The Broussaille wall on Rue du Marché au Charbon, painted in 1991, was Brussels’s first comic mural

Photography by Laura Stevens

Turning a corner on a cobblestone street brings me face to face with a towering mural featuring the likeness of a character I recognize immediately. He seems different than I recall from my childhood, perhaps because he’s larger than life now, sprung from the small comic book panels where I first encountered him. Or maybe it’s because I’m in the unfamiliar city of Brussels, where everything, even Tintin—sneaking down a fire escape with his friend Captain Haddock and dog Snowy in a freeze frame from The Calculus Affair—feels new to me.

I lift my camera to snap a photo, crouching low to capture the entire frame, and a woman walking by chuckles good-humoredly at my awkward stance. “Vous aimez Tintin? ” she asks, looking up at the mural.I mentally dig through my extremely insufficient elementary French, and nod in response. She switches to English, helpfully: “He’s one of our Belgian heroes.”

The friendly local continues on her way, and I feel a swell of kid-like zeal. As a youngster, I didn’t know many kids who read comic books, unless they were about superheroes, but the idea of sprouting wings and beaming to alien planets always seemed a tad far-fetched to me.

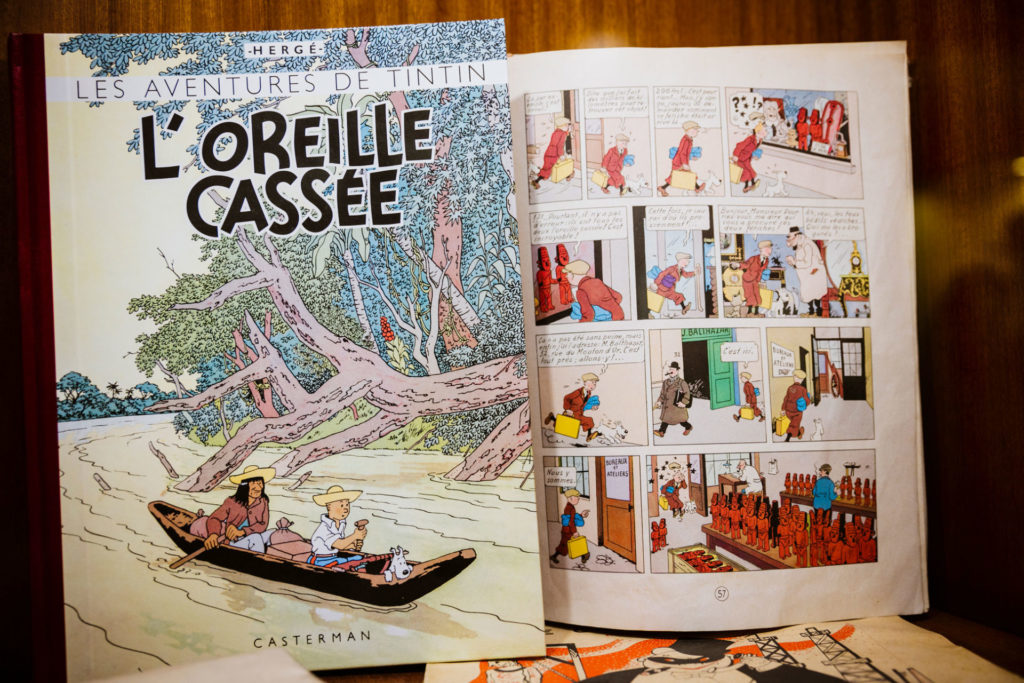

When I serendipitously discovered The Adventures of Tintin—a strip about a resourceful journalist—at the back of my neighborhood library in San Francisco, those escapades of solving mysteries and exploring different civilizations instantly captivated me. Every Saturday morning, I would sit on the carpeted floor of my bedroom reading comics, savoring the moments before I was pulled into the busyness of the weekend.

None of my friends knew the stories from Tintin—or Gaston or Willy and Wanda, my other favorites so I resigned myself to being the only one privy to these adventures.

Back then, I didn’t realize that many of the books I gravitated toward had originated in Belgium. It wasn’t until after I grew up, and had long set the strips down, that I learned comics are deeply ingrained in Belgian culture, and that a Comic Book Route in Brussels pays homage to those characters with more than 60 lovingly painted murals. For the comic-toting young girl in me, a pilgrimage was a no-brainer.

The Tintin illustration is on Rue de l’Etuve, just steps from the Manneken Pis (the famous fountain statue of a peeing boy) in one of Brussels’s most heavily trafficked areas, and it marks the starting point of my self-guided trek.

Most of the murals can be found in the Pentagon, Brussels’s city center, with a few sprinkled around the residential suburb of Laeken and the northeast Brussels area of Haren. A long my hike, I find Lucky Luke apprehending a group of bank robbers, Nero in his signature bowtie greeting some birds, and Billy the Cat jaunting along cobblestone streets that look like an extension of the one I’m walking down.

Many of the murals’ settings are designed to look like continuations of the sidewalk itself, and artistic illusions bring the comic heroes right up against reality, as they peek out of illustrated windows and climb the sides of buildings. This trompe l’oeil style somehow makes the artworks understated and eye-catching in equal measure; it’s almost as if the figures, woven into the landscape of the city, count themselves among its residents. In fact, most of them are painted on the sides of buildings rather than directly facing a main street—easy to miss if you happen to be looking down, but unmissable for those in the know.

Adrien Lobet, one of the artists currently at work on new comic murals in Brussels, tells me the pieces are designed to be a marriage between comic art and urban renewal. “The frescoes are often inspired by the neighborhood in which they are going to be painted,” he says. “It is sometimes a mix between trompe l’oeil and comics. They are made like this in order to integrate as well as possible into the urban environment.”

Lobet works with Urbana, a street art group that the city government commissioned in 2013 to reproduce comic iillustrations on building facades across town.

The organization is also restoring the Comic Book Route’s earliest frescoes, which date back to the ’90s, when they were created in part to spruce up walls left bare by the removal of promotional billboards. “The city of Brussels has waged a firm fight against large advertising posters,” he tells me. “It is in this context that the first comic-strip fresco was produced.”

As the Comic Book Route takes me farther from the city center’s main tourist attractions, I step into quieter corners of Brussels where I might not have otherwise ventured. And although I’m on my first solo trip to Europe, I hardly feel alone with such familiar characters greeting me. In fact, I feel a wave of relief. While I’d once thought that these non-superhero and sometimes non-English comics were just a strange niche interest of mine— meant for quietly harboring, not openly flaunting—I can see now that I’m part of a huge community of enthusiasts.

Another member of this community is Jan Baetens, a Belgian poet who teaches cultural studies at the University of Leuven. When I tell him that I once believed myself an outlier for enjoying these comics, he reassures me that I was not alone in feeling that way. “Comics, for many decades, were not considered culturally legitimate,” he says. “It was a form of popular culture which was discarded from official culture in most countries,” including in neighboring France, where the medium was shunned to the outskirts of the publishing landscape.“The major periphery of Francophone culture in Europe is Belgium,” he continues. “Belgian publishers, in order to stay in business, were obliged to concentrate on specific genres that were, let’s say, considered less interesting.”

Belgium, fortunately, did not develop an inferiority complex. Rather, many people here viewed the beginning of the country’s large-scale production of comics in the 1930s as an opportunity to carve out a niche that was uniquely theirs.

From the ’60s on, as the country developed its own storytelling style, Belgian comics came to be viewed as a serious and legitimate form of visual art. Even the language supports this. The French term for the genre, bandes dessinées, translates to “drawn strips” and doesn’t imply something frivolous the way the word “comics” does for some.

In fact, Belgium’s official educational system adopted the strips for language training, Baetens tells me, since the interesting images, coupled with relatively simple dialogue, are helpful for beginning readers.It shouldn’t come as a surprise that something that facilitates language learning and welcomes non-fluent readers would be embraced by this multilingual country.

Signs and menus in Brussels, I notice, are often written in both French and Dutch—which, along with German, make up Belgium’s three official languages. The nation’s many tongues are a reminder that it has served as something of a European crossroads throughout history, frequently influenced by neighboring cultures.

“Paris is the center of the French-speaking culture, and Amsterdam of the Dutch-speaking culture,” says Tine Anthoni, head of communication at the Comics Art Museum in Brussels.

“We’ve always been a smaller neighbor next to giant cultures.”

The Comics Art Museum, housed in a breathtaking Art Nouveau structure, takes visitors on a journey from the early days of European comics to the genre’s present-day developments.

Welcoming 260,000 visitors in a typical year, it honors the creators and illustrators who refined the Ninth Art (as comics are often called in Europe) into a Belgian point of pride. These artists, such as Hergé (Tintin), Morris (Lucky Luke), and Peyo (The Smurfs), pioneered the quirky surrealism for which Belgian comics came to be known.

They let their imaginations run wild but also kept their stories down to earth with an amusing element of self-deprecation. Anthoni tells me that being sandwiched between—and sometimes overshadowed by—larger countries bred a certain easygoing modesty in Belgians. “We just can’t take ourselves seriously,” she says. “It’s impossible.”

That humility lends itself to the playfulness and clever banter that became defining traits of Belgian comics. “It’s a kinder form of humor,” Baetens says, “which of course has to do with the fact that these comics were meant to be read and enjoyed by all generations.”

Indeed, comics kept the lighthearted side of the country’s identity alive, even as Brussels became the de facto capital of the European Union in 1958, which gave the city a more bureaucratic bent. Comics invited everyone—even those like me who didn’t necessarily read the language—to take part in the story.

“At the movies, you’re just a spectator,” says Frédéric Lorge, the founder and director of Brussels’s Comic Art Factory, a gallery that showcases, sells, and buys original strips.

“When you read a comic book, you’re participating. You fill in the gaps in the story and decide the time lapse between the sequences.”

Lorge is a lifelong comic zealot, and, in addition to collecting them for his gallery, he still reads them every week. Listening to him, I think back to when I became engrossed in the quests of Tintin, Spirou, Ric Hochet—all characters who happened to be reporters, and whose images now adorn the Comic Book Route.

Their story hunting transported them to places I’d never been but wanted to learn more about. It would be a romanticization to say those strips were the impetus for my working in journalism years later, but perhaps that early exposure did plant some seed of interest in exploring the world for the sake of storytelling.

The medium leaves just enough room to picture oneself in the protagonist’s shoes; I never got my hands on an English version of Ric Hochet, but my imagination did the translating for me.

Envisioning myself on these adventures wasn’t hard. Most of the characters don’t embody some unattainable, transcendent level of brilliance or strength. The seafaring Captain Haddock from The Adventures of Tintin is often short-tempered and inebriated, but his sincerity as a loyal friend is admirable, especially when his character arc sees him put down the bottle and even volunteer to sacrifice his life for Tintin.

“They were clumsy,” Lorge says. “They were making mistakes. You have the superheroes in the U.S., and it’s always good versus evil. In Belgian storytelling, there is much more gray area.” Re-examining those gray areas through the lens of adulthood can at times be troubling.

The earliest Tintin comics—Hergé’s characters first appeared in 1929—espoused far-right views and caricatured different cultures in ways that are unmistakably offensive. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets contains anti-communist propaganda, I realized upon revisiting it, while Tintin in the Congo portrays an African tribe as primitive, and also sees its star hunting big game. Hergé later changed some of the controversial images, admitting to their flaws.

It’s conflicting to see these strips in a different light. In my childhood memories, Tintin was an upholder of honor, a defender of justice. I wanted to emulate those positive qualities, but seeing the whole picture now does serve to remind me that the heroes we idolize as children are not without faults.

Today, Belgium continues to play an important role in the development of the Ninth Art. A strong community of comic artists, educators, and enthusiasts is working to keep the culture alive, with higher education institutions offering artistic training and even advanced degrees specializing in comics. A well-established network of comic book shops invites readers to dive into the stories. And, according to Lobet, in 2021 the Comic Book Route is slated to see some new frescoes unveiled. These landmarks preserve cultural heritage and bring people together—all in the spirit of childhood sentimentality and a shared love for comics.

The murals certainly transport me to my own childhood. Seeing the Smurfs mill about on the ceiling of an underpass in the Brussels Central train station (a piece that was painted in 2018 to honor the characters’ 60th birthday—although, sadly, part of it collapsed recently) arouses clear memories of diving into comics to find a familiar escape while I was transitioning to a new school.

Encountering the courageous engineer Yoko Tsuno floating through outer space, not far from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, reminds me of when my uncle gave me one of the Roger Leloup–illustrated books upon returning from a business trip. Spotting Tintin, I recall high school and staying up late to watch the Steven Spielberg–directed The Adventures of Tintin film on opening night.

These images around Brussels take me back to more innocent times, and I find comfort in learning I’m not alone in that feeling.

The community these murals were made for includes those who grew up in Belgium and also, thankfully, Americans who once read them on their bedroom floors.

Next Up: Dramatic Drams