PHOTOGRAPHY BY IRINA WERNING

For more than two decades, the image of Adolfo Cambiaso popping open a bottle of victory Champagne has been a familiar sight to polo fans the world over. Perhaps the planet’s greatest player—at the post-prime age of 42, he won the 2017 World Polo Tour’s Pro MVP award—Cambiaso has led his team, La Dolfina, to dominate the game.

La Dolfina’s record at prestigious Triple Crown championships is exemplary: Over the last five years, the team has claimed 13 of 15 tournaments, failing to reach a final just once. That string of victories has included five consecutive wins at both the Tortugas and Palermo Opens.

At the Tortugas competition in 2017, Cambiaso scored seven goals as La Dolfina flattened its nearest rival, La Ellerstina, in a one-sided final. While Cambiaso added another trophy to his mantle, one of his horses took the prize for best steed: Cuartetera B05, a sleek brown mare with a white-striped face that’s a genetic clone of the original Cuartetera, a famous retired polo horse.

Galloping to glory with a whole team of clones of one horse was the culmination of a quest with which Cambiaso has been obsessed for a decade.

Cambiaso’s use of clones is arguably more remarkable than his enduring status as world No. 1. In a development straight out of science fiction, he has gathered a crack team of scientists to revolutionize the field of horse breeding for polo, even playing the entire 2016 Tortugas final on six different Cuartetera copies—all with a brown hide and a white facial stripe.

“I felt like it was a dream come true,” Cambiaso, a Buenos Aires native, says of his 2016 feat, “and I felt like it would silence the many people who have spoken against cloning.”

Galloping to glory with a whole team of clones of one horse was the culmination of a quest with which Cambiaso has been obsessed for a decade. Working closely with a select group of collaborators, he has overcome widespread skepticism to make advancements that are transforming both science and sport.

The story originates at a fiercely contested final at the Palermo Open in 2006. When Cambiaso’s beloved stallion, Aiken Cura, had to be put down after breaking a leg, he collected a skin sample and stashed it away in a deep-freeze unit. “I don’t know why it occurred to me that cloning might work,” he recalls. “In that moment, I decided to save a few cells from a horse that was so important to me. That’s where it all began.”

The idea of cloning horses wasn’t unheard of at the time. Italian scientists had done it in 2003, and so had an American group in 2005. But no one had yet attempted to do so with high-priced polo ponies. In 2009, Cambiaso was approached by Alan Meeker, an American energy mogul and polo enthusiast who had heard the star was curious about cloning. Meeker dreamed of replicating fine steeds—both to populate his personal stable and to sell for profit—and the two men quickly clicked. They went into business, initiating attempts to clone Aiken Cura at ViaGen, a laboratory in Meeker’s native Texas that offers pet and livestock cloning services. A year later, one of their first Cuartetera foals sold for $800,000—the highest price ever paid for a polo horse—at auction in Buenos Aires, and during the 2013 polo season, Cambiaso rode Show Me, a clone of a horse named Sage.

The buyer of the record-breaking Cuartetera clone was Ernesto Gutiérrez, an Argentine businessman who told Meeker and Cambiaso they were making a mistake by selling their clones on the open market, effectively losing control of a prime asset. The pair invited Gutiérrez to become the third partner in Crestview Genetics, which opened its own laboratory in Argentina in 2010. Following a few years of false starts, Crestview established itself as a cutting-edge cloning center that now works not only for Cambiaso but for many other polo players and horse breeders, who pay about $120,000 per animal.

“With cloning, two plus two isn’t always four,” says Dr. Adrián Mutto, the molecular biologist who runs the Crestview lab, located in a bungalow on the verdant Gutiérrez estate, about an hour outside Buenos Aires. “You can make so many different mistakes—then it suddenly works. Now, we are seeing the fruits.”

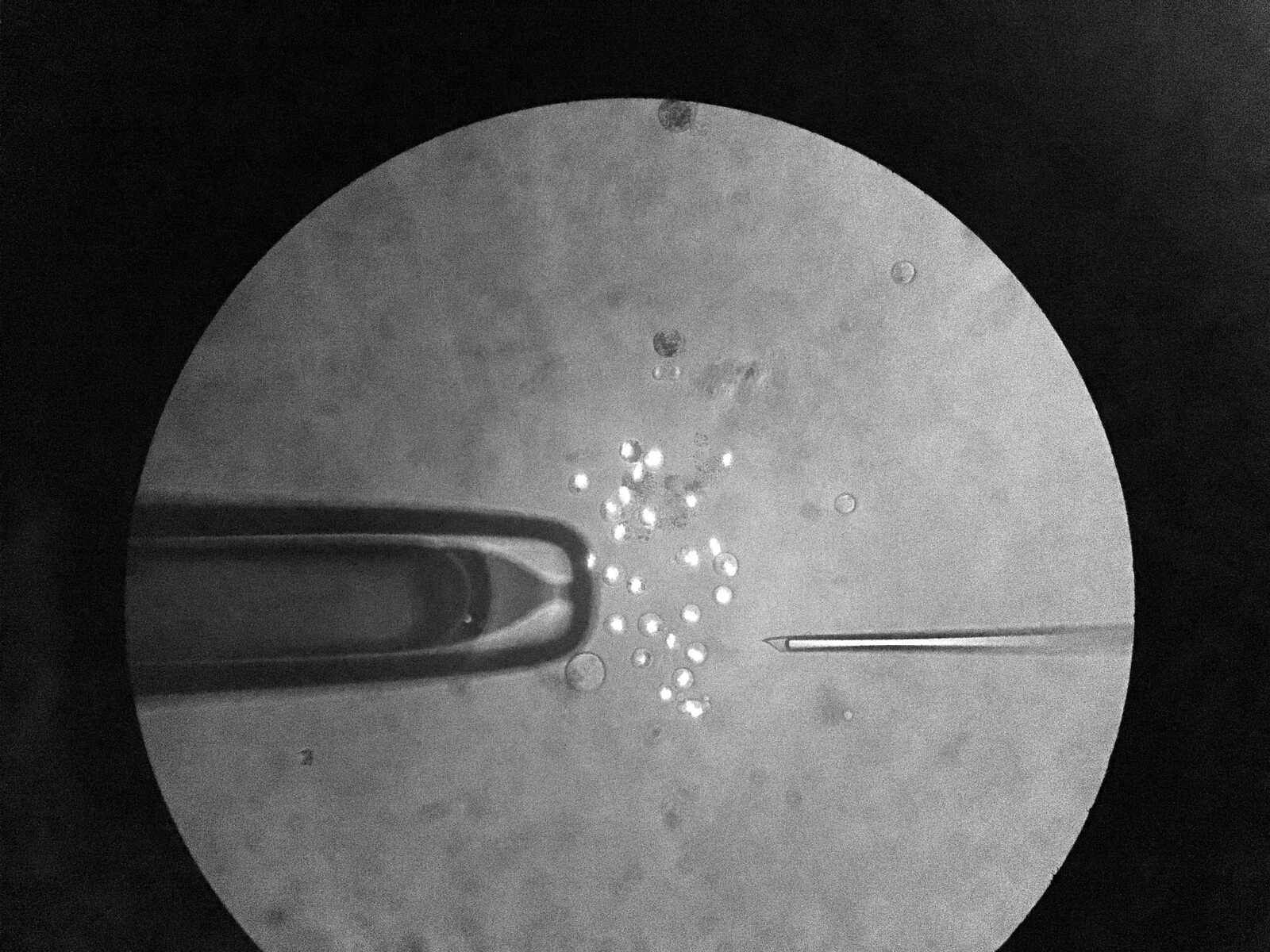

Crestview’s technique is based on somatic cell nuclear transfer, a biotechnological method that Mutto has spent more than a decade developing. To clone a horse, frozen skin cells from the donor animal are implanted in manipulated ovaries. The nucleus of each egg is removed with a microscopic syringe, the replacement DNA is inserted, and an electric shock is applied to the embryo, essentially bringing it to life.

The growth of cloning can only improve the supply of good quality ponies and, thus, the sport.

“They call me ‘the Eggsucker,’” Germán Kaiser, a lab tech at Crestview, tells me as we stand at his workstation in the dimly lit Crestview facility. As he skillfully controls a microscopic needle to remove the nucleus of an embryo, Guns N’ Roses’ “Paradise City” blasts on the stereo. “It’s like playing a PlayStation.”

After seven days, this modified embryo is implanted in a recipient mare. (Of the 200 to 300 ovaries processed in each cloning session, about a third reach this stage.) If all goes well, a clone is born 11 months later. Mutto says the lab’s pregnancy rate is between 30 and 40 percent; about one in every 10 pregnancies results in a successful birth.

“I look at a foal when it’s born and say, ‘I saw you here,’” Kaiser adds, “which is amazing, even if I don’t know which one it was.”

“I’m surprised by how innovative the polo people have been in embracing this technology,” says Dr. Daniel Salamone, a biologist at the University of Buenos Aires who was part of the first team to clone a horse of any kind in Argentina, in 2010. “In polo, it seems to have found an appropriate niche, and some players have a commercial interest. But if we start to clone all the different animals, we’ll be in trouble.” As he talks, sitting in his office at the university’s agronomy department, surrounded by a large park where goats and cows graze, he clicks through pictures of his team’s experiments, including cloned embryos of tigers, cheetahs, and leopards.

Although the current “artisanal” cloning techniques have not yet achieved mass-production capabilities, Salamone says a shrinking gene pool based on DNA from a handful of cloned animals would render negative features more prominent in their offspring. Some members of the polo community take that fear to its natural conclusion. “It could stop evolution,” says Sebastián Merlos, a polo player and horse breeder who owns one of the first polo pony clones produced in Argentina. “The fundamental thing about breeding is to improve every year, with different blood, so you make the product better. I’m not against cloning, but I’m a little scared that we might just end up with the same quality.”

Several academic studies have raised concerns about possible health hazards of the horse-cloning process, such as fetal deformation and high rates of embryonic loss. A 2016 paper by Dr. Madeleine Campbell of the Royal Veterinary College, England, stated that cloning was “ethically dubious” on health grounds and—while acknowledging a lack of comprehensive data, due to the technology’s relative infancy—called on commercial labs to provide a “stronger evidence base” by carefully documenting the medical progress of their clones.

Nonetheless, authorities in the polo world show no sign of moderating their liberal stance on the use of clones in professional competition—in stark contrast with thoroughbred racing, which prohibits the practice.

“Whereas a racehorse owner can be assured of profit from a champion’s offspring due to strict control of racing bloodstock, it has not been the same with polo ponies,” says Nicholas Colquhoun-Denvers, president of the Federation of International Polo. The practice of keeping stud books to track polo bloodlines all but disappeared long ago, thanks in part to countless horses perishing during World War I. Colquhoun-Denvers welcomes the growth of cloning because, he says, “it can only improve the supply of good quality ponies and, thus, the sport.”

Some experts even believe that using clones and training them in the same ways as the originals would decrease the adjustments in technique that riders would need to make. Crestview has taken this idea to heart: Meeker told the journal Science that his team has “narrowed as much as humanly possible the [difference] between original and the clone,” going so far as to use the same color barn blankets and dogs as the ones the donor horse knew.

For his part, Cambiaso brushes off any suggestion of evolutionary or ethical conflict over cloning. “I don’t debate very much,” he says. “I do what I feel like I need to do.” He no longer knows how many cloned ponies live in his stables, and he says that Crestview’s technology “gets better every year.” The champion Cuarteteras have quieted doubters who questioned the logic of investing so much time and money in a costly, unproven science. And now Cambiaso is continuing to pursue innovation with the same single-minded zeal he has displayed in his playing career. He is using Aiken Cura clones to father new foals that are being trained for competition, and, next, he hopes to clone “a really good racing stallion” and breed it with polo horses.

“Sometimes I’m wrong, sometimes I’m right,” he says. “I wasn’t mistaken this time, because now everyone else is doing it. History will remember that.”