Hawaii is the most isolated populated landmass in the world, a fact that has turned it, somewhat paradoxically, into a cultural crossroads. The blend of influences on the islands from around the world—ranging from Native Hawaiians to Asians to continental Americans—is exactly what the Hawaii Triennial 2022 seeks to explore.

“Continental discourses often get locked into binaries, but what makes Hawaii interesting is its multiplicity of histories and perspectives beyond a binary,” says Triennial associate curator Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick, a Hawaiian artist and gallerist. “It really is an expression of multiculturalism at its best.”

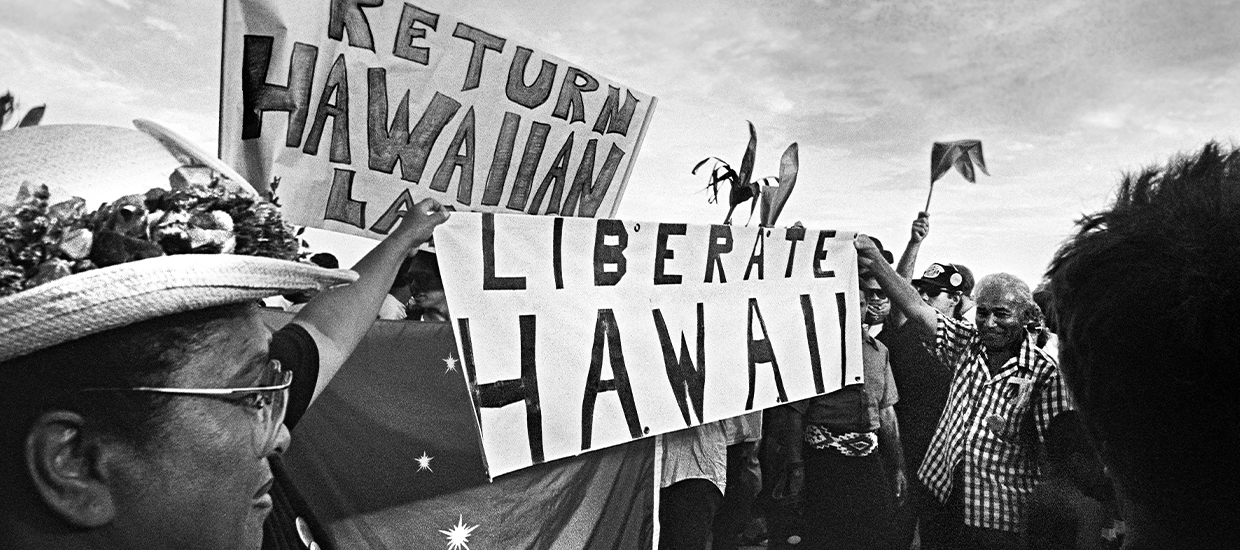

The Triennial, which is put on by the nonprofit Hawaii Contemporary, an outgrowth of the Honolulu Biennial, opened February 18 and runs through May 8 at seven institutions in the state capital (including the Bishop Museum, the Hawaii State Art Museum, and the Royal Hawaiian Center). The exposition, which is titled Pacific Century – E Ho‘omau no Moananuiākea, features works from more than 40 artists. Broderick sought to incorporate local artists who may not have received wide recognition, such as Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina (“The Eyes of the Land”), a video production team that has documented land and native rights struggles since 1981. Another associate curator, Miwako Tezuka, a New York–based specialist in Japanese art, focused on pieces that represent Hawaii’s deep connections with Japan. For example, the Honolulu Museum of Art is showing a series of images by Tokyo-born photographer Ai Iwane that traces the movements of people between the two places.

In some cases, the connections can be more conceptual than direct. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei recreated his 2010 London installation Tree—three tree sculptures, two fashioned of wood and one of iron, which function as a commentary on human intervention in the natural environment—at Honolulu’s Foster Botanical Garden. “The selection of the artists was about an idea of place, thinking about Hawaii as a cultural center, but also geographically, and why a large portion of the artists had an engagement with the Asia-Pacific [region],” says Triennial curatorial director Melissa Chiu, who is also the director of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.

The works also interact with their settings. At the Iolani Palace, for instance, California-based artist Jennifer Steinkamp created a site-specific digital installation inspired by the flower garden of Queen Lili‘uokalani, who was placed under house arrest following a U.S.-supported overthrow of the monarchy. “These places provide an additional level of meaning for the Triennial-goer,” Broderick says. “As they’re standing in front of a work of art, they can also have an understanding of where they’re literally standing on the island, what has happened there, and how that history might relate to the work they’re experiencing.”

Next Up: A Tour of the Island of Hawaii’s Powerful Volcanoes and Spiritual Sites