When photojournalist Jaida Grey Eagle was studying at the Institute of American Indian Arts, she yearned to see more exhibitions highlighting the relationship Indigenous people have long had with photography in the United States. As one of the cocurators of In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now, a new show at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), she is doing her part to reframe the historical narrative.

When the opportunity to work on In Our Hands arose, she says, “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I can see this evolving into something that’s not only needed, but being searched for by people like me.’”

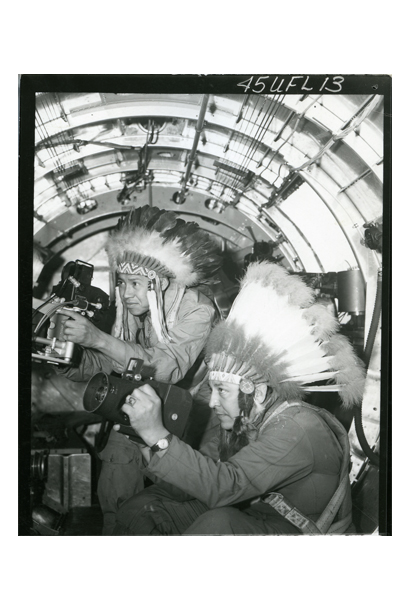

The exhibition highlights photographers who hail from First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and Native American cultures. As Casey Riley, Mia’s chair of global contemporary art and curator of photography and new media, puts it, photography by Native creators has “been undervalued by museums for a long time.”

As part of Mia’s efforts to right that wrong, the museum collaborated with a curatorial council of Native artists, scholars, and knowledge-sharers, as well as a council representing Indigenous leaders and community members.

The result is an exhibition that surveys a diverse range of photographic eras, styles, and subjects. Some images directly depict Native fortitude, such as Russel Albert Daniels’s picture of Dakota Access Pipeline security lights illuminating Standing Rock Sioux Nation tipis, or Pat Kane’s Maryann Mantla, Gameti, in which a woman in a headscarf sits with her face turned away from the camera in a pose of symbolic resistance. The latter image “is this acknowledgment of hundreds of years of Native people being photographed by non-Native people,” says Mia associate curator of Native American art Jill Ahlberg Yohe.

Other pieces explore the complexities of Indigenous identity. For example, documentary photographer Tailyr Irvine tackles the issue of blood quantum, which determines enrollment within tribal nations. Choosing who to have children with is “a huge consideration that a lot of us have to make,” says Grey Eagle, who is Oglala Lakota, “because our tribal enrollment is tied to hunting rights. It’s tied to fishing rights. It’s tied to land ownership. It’s tied to a lot of things.”

The show isn’t limited to sociopolitical questions. Many images document Native history, life, and leaders past and present; some photos are magical, mysterious, and metaphorical, such as Meryl McMaster’s On the Edge of This Immensity, in which a woman holds a boat full of ravens against a pastel sky. For Riley, the picture “speaks to the limitless creativity and imaginative power of Native photography.”

Indeed, the cocurators hope visitors leave feeling mesmerized, appreciative, and, Grey Eagle says, “inspired to trust that Native people have the agency to tell their own stories—and that they have for forever. It’s a really beautiful way of life, and it’s complicated, and it’s wonderful. I think that we could all really learn from each other.”