Signs and murals around Denver declare that “No Coast is the Best Coast,” a proclamation that’s rooted in the Mile High City’s refusal to play the game by any rules other than its own. Here, flannel can be formal; greeting strangers doesn’t make you weird; and when people ask what you do, they mean, How do you spend your time outside? The city is doing much to embrace its rich, diverse history, and yet it’s also moving into the future with innovative restaurants, imagination-defying art, and, yes, killer craft beer. Yet, no matter how high Denver’s profile rises, all it takes is a look west, toward the rugged Rocky Mountains—the original skyscrapers—to remember that this is still Colorado, and nature is never far away.

Day 1

Breakfast burritos, secret stories in street art, and breweries like no other

I wake up to sunlight streaming through the windows of my room at Catbird hotel, in Denver’s hip RiNo Art District. Despite Colorado’s reputation as a winter wonderland, its capital city is said to see sunshine nearly 300 days a year, making the sunscreen and shades I packed as essential as the sturdy boots and beanie I’m donning against the cold.

Although my extended stay–style room is outfitted with a full kitchen, I’m craving a quintessentially Denver meal, so I catch a rideshare to Onefold, near Union Station, for a breakfast burrito smothered in green chile. Rapidly growing Denver is still figuring out what defines it as a city, including its food. “What’s getting me excited is seeing all the diversity that’s coming out,” says Yesenia Chinchilla, the creator behind the popular @DenverFoodScene social media account, who joins me for breakfast. This used to be strictly a steak and burger town, but no more. “Denver’s really accepting,” Chinchilla notes. “If there’s a new restaurant, [people are] willing to try it.” As I bite into the impossibly soft tortilla of my burrito, I can’t wait to sample more of what the city has to offer.

Full and energized, I walk 20 minutes back to the southern edge of RiNo (short for River North), watching the vibe shift from upscale-downtown to revitalizing-industrial. I’m meeting Jana Novak, guide and co-owner of Denver Graffiti Tour, for an exploration of the district’s famed street art—and the social, political, and historical context that created it.

“Denver was one of the first cities to embrace graffiti as art,” Novak tells me as I admire a geometric mural, Pat Milbery’s Love This City, at the intersection of North Broadway and Arapahoe. An annual street art festival that started in 2010 was part of a rebranding of much of the historically Black Five Points neighborhood into RiNo—which furthered gentrification issues but also provided space for work by Black and Latinx artists who were shunned by fine art houses.

Over the next two hours, Novak shows me how this conflict—along with themes of racial identity, disability, and food and housing insecurity—is reflected in RiNo’s street art. Much of it is playful and experimental, including an alleyway mural, i am her by A.L. Grime, that requires AR glasses to be seen properly, and Larimer Boy/Girl, which Jeremy Burns painted onto a building’s side fins so viewers see something different from every angle. “You will see rhinos everywhere here,” Novak adds, referring to the district’s unofficial mascot. (Even the bike lane features an icon of a cycling rhino.)

I keep things quick and local for lunch—grabbing a diavola pizza at Denver Central Market, one of several curated food halls springing up around the city—because I have a big undertaking for this afternoon. Denver is famous for its beer scene, with more than 150 breweries to choose from, so I’m letting Blake Knoll, the guide of eTuk Ride’s Drink Denver Craft Brewery Crawl, pick three for me.

“Denver is like an amusement park for beer drinkers,” Knoll says as we settle beneath blankets to protect against the cold air in the open tuk tuk. The stiff competition means brewers have to get creative to stand out—and drinkers reap the rewards. I get my first taste of this phenomenon, a pint of Astro Blaster Pilsner, at Spangalang Brewery, located in a former DMV building at the center of Five Points. The neighborhood, once known as the Harlem of the West, was a product of segregation but became celebrated as a crucible for Black excellence, and Spangalang’s name—a reference to a classic jazz cymbal rhythm—is an homage to the area’s history.

Next, we zip over to Tivoli Brewing, Denver’s first, founded in 1859. Tivoli closed in 1969 but was brought back to life in 2012—albeit after a student union for three local universities had already moved in. Now, study groups and lager lovers mingle in the historic space. While enjoying my second pilsner of the day, I learn how beer and the outdoors go hand in hand here. “When you think of Colorado, you think of hiking and IPAs,” says Gage, a medical student and Centennial State native who’s also on the tour. He tells me there’s nothing like summiting a fourteener—a mountain that exceeds 14,000 feet in elevation—and then drinking the tall boy you hauled up there. I promise him I’ll try it one day (but not in winter).

Finally, we visit TRVE Brewing, where I’m greeted by a blast of heavy metal as I open the door. The interior is lit by electric candles, and the long-haired, tattooed staff is no gimmick: “They don’t hire off-brand,” Gage says, toasting the place’s commitment to the bit with a Strange Gateways black lager.

The tour’s over, but there’s one more brewery I want to check out: Ratio Beerworks, a mural-swathed spot started by two guys from the punk rock scene. I’ve never really been a beer person, but as I sip a Cityscapes lager, I think Denver might be turning me into one.

My dinner reservations are inside the market hall at The Source Hotel, a former iron factory turned chic hotel, restaurant, and shopping complex, so as an appetizer I peek my head into a few stores. I ogle vintage band tees and Levi’s jean jackets at Darklands, and at the florist shop Beet & Yarrow I find a modern candleholder to take home.

Souvenir in hand, I take my table at Bellota, where Monterrey, Mexico–born Manny Barella earned a 2022 James Beard Award nomination for Emerging Chef. One bite of the esquites appetizer— basically a salad version of Mexican street corn, punched up here with the aromatic herb epazote—and I can see why. The rib eye, pibil, and shrimp tacos are the best I’ve had since I was last in Mexico, and as full as I am, the churros convince me that a separate dessert stomach really does exist.

I head out into the cold and make my way back to one of the murals I saw this morning: a vivid portrait of Billie Holiday on the exterior of the jazz club Nocturne. I slip into the dimly lit venue, order a dirty martini, and melt into the sultry tones of a night out in Denver.

Day 2

Indigenous art and food, farm-to-table whiskey, and psychedelic art

It’s snowing as I walk past Union Station, the Beaux-Arts centerpiece of Denver’s oldest neighborhood. LoDo, short for Lower Downtown, dates to 1858, when gold miners set up shop here. Like much of the city, it has been revitalized within the last decade, going from a ramshackle area with boarded-up storefronts to the bustling home of high-end restaurants, boutique shops, and swanky bars.

I pop into one of these new spots, Little Owl Coffee, for a vanilla latte and churro croissant. Sufficiently caffeinated, I head back to Union Station and duck into the famed indie bookstore Tattered Cover, picking up Pam Houston’s Deep Creek, a memoir about homesteading the Colorado Rockies.

Three blocks east, I find the new Dairy Block, a former dairy that was recently redeveloped into a vibrant micro-district. It has restaurants, shopping, galleries, and The Maven hotel, where I’m staying tonight. At check-in, front desk clerk Dawn points out the 1955 Airstream trailer in the lobby, advising me to stop by for the guest happy hour tonight. “Getting a drink from a camper is such a Colorado thing to do,” she says with a smile.

Right now, I’m ready to drink in some culture, so I take a rideshare over to the Denver Art Museum. The docents direct me past the Monet paintings and across the Skybridge to the recently updated Martin Building, where I find the Indigenous Arts of North America galleries, a permanent exhibit showcasing works by contemporary Native American artists. The dichotomies are striking: There’s celebration and critique, darkness and color, historical and modern perspectives. It’s a collection that defies stereotype. Upon leaving the museum, I notice the lampposts and poles outside are covered in admission stickers from past guests, so I add mine to the community-generated mosaic.

My eyes are full, but my stomach is not, so I head for lunch with local legend and culinary historian Adrian Miller, who won a 2022 James Beard Award for his third book, Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue. Over medicine wheel nachos and fry bread tacos with shredded bison meat at fast-casual Tocabe, Denver’s only brick-and-mortar restaurant serving Native American food, we talk about the city’s rising reputation as a diverse dining destination. “It used to be, ‘Does it play in Peoria?’” he says. “Now it’s, ‘Does it dine in Denver?’”

Miller also delights in telling me about the overlooked history—and present-day renaissance—of Colorado barbecue. In 1890, African American chef Columbus B. Hill grilled for 25,000 Denver denizens to celebrate the Colorado Capitol’s cornerstone being laid. “This goes way back,” he says. “We just got away from it.” The city’s modern pitmasters are even defining their regional flavor with meats such as lamb and bison, the same as Hill cooked.

I could happily talk about food with Miller all day, but I have an appointment I can’t miss: a custom cowboy-hat fitting with third-generation hat shaper Parker Thomas in the nearby neighborhood of Highland. Sporting snakeskin boots with a matching belt, Thomas looks as if he stepped straight out of the Old West, but he clearly means to extend his grandfather’s legacy beyond the realm of cowboys and into the world of fashion. “I can go to Paris and do Fashion Week, and then a week later be at the National Finals Rodeo in Las Vegas,” he says—because he has.

The “blank” hat I pick out is a grayish color called silver belly, and for the quality we land on 7x, which refers to the amount of beaver fur blended into the wool (the more beaver the better, apparently). Thomas brings the hat back and forth between my head and the steamer, sharing stories of his family and the rodeo without losing focus. He places the final product snugly on my head, removing a silver pin from his own hat and sticking it onto mine. “This shaping is called the Howdy Ma’am,” he says of the gently upturned brim, demonstrating the classic cowboy greeting with a smile. I do the same in the mirror, feeling as though I now officially belong on the Front Range.

Next, I head south for a tour and tasting at Laws Whiskey House. The industrial building is dark and moody inside, the air tinged with the telltale aroma of fermenting grain. These are locally sourced grains, I’m told; what makes Laws stand out is its focus on terroir. Of course, in Denver, you’d expect nothing less than a farm-to-table approach. “We want to be the Colorado thread in the fabric of American bourbon,” explains lead distiller Barb McDonald. The proof is in the glass I’m poured at the end—the whiskey is grain-forward, with a smooth, rich finish.

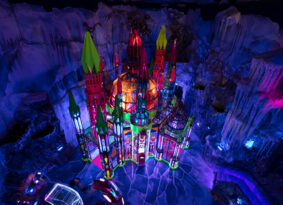

I stop by The Maven to stow my hat and grab my free beer from the lobby Airstream before making my way to Meow Wolf Denver: Convergence Station. This immersive, interactive installation, opened in 2021, is the collective work of hundreds of artists who filled four stories and 90,000 square feet with mind-bending rooms and mesmerizing encounters. It’s best experienced by surrendering to your psychedelic surroundings and letting your inner child run free. I allow myself to believe I’m in an alien transport hub connected to multiple worlds, investigating every new doorway and pressing whatever buttons appear before me. Somehow, I keep ending up back at the pipe organ in the Kaleidogothic Cathedral on the ice planet Eemia—and that’s fine by me.

My day ends back at Union Station, where I’m having dinner at the upscale northern Italian restaurant Tavernetta. The philosophy behind the decor is just enough—which is also how the kitchen cooks the pasta. I delight in how al dente my cacio e pepe rigatoni is, and the tiramisu is the perfect not-too-sweet end to one of my best meals in recent memory.

Across the alley, I slip into Sunday Vinyl, a wine bar known as much for its one-of-a-kind analog sound system as its bottles. I ask my server, Brendan, what I should pair with the expressive contralto of Amy Winehouse emitting from the speakers. “To me, this feels like Bordeaux,” he says, adding that music this sultry calls for a robust, decadent wine. I take my Château Prieuré-Lichine to the back of the bar, where I’m swept away by a perfectly triangulated, wine-infused sound bath.

Day 3

Hiking and biking the Rockies, watching alpenglow, and eating iconic burgers in Boulder

Soon into my 45-minute drive to Boulder, the skyscrapers of downtown Denver are overshadowed by the craggy peaks of the Rocky Mountains. Around here, there’s clearly no need to choose between urban living and outdoor activities.

I make way for professional athletes and carousing college students alike when I check into the historic (and supposedly haunted) Hotel Boulderado. I find myself gaping at the ornate stained-glass ceiling above the lobby and the 1906 Otis elevator that I could not begin to operate on my own, and I’m equal parts pleased and terrified that I’m staying in room 304, which paranormal investigators have reportedly identified as particularly rife with activity.

Boulder does not engender laziness, so I abandon my ghost(s?) and drive over to The Buff Restaurant for breakfast. The bustling diner has an extensive menu, and my server recommends a protein-packed meal to kick off an action-packed day: the Rustic Benedict with turkey and The White Buffalo mocha. I gobble it all down before heading out to learn why this city is such a magnet for cyclists.

“You have a town that’s surrounded by open space, and it’s all linked together by bike paths,” explains Joshua Baruch, the owner of Colorado Wilderness Rides and Guides, as he drives us to a trail on the south side of town. In 1967, Boulder residents became the first in the nation to vote to tax themselves for the purpose of buying land around the city, which today reaches nearly 45,000 acres. “It’s like the developers of Boulder knew that quality of life is enhanced with access to the outdoors.”

Although he trains Tour de France cyclists, Baruch gladly pedals along with me through several miles of relative flatland, pointing out bald eagle nests and chittering prairie dogs and greeting everyone we pass. With the fresh mountain air, access to the outdoors, and unabashedly friendly people, I’m starting to understand what quality of life looks like in practice.

I’ve worked up an appetite, so at the end of our ride I ask Baruch to drop me at The Sink, a burger joint that’s celebrating its 100th birthday this year. Entering the low-ceilinged restaurant is like stepping into a punk rocker’s fever dream. The walls burst with comical and political murals by the late artist Llloyd Kavich, and the ceiling is covered in signatures from graduating University of Colorado Boulder students. “All the history is in the tables,” adds co-owner Mark Heinritz, who points out a resin-trapped menu from 1947 and photos of visiting celebrities such as Guy Fieri, Anthony Bourdain, and former Sink janitor Robert Redford.

I order the house burger and end up chatting with a group who happen to be in town for their 50-year college reunion. I ask why they’ve chosen to celebrate at The Sink. “If you look up, half of those names are ours,” one of them jokes, causing the rest to laugh. “It’s ingrained in our DNA,” another replies, before they collectively thank Heinritz for keeping the tradition of Boulder’s most beloved restaurant intact.

Fueled up once more, I’m ready to take on the outdoors again. This time, I head to Chautauqua Park for a hike to see the famous Flatirons up close. There are plenty of hikers, runners, and dog guardians—the official, legal term in Boulder—ascending from the ranger station, and I’m glad to overhear that I’m not the only one struggling with the 5,800 feet of altitude.

“It burns the lungs different,” one hiker wheezes, while another breathlessly promises her friend that the view at the top is worth it. After many breaks, I make it as high as the ice will let me go without crampons, and find that the panorama of the Flatirons above and the city below is indeed worth the effort.

After a quick outfit change at the Boulderado, I walk a few blocks to the Boulder Dushanbe Teahouse for its afternoon tea service. The doors of the intricately carved and painted building—much of it made in Tajikistan—open with a whiff of jasmine, beckoning me forth into an even more ornate interior. I sit near a plant-filled fountain and order a rich black tea to accompany my three-tiered tray of goodies. As I nibble on a tiny blueberry cobbler, I overhear a woman at the table next door tell her date that this is her favorite place in Boulder. I can see why.

The sun is beginning to set, so I hurry over to Corrida to watch the Flatirons light up with alpenglow, a unique phenomenon in which the last rays of the sun make mountain peaks gleam red and orange. The Spanish restaurant’s rooftop offers an uninterrupted view, so I settle in next to an outdoor firepit and order a drink from the gin and tonic cart that’s rolling around as I take in Mother Nature’s show.

It’s just a few blocks to cozy Bramble & Hare, where I’m dining with the pleasantly sardonic owner, Eric Skokan. He tells me he sources nearly 90 percent of the restaurant’s ingredients from his own Black Cat Farm, and he doesn’t just mean the food: The banquette pillows are filled with wool from his sheep, and a handmade carousel in the bar is made from old farming equipment. Conversing like old friends, we discuss what makes Boulder such a special place as we enjoy butternut squash soup, Tunis lamb, and a bottle of tempranillo. “Everyone comes as they are,” he muses. “Pretension falls flat here.” It doesn’t seem like a bad place to live. Not at all.

I walk back to the Boulderado, but I’m not quite ready to join the ghosts in my room, so I head down to the basement, where a catacomb-like former speakeasy is now operating above board as License No. 1—so named because it was one of the first places in town to get a liquor license after the repeal of Prohibition. The bartender, John, recommends the Secret Handshake, which seems apt given the bar’s history. “I might be biased because I made it,” he admits, but he considers it a personal favorite. Much like my last three days, the smoky, citrusy scotch cocktail goes down easy.

Colorado’s Calling: Nonstop service to Denver is available from 155 U.S. cities and 17 international cities, and more than 100 additional cities have flights with just one stop.