While Traverse City may be known as the Cherry Capital of the World, what really defines it is water. Originally a trade route stop for the Anishinabe people, the city is perched at the southern end of Lake Michigan’s Grand Traverse Bay, which is bisected by the Old Mission Peninsula, with the Leelanau Peninsula just to the west. Its present-day name came from French-Canadian fur traders, who called crossing the mouth of the bay “la grand traverse” (“the long crossing”). In the late 19th century, the lake was a critical conduit for the region’s booming lumber industry, and in the 20th century it served as the main attraction for vacationers escaping industrial Detroit. Today, the “inland sea” helps create an ideal climate for the region’s booming wine industry and locavore food scene, and it draws outdoorsy types to surf its waves and climb the magnificent sand dunes on its shores. Welcome to the third coast.

Day 1

A former asylum, an e-bike ride, and a sail on the lake

Focaccia bread pudding topped with kale and pork ragu, slow-roasted brisket on a vegetable waffle blanketed with crispy leeks— it’s not even 10 a.m. and my first morning in Michigan is off to an incredible start, thanks to the breakfast-only restaurant Sugar2Salt. I’m grateful I brought my friend Tova along, because that means we can try more of the menu—including a piece of dirty chai coffee cake.

Did I mention we’re sitting in a rehabbed building that’s part of the former Northern Michigan Asylum complex?

The campus housed patients from 1885 until 1989, and after closing it was nearly demolished. A local development group intervened in the early 2000s, keeping much of the Victorian-Italianate architecture intact and creating The Village at Grand Traverse Commons, which boasts apartments, boutiques, restaurants, a winery, and even a Saturday farmer’s market. After breakfast, Tova and I head to the cellar of Building 50, the former main building (now home to several shops), where we meet Vanessa Vance, the guide for our historic walking tour. Vance spent her adolescence on the grounds of the operating asylum back in the 1970s, after her father took over as superintendent, and she sums up the Village’s contemporary success with a question: “Who would want to live and recreate at the site of a former asylum? Everybody—that’s who.”

As she leads our group from a restored chapel to a still-intact 1883 brick steam tunnel, she gives a rapid-fire rundown of the complex’s architectural history: It was designed according to a Quaker philosophy stressing the healing powers of light, fresh air, and a beautiful environment. She also offers personal details, recalling a patient who earned the nickname “Houdini” because he escaped so many times, getting hamburgers with her dad at the asylum canteen, and playing with her BB guns on the grounds. By the end of the tour, Tova and I are convinced Vance needs her own TV show.

From here, we drive 10 minutes east to our hotel, the Delamar Traverse City, set at the southern end of West Grand Traverse Bay. Seeking to take in a little more of the scenery and sunshine, we walk a few blocks to Brick Wheels, an adventure gear shop that offers e-bike rentals. Within minutes, we’re marveling at the power of pedal-assist and zooming toward the Boardman Lake Loop. Completed last year, this four-mile route is the latest addition to the Traverse Area Recreation Trail system, which encompasses roughly 100 miles of trails in and around Traverse City. We ride over a winding wooden boardwalk and around the glassy lake, past geese bobbing in the water and plenty of walkers, cyclists, and kayakers. It’s clear that this is not the kind of city where people let a beautiful day pass without taking advantage.

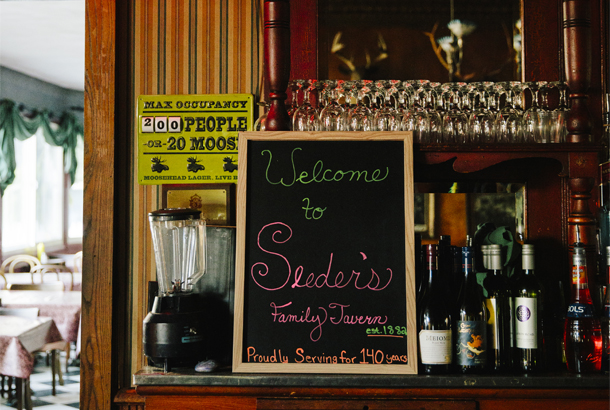

By the time we drop off the bikes, we’re ready for lunch at Michigan’s longest continuously running restaurant, Sleder’s Family Tavern, which opened its doors in 1882. Back then, west Traverse City was known as “Slabtown,” because the area’s many Czech immigrant millworkers built their homes with slabs of lumber mill scrap. The menu offers an array of classic pub grub, and we refuel with Diet Cokes, a club sandwich, and a cheeseburger. When I ask our server about the small stepladder beneath the moose’s head that hangs over the entrance to the back room, he tells us it’s so we can “smooch the moose,” who is apparently named Randolph, for good luck. We decide to pass on kissing Randolph—perhaps tempting fate, since we’re about to set sail on Grand Traverse Bay, which has seen its fair share of shipwrecks over the years.

It’s just a 20-minute drive up the Leelanau Peninsula to Suttons Bay, where we meet Juliana Lisuk, the associate director of Inland Seas Education Association. The organization runs programs aboard replicas of the 18th-century tall ships that hauled timber around the Great Lakes. After we learn how to raise the sails and begin cruising up Suttons Bay, the ship’s captain, Lily Heyns, calls for a moment of silence. “Breathe in, breathe out,” she says, then adds, “That breath is brought to you by phytoplankton.” As Lisuk explains, phytoplankton and zooplankton are the basis of the Great Lakes’ food web, and they’re under existential threat. Quagga mussels, an invasive species introduced by ocean-going cargo ships, are filtering phytoplankton out of the water. “This makes the water really clear but also removes a fundamental food source for the lake’s fish populations,” including salmon and whitefish, “and that has a ripple effect on the ecosystem.” As the breeze propels us toward the mouth of Suttons Bay, past paddleboards and pontoon boats, Lisuk paints a picture of what the lake would’ve felt like in centuries past: “I love to imagine hundreds of schooners out here, like in the late 1800s.” She also points out that the Great Lakes hold 20 percent of the entire world’s surface freshwater, and in recent years climate change has caused higher lake temperatures that can trigger toxic algal blooms. “If we’re not protecting the lakes,” she says, “it’s not like they’re going to be refilled.”

Back on land, we return to downtown Traverse, where we’re having dinner at a place that honors the local ecosystem in a different way. The Cooks’ House has been a leader in locavore cuisine since 2008, and 15 years later it’s as hard as ever to snag one of its 26 seats. Business partners Eric Patterson and Jennifer Blakeslee came to Traverse City, Blakeslee’s hometown, after earning a Michelin star cooking for celebrity chef Andre Rochat in Las Vegas. “When we came here, we weren’t sure if people were ready for what we wanted to do,” Patterson says, adding that it didn’t take long before they realized “people would eat anything.” As soon as I sample the first dish from our five-course tasting menu—a “tomato tea” so rich I swear bones have to be involved—I also decide I’m willing to eat anything they serve.

The cozy environment leads to chats with neighboring tables, and by the time we’re moving from Americanos to wine and diving into our crispy-skinned black cod with parsnip purée, we’ve gotten a list of local recommendations and the email address of a couple celebrating their 12th anniversary. After dessert—blueberries, cream, and homemade shortbread—we trundle back to the hotel, on a path so close to Lake Michigan we can hear its dark waves lapping the shore.

Day 2

Inuit art, a historic lighthouse, and lots of local wine

We greet the day at Hexenbelle, a plant-filled café with Palestinian-inspired fare in Traverse City’s Warehouse District, which in the 19th century was home to canning, candy, and wood dish companies. We enjoy cups of Damascus Gate coffee spiced with cardamom, clove, rose, and saffron, as well as ful mudammas (a fava bean stew topped with a fried egg) and a fatayer pastry stuffed with feta and spinach.

Fueled up for the day, we drive five minutes along the bay to The Dennos Museum Center at Northwestern Michigan College, which has one of the largest collections of Inuit art in the U.S. When we meet museum engagement manager Chelsie Niemi, Tova and I have one immediate question: How did so much art from the Arctic Circle land in Northern Michigan? As she explains, it all began in the 1960s, when a Chicago publishing executive who summered in nearby Leland donated his collection of rare Inuit carvings to the college. Today, the museum has more than 2,000 Inuit prints and sculptures in its permanent collection, many of them portraying modern Inuit life. As we walk among pieces depicting traditional Inuit games, fishing, and the spirit world, Tova and I are most taken with images of Sedna, the mermaid-like Mother of the Sea in Inuit mythology. Who, or what, we wonder, would be the mother of the Great Lakes?

It’s a beautiful drive over rolling hills and past fruit stands, a lavender farm, and vineyards to the Mission Point Lighthouse on Old Mission Peninsula. Michigan has the most lighthouses of any state in the country (129); this one was built in 1870, after a nearby shipwreck, and stayed illuminated until 1933. In addition to its historical value, the lighthouse is geographically significant: It sits on the 45th parallel, halfway between the North Pole and the equator. This is roughly the same latitude as some of Europe’s best-known wine regions, including Bordeaux and Piedmont, which explains in part how the Old Mission Peninsula and the Leelanau Peninsula have become known as the Napa of the Midwest. Lake Michigan helps create a cooling effect in the summer and a warming effect in the fall, extending the growing season, and glacial soils make the peninsulas—both of which are designated as American Viticultural Areas—ideal for growing all kinds of fruit (including, of course, cherries).

On our way back down the peninsula, we decide to make a quick stop to sample some of the local juice at 2 Lads Winery, which is known for its cool-climate reds. Inside the hilltop tasting room, we take in views of East Grand Traverse Bay through floor-to-ceiling windows while sampling a flight of staff favorites, including a 2020 cabernet franc and a 2021 rosé of pinot gris. The cab franc is full-bodied and berry-forward, and the rosé dry and almost citrusy— perfect sips to whet our appetites for a late lunch.

Back in Traverse City, we swing by The Little Fleet, a bar that hosts food trucks from April to October. We order pork belly bao buns, fried brussels sprouts with nu,ó,c châm, and a soy ginger tofu rice bowl from the Vietnamese truck Good on Wheels. We don’t really need dessert, but just a couple of blocks away is Grand Traverse Pie Company, and who could say no to tart cherry crumb pie?

Now that we’ve lined our stomachs, it’s time to get back to wine. Our next stop is the Leelanau Peninsula’s venerable Black Star Farms, which has been welcoming guests since 1998. Black Star managing owner Sherri Campbell Fenton took over the operation from her parents in 2016, and as she walks us through the verdant 160-acre estate, past grazing horses and red barns, she recounts how its 2017 dry riesling won Best in Show at an international riesling competition. “The judge pulled back the label,” Fenton says, “and went, ‘Where’s Michigan?’” Northern Michigan, she explains, is still a young wine region: “The oldest vines here are about 50 years old, and most of them have been put in the ground in the last 20, which still isn’t a lot of time. The wines get better as your roots get deeper.”

Our tour ends at Black Star’s tasting room, where we try a dry riesling, a pinot noir, a gamay noir, and a sur lie chardonnay that’s grassy and citrusy—perfect for summer afternoon drinking. Maybe a little too perfect; it’s probably time to get some more food.

After a quick stop to pick up a cave-aged raclette at Leelanau Cheese, we head south, toward the base of the peninsula, for dinner at Farm Club, a restaurant, brewery, bakery, and, yes, farm. We sit at a picnic table, and, as the sun sets and the twinkle lights come on, we feast on crispy fried onion rings made with bulbs harvested that day (“You can actually taste the onion!” Tova marvels); an heirloom tomato salad topped with candied pepitas and a ginger dressing; polenta with sausage, rapini, and sweet peppers; and a peach clafouti. We wash it all down with house-brewed beers—a lemongrass farmhouse ale for me and a fresh hop pale ale for Tova. Once again, Michigan’s agricultural bounty provides. We stay until the stars begin to appear in the sky, but no later. We’ve got an early wakeup call tomorrow.

Day 3

Surfing on the lake, climbing sand dunes, and visiting fishing shanties

“This is the perfect day to learn how to surf,” Ella Skrocki chirps as I contort my body into a wet suit at Empire Beach, a half-hour’s drive west of Traverse City, on the Leelanau Peninsula. “Last night’s storm brought us some big wind and waves, and we’re seeing the residual ground swell today.” Skrocki and her sister, Annabel—the second generation, along with their brother, Reiss, behind Sleeping Bear Surf, which became the first full-service surf shop in Michigan when their parents, Beryl and Frank, opened it in 2004—are set to teach me and a few other beginners how to surf on Lake Michigan.

While the lake might not have the massive swells of Oahu, surfing here is its own art. First, you need wind to blow across the water and create waves. This means that Great Lakes surfers have to pay close attention to forecasts. Peak season runs from August through winter, when storms moving across the country react with the warm water to create the biggest waves. (Surfing in the snow is a thing.) “You have to be really spontaneous and flexible and brave,” Ella says. “Scouting spots and getting skunked for three hours, it’s all part of the experience, and it makes surfing the Great Lakes really rewarding.” Annabel chimes in: “It’s not for the faint of heart.” Tova, who’s fending off a cold, watches and laughs as my classmates and I practice popping up on foam boards on the beach. I’ll be the first to admit, I’m more boogie boarder than surfer.

As the waves start rolling in, we swim out to Ella and Annabel, who tell us when to start paddling and push us into the waves. After several attempts that end with a mouthful of lake water—“It’s like that scene in Forgetting Sarah Marshall,” Annabel advises, “Do less!”—I finally catch a wave and cruise to the beach, triumphant. If it feels this good when the waves are handed to me on a silver platter, I can only imagine the high after you’ve spent hours seeking them out. Back at the shop after the lesson, Ella reflects on what the growing popularity of the region might mean for its tight-knit surf scene. “When we were growing up, every surfer from Chicago to Duluth knew, or knew of, one another,” she says. “Now we’re in a transition phase, faced with the question, Can we hold onto that awesome community energy?”

The sisters recommend picking up post-surfing hot chocolates at Grocer’s Daughter Chocolate and sandwiches at Shipwreck Café in the village of Empire. Snacks in hand, we hike the three-quarter-mile trail through sugar maple, beech, and hemlock trees to Empire Bluff. The trail is part of the 35-mile-long Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, which is famous for its massive rolling dunes, wonders that were formed when melting Ice Age glaciers deposited glacial sand here. We find a bench at the top of Empire Bluff, more than 400 feet above the lake, and marvel at how turquoise the water is; it feels almost as if we actually are on Oahu.

Sandwiches consumed, we head back to the car and get on the Pierce Stocking Scenic Drive, a 7.4-mile loop through the park that offers one majestic dune-top vista after another. At the Lake Michigan Overlook, we get our best view of the park’s namesake Sleeping Bear Dune. Its name comes from an Anishinabe story about a mother bear who is sleeping as she waits for her lost cubs. At one point, the humps of the Sleeping Bear Dune did look ursine, but decades of erosion have ruined the resemblance. The dunes are stomach-churningly steep, and at several scenic overlooks we’re surprised to see people climbing up them. We also notice a few warning signs: “Avoid getting stuck at the bottom! The only way out is up. Rescues cost $3,000.”

We decide to do The Dune Climb, a park-sanctioned option about five miles north of Empire. Scaling the wall of sand makes for a surreal experience; only 10 minutes into the climb, we’ve lost sight of the parking lot below, leaving only sand in our view. When we reach the top, we catch sight of Glen Lake, which used to be part of Lake Michigan but is now cut off by a sandbar. As we slosh our way back down through the sand, we watch other people kick off their shoes, while kids hurtle fearlessly down the slope. “I wish we had a sled, or at least a baking sheet,” Tova says. I wholeheartedly agree.

Shoes full of sand, we get back in the car and head north toward Leland, the quaint town that occupies the narrow isthmus separating Lake Michigan from Lake Leelanau. Our first stop is the collection of 14 weathered wood shanties along the Leland River known as Fishtown, a bustling commercial fishing hub during the first half of the 20th century that last year made it onto the National Register of Historic Places. While much of the local lake trout and whitefish populations have been wiped out by overfishing and invasive species, the Fishtown Preservation Society still maintains two active commercial fishing boats, the Joy and the Janice Sue. We wander through the array of shops that now occupy the buildings, including the Village Cheese Shanty; the Art Shanty, a gallery space in a former ice house; and Carlson’s Fishery, which has been famous for its smoked whitefish for more than a century.

We drop our bags at Falling Waters Lodge, an updated 1960s hotel that overlooks the Leland River Dam. From here, it’s a five-minute walk back across the river to dinner at The Riverside Inn, a local staple since 1902. We sip Lake Life cocktails (gin, raspberry, simple syrup, lime juice, and ginger beer) and dig into smoked whitefish pâté from Carlson’s; a bowl of sweet corn radiatore with bacon, spinach, and basil; and a lamb chop topped with chimichurri.

After dinner, we walk down the road to Van’s Beach for the sunset. We plop down in the sand and watch the horizon glow gold, then pink. Even though I know, rationally, that we’re on the pinky of the Michigan mitten, overlooking a lake in the middle of the country, it still feels like the edge of the world.

Traversing Michigan: United flies to Traverse City year-round via Chicago O’Hare, and also through Denver, New York, and Washington, D.C., during the peak summer season—the best time to enjoy Michigan’s famous fresh cherries.