The rock star is on a mission to make Arizona the next great American wine region

I’ve been told to watch out for rattlesnakes.

This is a new vineyard pest for me. Birds, bugs, disease—these are common across American wine regions. But rattlesnakes? As I tiptoe among grape-laden vines, the desert sun beating down on me, I stare at the rust-colored soil of the Agostina vineyard in Cornville, Arizona, and listen for the telltale rattle.

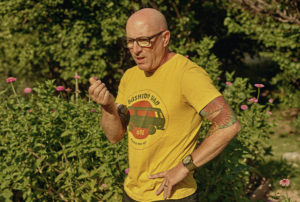

Rather than snakes, the creatures I encounter are a multicolored dragon and a giant black centipede, and they are tattooed on the arms of my guide for the afternoon, Maynard James Keenan. Around the world, he’s known as the front man of the rock bands Tool, A Perfect Circle, and Puscifer; he has sold millions of albums, topped the Billboard charts, and won four Grammys. In the Grand Canyon State, though, Keenan is recognized as a vintner and champion of local viticulture.

While plenty of musicians have “winemaker” on their résumé—Jay-Z, Mary J. Blige, Jon Bon Jovi, Snoop Dogg, Dave Matthews, to name a few—Keenan stands apart from the crowd. This isn’t merely an interest for Keenan, who grew up in the farming community of Mason County, Michigan, baling hay, harvesting peaches, and cultivating his family’s garden. Winemaking is a passion, something he felt called to pursue when he first visited Arizona’s Verde Valley back in 1995. “As we entered the Verde Valley, my heart started to race,” he wrote in a column for the Phoenix New Times in 2012. “By the time we got to Jerome, I was vibrating. We—my inner dialogue and myself—knew this was the place. This was like that moment when you realize you’ve just met your soulmate. You just know.”

Today, as he gazes over the rugged, hilly terrain, the 57-year-old can’t help but smile. “There’s nothing really holding you back,” he says when asked about the appeal of winemaking. “It’s all about just developing your senses and developing process, navigating chaos, rolling with the punches, and having a region that can present you with incredible fruit. If you have an area that can sustain that kind of fruit, you can become a winemaker.”

Keenan planted his first vines in 2000, and he now has four vineyard sites in the Verde Valley, which serve as the source of grapes for his Caduceus Cellars wines. He also owns the former Dos Cabezas vineyard in Willcox, which he renamed the Al Buhl Memorial Vineyard for the influential grape grower, and which supplies the grapes for his Merkin Vineyards wines. But Keenan is taking things a step further. He’s not only concerned with his wines (which, by the way, are delicious); he’s on a mission to make Arizona the next great American wine region. And if his music career is any indication, success is inevitable.

While it’s considered one of the U.S.’s younger wine regions, Arizona has a rich winemaking history. Missionaries are believed to have introduced viticulture to the area in the 1700s, and by the mid-1800s thirsty miners were raising glasses of red wine alongside beer and whiskey. The first commercial winery opened in Mesa in the 1880s, and around the same time a German immigrant, Henry Schuerman, started producing wines in the Verde Valley, not far from the present-day location of Keenan’s Caduceus Cellars. Prohibition, though, squashed all that. Vines were ripped out. Wine was poured down the drains. Schuerman was even jailed for trying to unload his supply.

The 21st Amendment ended Prohibition in 1933, but wine didn’t make a comeback here until the 1970s, when a University of Arizona soil scientist began growing grapes as an experiment. He and a team of researchers published a report in 1980 touting the region’s potential, and from their findings three major appellations have emerged: the Sonoita American Viticultural Area (AVA), about an hour southeast of Tucson; the Willcox AVA, a little over an hour east of Tucson; and the Verde Valley, which was granted AVA status in November.

The terroir differs wildly among these appellations. The Verde Valley contains more decomposed granite, volcanic, and limestone-layered soils, which means wines with more minerality. (“I’m not a big fan of that word,” Keenan says, “but it applies here.”) Willcox, meanwhile, is essentially an elevated desert playa, with alluvial soils that produce more obvious and approachable fruit. What the regions share, though, is a relatively high elevation, which Keenan credits for giving Arizona’s wines their distinctive character. “I’m farming anywhere between 3,200 and 5,000 feet, so we have big diurnal swings,” he says. “The heat is absolutely a factor, but the cooling off at night brings back that acid structure.”

In the late aughts, the Verde Valley Wine Consortium—an organization with more than 20 winery members and numerous local business affiliates that promotes and connects the wine community— sensed that the region could be on the cusp of something big. The consortium approached Yavapai College with a proposal to turn its Verde Valley satellite campus, which then focused on general studies such as math and English, into a viticulture and enology training center.

“I think the college understood that [there was potential], but there’s never extra money for that sort of thing,” says Michael Pierce, the co-owner of Bodega Pierce and Rolling View Vineyard. In 2009, to help goose the process, Keenan donated a one-acre vineyard of Negroamaro to the school. Other benefactors, inspired by Keenan’s gift, soon came on board, and in 2014 the Southwest Wine Center was born.

“It got the conversation going,” says Pierce, now the center’s viticulture and enology director. “If somebody is going to give a significant donation, then this could possibly work.”

Housed in a former racquetball gym, the center, which offers a two-year program in viticulture, comes complete with a teaching vineyard, an operating winery, and a tasting room. Think of it as UC Davis, but with a focus on growing grapes in a desert climate.

“I think the industry loves that this is here, because it helps establish a kind of legitimacy and also a neutral ground for conversations to happen,” Pierce says. “The program completely saved this campus.”

The Southwest Wine Center isn’t the only incubator of local talent that benefited from Keenan’s intervention. In 2011, Joe Bechard, a former winemaker at Page Springs Cellars, one of the biggest estates in the Verde Valley, and his wife, Kris Pothier, were trying to start their own label, Chateau Tumbleweed, but were short on funds. Lacking prospects for growth, they were considering leaving the state. “We had hit the glass ceiling in the Arizona wine industry,” Pothier says.

Then Keenan called, asking Bechard to work on his Merkin Vineyard wines, and to help him build out a new facility he had just bought. There was more, too: He wanted Chateau Tumbleweed to serve as a guinea pig for a new incubator space, Four Eight Wineworks.

Today, Four Eight is open to aspiring winemakers, following an application process that includes drawing up a five-year business plan. Those who are accepted can access a full suite of vinification equipment—normally a costly roadblock—while maintaining autonomy over their own brands. A number of associated labels, including Chateau Tumbleweed, Bodega Pierce, and Heart Wood Cellars, have flourished.

“He’s a good human,” Pothier, now the president of the Arizona Wine Growers Association, says of Keenan. “I don’t know that he ever had his heart in the idea that he was going to have a cooperative in perpetuity. It’s more like, ‘Here’s talent. I’m going to offer people opportunities that they otherwise couldn’t get on their own,’ which is an extremely generous thing. It takes an artistic brain to be able to see that way. I don’t think, otherwise, we’d be where we’re at.”

While the Four Eight facility is not open to the public, those who are curious can sample wines made there at a hybrid tasting room/retail shop in Jerome. On my visit, I chase a flight with a Twaffle (a tater tot–waffle mash-up) while pondering a Verde Valley Brazilian Jiu Jitsu–branded yoga mat (Keenan is an avid practitioner) and a rack of Puscifer T-shirts.

In yet another effort to push the local industry forward, Keenan and his wife, Jennifer (who is also the winery’s lab manager), teamed with a few other standout Arizona winemakers—among them Kelly and Todd Bostock of Dos Cabezas WineWorks, Kent and Lisa Callaghan of Callaghan Vineyards, and Rob and Sarah Fox Hammelman of Sand-Reckoner Vineyards—to cofound the Arizona Vignerons Alliance in 2015. Members submit wines biannually for evaluation by sommeliers outside the state.

Some controversy did ensue: The concept of being judged by industry peers—not to mention the possibility of being compared to wines from more venerable regions—made some local winemakers more prickly than desert cacti. Keenan, though, is quick to point out that the bar is set pretty low. “We weren’t looking for grand cru,” he says. “We weren’t saying that our wines are better than everybody else.”

Ultimately, the goal, aside from presenting Arizona wines to a broader audience, is an educational one. The evaluation process has resulted in the compilation of a database of winemaking knowledge specific to Arizona terroir—what Keenan sees as the true value of the Alliance’s work.

As the state’s industry has grown—Arizona now boasts more than 120 wineries, and production purportedly increased by 1,940 percent between 2003 and 2017—so have Keenan’s agricultural ambitions. Gardens thrive in the middle of the Agostina vineyard, thanks to Keenan’s father, Mike, who oversees the project; mushrooms flourish in an Airstream trailer on the Marzo vineyard property, and Keenan’s greenhouses provide produce for area restaurants, including his farm-to-table spot, Merkin Vineyards Osteria. I dine there one afternoon, trading bites of mushroom ragu–slicked pasta with sips of the Merkin Shinola red, a crushable, energetic Italian blend. My favorite of Keenan’s wines, though, is the full-bodied yet elegant Sancha, made from tempranillo. The Kitsuné, a sangiovese made from Willcox fruit that features flavors of sour cherry and savory herbs, is a close second.

Keenan is also busy building a new facility in the middle of Cottonwood, where he plans to eventually relocate the restaurant, consolidate winery operations, construct a large barrel room, and continue to develop vineyards. (Currently, tender vines of tempranillo, garnacha, and graciano sit atop terraces adjacent to the construction site.) It’s a huge development for this town of around 12,000 residents.

With all of these efforts, it can be easy to forget that Keenan is still a full-fledged rock star. Puscifer released a new album last year, and Tool is launching a months-long world tour in January. (As always, Keenan will be back for harvest, beginning in July.) In Arizona, though, he sees the wine industry as his legacy. What he hopes to do next is plant 80 acres of vines in the Verde Valley, so he can focus exclusively on that region. But like any great front man, as he reaches new heights, he’ll bring the rest of the band with him— in this case, by eventually selling his Willcox plot to another winemaker.

“Somebody else benefits, because now they’re getting fruit that we spent eight years cultivating,” he says. “That could be a brand that could easily exceed what we’re doing—which is great, because all ships rise.”

Get to Wine in No Time: United flies directly to Flagstaff, Phoenix, Scottsdale, and Tucson from several of its hub airports across the U.S.

Where to Stay

The Tavern Hotel

If you want to maximize a weekend of wine tasting in the Verde Valley, Cottonwood’s Tavern Hotel is set just a stone’s throw from the vineyards. The 48 rooms are simple but stylish, the hotel is surrounded by restaurants in Old Town Cottonwood, and, most important—this is Arizona, after all—there’s a pool.

From $189, thetavernhotel.com

Hacienda Del Sol Guest Ranch Resort

Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn can be counted among the celebrities who have stayed at this Tucson resort. The property, located at the base of the Santa Catalina Mountains, fits perfectly with the desert landscape—it’s worth rousing yourself to catch a sunrise—and the Southwest-style accommodations range from single king rooms to 1,100-square-foot casitas.

From $229, haciendadelsol.com

Next Up: Where to Drink Arizona Wine