“Welcome to warm weather,” a baggage handler says as I exit the plane after a three-hour flight from Newark. The arrival hall at the Key West airport has two mini-carousels for luggage, a rental-car counter, and a small bar outfitted with pre-made cocktail dispensers. In the men’s room, an ad for something called the Hangover Hospital boasts, “Key West’s ONLY Doctor Run IV Service!”

Key West’s fun-in-the-sun reputation sure does precede it… but I haven’t flown in for a stumbling tour of Duval Street’s honky-tonks. Rather, I’ve come in search of something more elusive. Well, two things, really: The first is a living connection to Key West in the 1970s, a shining moment during which an artier and less commercialized party scene flourished. The second is the tarpon, a legendary game fish that many an angler dreams of hooking.

This mission is not as incongruous as it may sound. The two themes are closely related, as I learned several years ago from the obscure 1973 documentary Tarpon. Impossible to find for decades, the 50-minute film resurfaced on DVD around 15 years ago, and I sought it out because it features rare footage of two of my favorite writers, Tom McGuane and the late Jim Harrison. The film portrayed a group of artist-anglers in Key West living what some (including me) would consider the dream: drinking beers, cracking jokes, waxing philosophical about metallic-looking tarpon that soar out of the water in almost psychedelic slow motion. The gilding on the tropical art-house lily was a twangy instrumental soundtrack by Jimmy Buffett, who also lived in Key West at the time and who eventually became more famous than everyone else in the film combined.

Of that group, McGuane is the one whose life and work I admire most. He arrived in Key West in the late 1960s and began penning saltwater fishing stories for Sports Illustrated, much as Ernest Hemingway had done for Esquire decades before. It was here that McGuane wrote his breakout novel, Ninety-Two in the Shade, a tale of feuding fishing guides that beautifully captured the intergenerational frictions of the era and earned him the moniker “the hippie Hemingway.”

McGuane helped spread the word about the island’s superb fishery and anything-goes nightlife; soon, counter-culture figures such as Harrison, the poet Richard Brautigan, and the painter Russell Chatham were showing up on fishing trips. The watering hole of choice for this wild bunch—possibly the most talented gang of creative sportsmen ever assembled—was the pocket-size Chart Room, where a 20-something Buffett (who hadn’t yet caught the fishing bug) performed for drinks.

I was surprised to learn, while planning my trip, that the Chart Room is still around. What’s more, it’s almost totally unchanged—still tiny (barely wide enough for two pickup trucks) and still tucked inside the several-times-expanded Pier House Resort & Spa. Upon arriving, I enter to find the walls and ceiling plastered with old party photos, boat flags, nautical charts, and dollar bills. I’m a few sips into my first daiquiri when a wedding group in polo shirts and sundresses bursts in, orders a round, and then leaves just as suddenly as it entered. When calm is restored, I strike up a conversation with the bearded young bartender. Pretty typical crowd for an April weeknight, he tells me. When I brag that I’m about to go fishing with a guy who tended bar at the Chart Room in the ’70s, he doesn’t believe me.

The next morning, I do, in fact, meet up with Chris Robinson, a lean strip of leather with a white ponytail, upturned white mustache, and sun-scabbed legs poking out from old khaki shorts. We motor out from the Cudjoe Gardens Marina on Cudjoe Key (the boat ramp at Key West got too busy years ago, Robinson rasps through fried vocal chords) and into the intercoastal waters of the Great White Heron National Wildlife Refuge, a 200,000-acre aquatic back-country that’s low on boat traffic and awash in cool blues and lush greens.

Robinson cuts the motor, mounts the poling platform at the rear of his skiff—no mean feat for a 76-year-old—and starts scanning the water for bonefish, the silvery bottom feeders that rocket across the white-sand flats when hooked. The mangroves are alive with squawking cormorants; gliding rays and lemon sharks patrol the shallows. Bonefish are smaller and easier to catch than tarpon, and a nice warm-up for the main act. Neither Robinson nor I spot any of them, though, so he entertains me with memories of ’70s Key West instead. There were naked boat rides, two-hour lunch breaks at the Pier House pool, Hunter S. Thompson roaring around in a Buick convertible while barking out nonsense commands through a bullhorn. Robinson tells me he taught the famously erratic Thompson how to use a motorboat. “That was scary,” he says with a chuckle.

Robinson was Jimmy Buffett’s downstairs neighbor in those days, and after we say goodbye—following a disconcertingly slow day of fishing—I drive back to Key West for a look at the clapboard apartment building they once shared. It’s now part of the three-star Coconut Beach Resort, but it’s next door to a ’70s mainstay that has survived: Louie’s Backyard.

Around the side of Louie’s I find the restaurant’s easygoing Afterdeck Bar. The sea breeze rustles the palm trees, and the Atlantic laps at the shore beneath the patio. There’s a golden-hour magic in the balmy air, as though the day is letting out a deep sigh. Hemingway was known to start drinking in the afternoon and get to bed early, so he could start writing early the next morning. It occurs to me that when the daylight hours are this wonderful, any schedule that maximizes them is a sensible one.

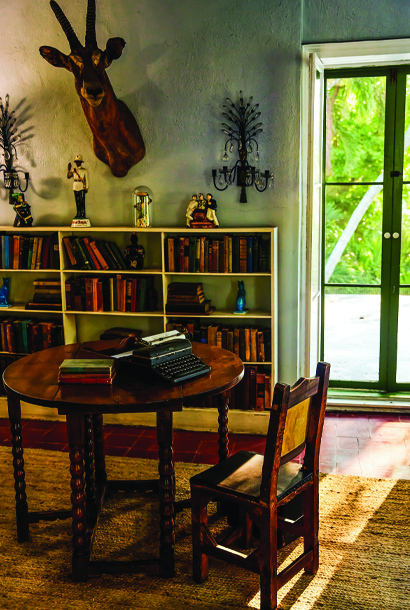

Speaking of Papa, the following day I visit the Hemingway Home & Museum, a Spanish Colonial mansion in which the author lived with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, from 1931 to 1939. Hemingway could be a boorish depressive, but the nicely preserved house—with its famed resident cats, palm-shaded backyard, trophy-stuffed writing office, and old shelves jammed with early editions of famous works—exudes an aura of writerly solitude and exotic adventure. I would think that the climate and the fishing would get in the way of work, but Hemingway’s Key West period was among his most productive.

Later, I visit another place owned by a local light: Margaritaville Beach House Key West, a recent addition to the business empire that has reportedly made Jimmy Buffett a billionaire. My companion is Carol Shaughnessy, a writer and publicist who came to the tropics from Minnesota in 1976 and once worked for Buffett. “Is Margaritaville a real place?” she says. “No. But if it were, it would be here in Key West, which was the cradle of Jimmy’s creativity. It was where he became Jimmy Buffett.”

Shaughnessy helped open the first Margaritaville T-shirt shop on Margaret Street in 1985 and was the original editor of Buffett’s mail-order newsletter. “We weren’t selling T-shirts,” she says; “we were selling a lifestyle.” Millions of Americans have since bought into that lifestyle, one of the reasons why the unpackaged Key West of the ’70s seems so distant now. Yet Shaughnessy, who has fond memories of dancing barefoot in the Old Town streets and dating the smuggler who inspired Buffet’s “A Pirate Looks at Forty,” insists that the broad appeal of the place is part of what continues to make it special. “People are where they’ve chosen to be, leading lives they’ve chosen to live,” she says. “That’s why everyone here is so friendly.” As we leave, I notice our Jamaican waitress is dancing with another patron. I can see Shaughnessy’s point—they both seem to be having a great time.

Now let’s get back to the thing that brought my literary heroes and me here in the first place. Many people think of fly-fishing as meditative; saltwater fly-fishing isn’t that. It’s more like hunting than the freshwater version of the sport, with fish that tend to be bigger and more powerful—not to mention on the move. Whereas fly-casting into a pond or river can feel like shooting free throws, here it’s like completing a pass to a zig-zagging receiver, often with just one chance to get it right. It’s aggravating, and it’s also addictive.

Finding a tarpon can take hours of intensive searching, and even after you’ve located your quarry, so many things can go wrong. The guide must quietly position the boat just so. The wind might kick up, or coils of fly line might get tangled in your feet. One bungled cast usually means game over—and all these worries arise before you even have a fish on. Tarpon have bony lower jaws and great leaping abilities, meaning they’re adept at both spitting hooks and snapping lines. Are they as powerful as marlin, which require grown men to strap themselves into bolted-down chairs to avoid being hauled overboard? Well, no; a big marlin weighs nearly half a ton, whereas the heaviest tarpon ever caught on a fly was just above 200 pounds. But the skill involved in hooking and fighting a tarpon on light tackle—in addition to the fact that you often get to watch them take the fly in shallow water—have convinced many a well-traveled angler that they are the most exciting game fish on the planet.

The guide I hope will bring me to my first tarpon is Will Benson, who at 43 is just a year older than I am but is connected to the glory days by his parents, who moved here in the ’70s. Even at $800 a day, he’s much in demand, and I’m optimistic we’ll have a great day of fishing and reminiscing.

It’s already T-shirt weather when we meet at 8 a.m. at Lower Sugarloaf Key, a 25-minute drive from Key West. As we head out into the backcountry, beneath blue skies and sparse white clouds, Benson calmly scans the water of a mangrove-enclosed channel. We emerge into a stretch that is shallow enough for me to see down to the turtle grass and tire-shaped loggerhead sponges at the bottom.

An angler aboard a distant skiff is casting to rolling tarpon; I can just make out their dorsal fins sliding in and out of the water. Benson watches in silence for two or three minutes. “They didn’t like that last cast,” he mutters. From several hundred feet away, he has picked up a shift in the school’s behavior that has completely eluded me.

It would be a breach of etiquette to barge in, and the tarpon have moved on anyway, so we look elsewhere. Later that morning, at a spot that’s within view of Route 1, I get my first proper look at one—a six-foot-long torpedo that advances with unsettling quickness, even though its fins and tail seem spookily motionless. At Benson’s direction, I cast the fly in front of it, jam the rod under my armpit, and begin quickly stripping the fly in using both hands.

The tarpon ignores it. Sometimes that’s just what happens, my guide explains, but sometimes an angler’s anxious movements put them off. This is the cruel irony of tarpon fishing: Right at the tensest, most anticipatory moment, it is imperative that you settle your nerves. “You got a bit of the jitters,” Benson says. “That’s normal.”

To take some of the pressure off, we discuss the film Tarpon. Benson loves the obscure doc as much as I do, if not more: He says it inspired him to try his hand at filmmaking. He tells me he cherishes it as a portrait of “a magical place and time”—and of a group that pioneered a do-less-harm approach to tarpon fishing. While other anglers were competing in tournaments and hauling carcasses off to the weigh station, McGuane’s crew were admiring the sheer beauty of the leaping tarpon and releasing their catches back into the water. “By just doing their thing, they landed on this new mentality that was way ahead of their time,” Benson marvels. The sport is less bloody now as a result.

On the flip side, there are more anglers on the water nowadays, and fewer fish, which has left Benson trying to get ahead of the next conservation curve himself. He refuses to endanger tarpon for the sake of an Instagram photo and advises clients to fight them faster, so as to avoid exhausting them or turning them into shark food.

He also urges his clients to appreciate simply being lucky enough to hook one of these majestic creatures and watch it jump, and to treat any additional action as a bonus. I know for a fact that this is a tough sell for some sport fishermen, but it’s of a piece with the advocacy work that Benson does for the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, a model conservation organization based in South Florida. I believe him when he says that if nothing is done about the upsurge in anglers engaged in social media–fueled competition, the tarpon fishery of the Lower Keys is headed for serious trouble. (That’s not the only threat, either: A recent study cosponsored by BTT and Florida International University found worrying levels of pharmaceutical contaminants in Florida game fish.)

After a fruitless 90 minutes on the ocean side of the highway—a mere “trickle” of tarpon, Benson complains—we cross back over to the bay side. He opens the throttle of his baby blue Chittum, the Ferrari of flats skiffs, and we rip along at upward of 60 miles an hour. “At the end of the day, fishing is an excuse to go on a nice boat ride,” he muses once the roar of the engine has died down. I recognize this as a guide’s tactful way of getting his client to accept a skunking.

Soon, though, I’m startled by the close-range sighting of a tarpon, which fixes a primeval eye on me, flashes its emerald back … and rejects my fly. Minutes later, another one comes bearing down on us from 12 o’clock. The requisite 40-foot straight-ahead cast is not a difficult one. I strip the line once or twice, and Benson says something I haven’t heard all day: “He took it.” Two seconds seem to pass, though he assures me afterward that it was “more like point-two seconds.” Then my slack line begins racing out, and a scaled chrome slab hurls itself clear of the water surprisingly far away. It thrashes once in midair, and before I know what’s happened the line has gone limp again. The fish has broken off.

I did a couple of technical things wrong, which I’ll dwell on later, but Benson grins and gives me a fist bump. “That’s what we’re here for!” he exclaims. “Also, that was a tank—a hundred pounds at least.” Speechless, I think back to a scene in Tarpon in which Brautigan describes the sensation I’ve just felt as “immediate unreality.” There is no better way of saying it.

The bohemian scene portrayed in that documentary has mostly drained out of Key West. It’s not a surprise—after all, most of the personalities who defined that era have died or moved on, including McGuane, who left in the late ’70s. Yet, as Benson points out, the ecosystem that brought those characters here remains a reality.

“The real magic of the Keys back then was only partly the people,” he says. “It was really about the islands, the fish; they’re the heart and soul of the Keys. They’ve been here before and are going to be hereafter.”

As long as they (and I) are around, I’d like to enjoy those islands—in pursuit of those legendary fish.

Darrell Hartman is the author of Battle of Ink and Ice: A Sensational Story of News Barons, North Pole Explorers, and the Making of Modern Media (Viking).