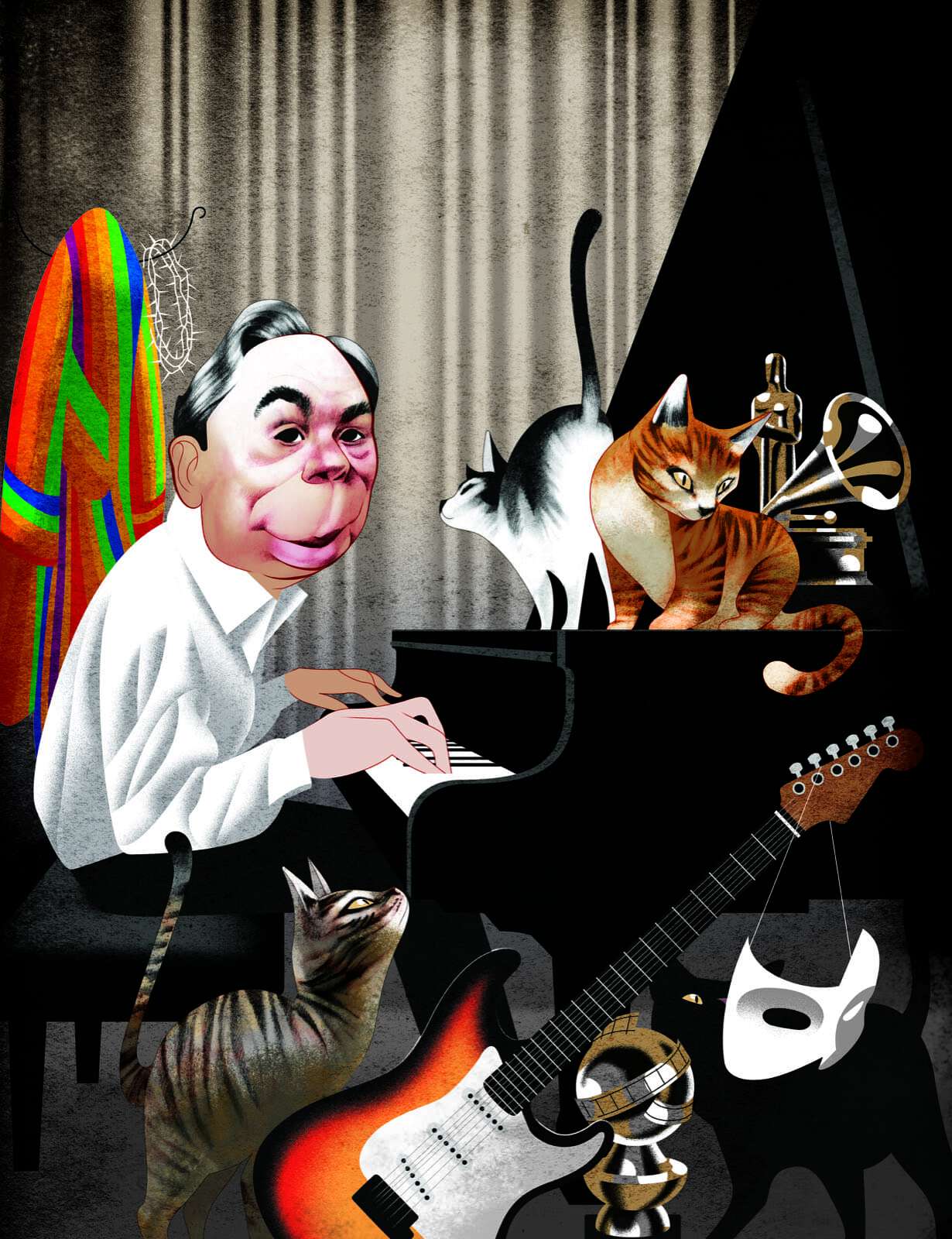

The remarkable thing about Andrew Lloyd Webber isn’t the awards he’s amassed (an Oscar, a Golden Globe, seven Tonys, three Grammys, a knighthood…) or the megahits he’s composed (The Phantom of the Opera, Jesus Christ Superstar, Cats, Evita…) or the more than $6 billion that Phantom alone has grossed during its 30-year run. It isn’t even the fact that Lloyd Webber ushered in the kind of lavish, spectacle-driven, cultish musicals we take for granted today—without him there would be no Lion King, no Wicked.

What’s most striking about Lloyd Webber is that, with a half-century of musical theater behind him, he exhibits the kind of earnest enthusiasm you’d expect of someone who just got his first favorable review. Of course, there is plenty of the hardened veteran in the 68-year-old, too. This is, after all, a man who described a bout with prostate cancer as “annoying” because it distracted him from his work.

Right now, he has no such issues. This month sees an open-air production of Superstar opening in London (timed to honor the show’s 45th anniversary), a revival of Cats hitting Broadway (with a movie in the works), and preparations underway for the London debut of his latest Broadway show, School of Rock.

Hemispheres spoke with Lloyd Webber in London, on the day he learned School of Rock had been nominated for four Tony Awards, including Best Musical.

Hemispheres: Hello.

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Oh, hello. Hi. Good afternoon. Sorry I’ve been a little bit evasive this afternoon.

H: Well, if you’re going to be late, a bunch of Tony nominations is as good an excuse as any. Not that you’re resting on your laurels. This month, among other things, you’ll have three shows running on Broadway at the same time.

ALW: I had three missing years due to illness and things. I turned the corner 18 months ago, and I’m not only trying to make up for those missing years, I’m just enjoying it.

H: School of Rock has apparently been a joy. I’m sure you’re aware of the old dictum: Never work with animals, children, or Lindsay Lohan. The show has disproved at least one of those.

ALW: Yes, the kids have been fantastic. But then, if you look at Cats, I haven’t done too badly with animals, either.

H: Only Lindsay Lohan to go.

ALW: There’s time. But the joy of this show: It’s almost 50 years since I did Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, which started its life in a school, and School of Rock is sort of bringing me full circle. I love working with young people, and I passionately believe in the importance of music in education.

H: For you, it’s more than simply, Oh, give them a violin and they’ll play it after math class. You believe music plays an important role in a child’s development.

ALW: Yes, absolutely. My foundation has led to 3,000 children being given violins. The idea isn’t to turn them into great classical musicians. Music liberates children; it helps in so many disciplines, including math.

H: You were an accomplished musician as a child, playing the violin at age three, writing your own music at six. Any plans to revive that material?

ALW: Oh dear. Well, some of my music was published when I was about nine. I’d forgotten about it, and I got very excited when someone said they’d found a copy. I was thinking that, as I enter old age, there might be a hit in there I could plunder. Sadly, there wasn’t.

H: How has the business changed since those early days?

ALW: I think the big difference now is that the costs of putting on a musical are so high. On Broadway, unless you’re grossing $1 million a week, you’re not even in the game; you haven’t even started to repay your debts. School of Rock is a smaller production, but it cost $14.5 million. It’s becoming very hard to put on a musical.

H: That’s because every show has to be a spectacle, a blockbuster. Do you take any blame for that?

ALW: Absolutely not—I so refute that. Every show of mine, every single one, without any exception whatsoever, has started in a simple way, with very little scenery, very little staging, including Phantom of the Opera and Cats. Even though they look elaborate, they’re both very simple shows. I don’t understand where that idea comes from, because it isn’t the case.

H: OK. This is a weird question, but do you have any favorites among your own work, something you hum while doing the dishes?

ALW: Not really. It’s fair to say, like children, I have reasons for liking all of them. They are also written for a particular reason at a particular time. As a musical dramatist, I try to imagine: If I were this character, how would I put that into music? So it’s funny for me to have Norma Desmond [Sunset Boulevard, which was revived with Glenn Close in London this spring], who’s a psychological study in madness, back to back with the Jack Black character [in School of Rock]. People might say, “My gosh, it’s the same composer!” You can have many sides to yourself.

Every show of mine, every single one, without any exception whatsoever, has started in a simple way.

H: How do tunes come to you? In the shower?

ALW: Sometimes a melody comes to you out of the blue; sometimes it takes a while. There isn’t a rule. You know the song “No Matter What”? I wrote that very, very fast. It just came to me.

H: How do you know that you’ve created a melody and not just remembered it from something else?

ALW: As you get older, you worry and worry and worry about that. I remember when I wrote “No Matter What,” I thought, “I must get that one double-double-double-checked.” And it hadn’t been done before. You can’t be absolutely sure of anything when it comes to creation, but I get a pretty good idea. And, you know, I certainly haven’t been caught out lately. [Laughs.]

H: One thing that’s defined your career, starting with your first musical, about an orphanage, is a willingness to take risks. Cats, Jesus, fascist dictators—these aren’t obvious subjects for musical theater.

ALW: Actually, the orphanage thing is an example of why you should take risks. That was written at a time when everyone was trying to do Johnny Cockney after Oliver! Luckily, that one didn’t get made. We lost the script, thank goodness. But Evita isn’t quite what you said it is; it’s very much a product of the 1970s, with miners’ strikes and private armies on the street. It’s an allegory, if you like, using an extremist in Argentina to say that this could happen anywhere.

H: Fair enough, but miners’ strikes and street brawls aren’t really the stuff of musical theatre.

ALW: You’ve got to take a bit of risk—of course you do. You have to tackle interesting subjects or, in the end, you’ll be doing fairy stories.

H: An inevitable result of taking these sorts of chances is that sometimes they’re not going to work. A few years ago, you did Stephen Ward, about a socialite who committed suicide in the aftermath of a political scandal. That didn’t seem the most suitable subject for a musical, and, in hindsight, maybe it wasn’t. [The show closed after four months.]

ALW: I think it was a great subject for a musical. One problem is that I was very, very ill during that, and didn’t get the chance to work on it properly. But Stephen Ward is a fantastic subject. We’re going back over it, to put right some of the things that went wrong.

H: You’ve been described as “a perfectionist” and “volatile,” which sound like code words. Are you difficult to work with?

ALW: I don’t know. I mean, we have a very happy time on School; we’ve had a fantastic time with that. But I do care passionately about the quality of the work. I feel annoyed that I had those three years where I wasn’t able to give my best, but I was still trying. I think I really should have said, “I can’t do this.” Obviously, when you care, and other people are not performing or aren’t up to scratch, then you have to say so. I’m not one to mince my words.

H: You’re also known for being very focused on the visual side of things.

ALW: Oh, yes, it’s absolutely critical for a musical that the design is right. The look of a musical is absolutely vital to its success. As someone said to me a long time ago, you can’t listen to music if you can’t look at it.

Ink Global U.S. editor Chris Wright is proud to announce that he can sing every single word in Jesus Christ Superstar, from the first song to the last, badly.