying sitting down and watching whatever they want to watch, at their own pace. All of a sudden, you have shows that are 10 episodes long, 10 hours for a writer and a director to tell a story, which is more than you get even for features. So you start to attract writers who want to experiment in this area. And if you get really great writers, then you get really wonderful actors and directors, and you stand a better chance of making something authentic and interesting for the audience. I think networks are beginning to catch on to that. My wife, Mary Steenburgen, is on a show on Fox called The Last Man on Earth, and they’ve broken the mold for network TV comedies.

More and more shows, The Good Place being one of them, are moving to these shorter, 13- to 16-episode runs per season. Do you think that’s kind of a sweet spot?

It works for us actors, because then you can go off and do other stuff as well. Mike has expressed the thought that you’re able to create an arc with 16 episodes that doesn’t repeat itself, that’s original, and each show builds on the other ones. But if you have to do 22 episodes, four or five or six are just kind of vamping.

Schur wants The Good Place to confront big issues of morality, goodness, and evil. Do you think sitcoms are set up to deal with these big things that touch people’s lives?

I do. I think your first mandate is to be funny—it is a comedy. But look at All in the Family; it certainly did that. We’re really about what it means to be a good person or a bad person, to do good things or bad things, and that they have consequences, and that there are ripples that go out from everybody’s actions. Everything counts.

That reminds me of the way people felt connected to the characters in Cheers and the events in their lives. Someone said that when Sam Malone came in drunk at the start of season three, then you had a saga. Despite that, does being remembered for your role on Cheers ever get old?

No, dear lord. I got to work with some of the greats: Les and Glen Charles, Jimmy Burrows, and all the other writers they attracted who came out of that Mary Tyler Moore tradition of writing. And then I got to work with these astounding actors. It was just flat-out fun for 11 years. But also, the fact that you and I are talking comes from Cheers. Everything, really, comes from Cheers. So I am forever grateful, and I get it.

Do you have actor friends who also played iconic characters?

Sure. Henry Winkler was about as iconic a character—the Fonz—as you can imagine. I’m very close friends with John Krasinski [who played Jim Halpert in The Office]. What he created was astounding.

Do actors feel good about that? Or is it a heavy mantle to wear?

It’s a wonderful problem to have. I think it’s your job as an actor to take risks and do other things. Some people may not like that; some people want to hold you as they remembered you. I’ve bumped into that periodically. But if you look for really great writing, really original thinkers, and ask very nicely if you can be part of that, no matter how big the part is, you will end up branching away from an iconic character. Follow the writing and you stand a chance of doing something new and different and authentic.

You’ve done some writing yourself, including a book about ocean conservation, Oceana, with journalist Michael D’Orso. How did you find the writing process?

Horrifying! I was working with a really wonderful writer, and most of the information and science came from Oceana [the world’s largest ocean conservation and advocacy group], so my contribution was more about, “This is who I’ve been spending time with, this is what they’re saying about this issue.” It turned out really, really well, and I’m glad I did it, but…

You’re not going to become a novelist anytime soon.

[Laughs.] No. The writing and reading world can rest assured. I’m not coming your way.

Follow the writing and you stand a chance of doing something new and different and authentic.

You grew up in Flagstaff, Arizona. How did you first get interested in the oceans and sea life?

Well, my father was an archaeologist, an anthropologist. So I was surrounded by scientists growing up. None of it sunk in, but there was this sense of stewardship. So I think I had that in the back of my head. Then we would go visit my cousins, all jumping in a couple cars and driving to La Jolla, Laguna, Del Mar, that area of Southern California. We’d rent a little cottage for a month in the summer. That, to me, coming from the desert, was like a pilgrimage. I just loved everything about the ocean. Flash-forward to 1987, maybe the fifth or sixth year of Cheers: I moved into a neighborhood in Santa Monica and met an environmental lawyer named Robert Sulnick who was fighting Occidental Petroleum to try to keep them from drilling oil wells on Will Rogers State Beach, Santa Monica Bay. I joined, and we won, and we enjoyed each other’s company. And, really naively, we started an environmental group called the American Oceans Campaign that grew into a really well-respected organization. The more I hung around these brilliant scientists and lawyers, the more I learned, and it became this conversation that I love to this day. It’s this huge potential environmental disaster that we can actually turn around. And we are. It’s become this kind of hopeful story: If we save our oceans and restore our fisheries to a healthy place, we could literally feed one billion people a day, sustainably, forever.

People like to talk about the Green Revolution, arable land, and improvements in farming, but I’ve never thought about applying those same principles to the oceans—which obviously make up a vastly higher percentage of the planet.

Absolutely. Matter of fact, part of the argument is that if you care about land, animals, and forests, then you must take care of the oceans. Because if you get your fisheries to be sustainably harvested, which is doable, then it really is the perfect protein. It takes such a huge amount of stress off of the land if we manage our oceans correctly.

I know we don’t have much time left, but I just wanted to mention that I’m from Arkansas. I grew up in Little Rock, not far from your wife’s hometown of Newport.

Oh, that’s fantastic! Really? Are you kidding me? Been there recently?

My parents live there, and my brother and his kids, so I go back fairly regularly.

Well, tell them please go to the restaurant South on Main, in Little Rock.

I’ve been there. It’s excellent.

Oh, that’s fantastic. Mary’s niece and her husband run it—he’s a chef, Matt Bell. She runs it and keeps it afloat, and we are partners with them in that. It’s a great music venue, too. A bunch of musicians come through. I’m so glad you’ve been there.

How do you feel about being an honorary Arkansan?

I feel so welcomed by that state. Seriously, if I’m walking through an airport and anyone says “Little Rock,” “North Little Rock,” or “Mary Nell”—which is what people who knew my wife in Little Rock call her—if I hear any combination of that, we’ve been known to miss airplanes talking to people.

Speaking of your wife, one of the jokes on Curb Your Enthusiasm is that Mary gets along really well with Larry David, who doesn’t get along with anybody. Is she as easy to get along with in real life?

She is very approachable, yes indeed. Most people will take a second look at me and go, “Well, I guess he’s not that big of an idiot, if she’s with him.”

Brooklyn-based writer and editor Hunter R. Slaton aspires to play a loosely fictionalized version of himself on Curb Your Enthusiasm someday.