Perched on the southwesternmost edge of the continent, Cape Town can feel like the tip of the African iceberg—and many visitors don’t realize how much depth lies beneath the surface. They sunbathe on its beaches, cage-dive with its great white sharks, summit its skyline-defining Table Mountain by cableway, skirt its rocky coastline on cliffside drives, sip its wine—but do they ever truly engage with its people?

Now, 25 years after the end of apartheid, a new generation of creative Capetonians is hoping to change all that, as it demands to be seen and heard for the first time. Formerly ignored Xhosa and Cape Malay cuisines are going fine-dining; African contemporary art has finally gotten a museum that feels as vital as the Guggenheim or Centre Pompidou; and even the townships are embracing their status as creative entrepreneurial hubs. As Cape Town begins to shake off its colonial-era clichés and tell its own story, there’s never been a better time to visit, slow down, and listen.

Day 1

Motorcycle sidecars, penguin colonies, and prodigious plant life

It’s easy to start the morning with a positive outlook when you wake up at the Belmond Mount Nelson. Opened in 1899 as a luxury palace for ocean liner passengers, the tranquil old garden estate sits tucked down a long lane lined with 57 Canary Island date palms, across from the city center’s historic Company’s Garden. The building was painted a cheerful pink 101 years ago last month to mark the end of World War I. Churchill once called the place “a most excellent and well-appointed establishment which may be thoroughly appreciated after a sea voyage.” It works with air voyages, too.

Today, to help me squeeze in as much of the region’s dramatic scenery as possible, the hotel has arranged a half-day tour with Cape Sidecar Adventures, which offers rides on a fleet of ’50s and ’60s motorcycles. Or, if you’re like me and the thought of navigating cliffside byways on the “wrong” side of the road gives you hives, you can stick to the comfort of a sidecar.

Owner Tim Clarke outfits me in a leather jacket, helmet, goggles, and gloves and introduces me to the company’s “marketing manager”: a rescue mutt named Brody who wears “doggles.” Brody and I hop into the tandem sidecar. I’m avowedly not a dog person, but it’s can’t-fight-this-feeling-anymore cute when he rests his head on my shoulder throughout the drive.

In the fishing village of Hout Bay, we wait for the coastal fog to lift inside Bay Harbour Market. I drink a red latte, made with rooibos “tea”—actually a scrubby bush that grows in the Western Cape—and then protein-load on the country’s twin favorite snacks: biltong (dried, cured meat) and droëwors (dried sausage). On our way out of town, Brody gets in a barking match with a fur seal sitting up on the dock. People walking down the street grin and flail their arms like kids as we pass. I wave back, and Clarke shouts over the motor, pointing at Brody, “They’re not smiling at you!”

We zigzag along the scenic paths south of the city center on the Cape Peninsula—the jutting landmass that ends in the famed Cape of Good Hope, the continent’s southwesternmost point. As we hug the cliffs on snaking Chapman’s Peak Drive, I keep my eyes peeled for breaching right whales or the fins of great white sharks. No such luck.

Our next stop is the one I’m most excited about: the penguin colony at Boulders Beach. “We used to take our kids to swim with them,” Clarke tells me, as we turn into Simon’s Town, passing shops filled with penguin souvenirs. He drops me off, and I make my way down a long boardwalk to the beach, where dozens of penguins squawk, waddle, burrow, and roll around in the surf as if they’re reenacting From Here to Eternity. Tourists huddle in a giant clump, oohing and aahing at fluffy chicks and wildly snapping photos. It feels a bit like the Mona Lisa room at the Louvre, if the Mona Lisa room at the Louvre smelled vaguely of dead fish, but it’s impossible not to be swept up in the scene.

After the tour ends, I grab a rideshare to Woodstock, a burgeoning but still scrappy neighborhood where factories are being converted into galleries and high-end restaurants and the walls of buildings burst with vibrant street art. At the Old Biscuit Mill, a 19th-century red-brick factory that’s now filled with galleries and boutiques, I ride an elevator up to The Pot Luck Club, Luke Dale Roberts’s fun-loving sister restaurant to The Test Kitchen (Africa’s only entry on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list) downstairs. Up here, with outlandish views toward flat-topped Table Mountain, I order a Thai green curry martini and chef Jason Kosmas’s springbok antelope loin (when in Africa…) with fermented black beans and vermicelli rice noodles, plus deboned lamb ribs with Willy Wonka–ish tomatoes infused with pomegranate juice.

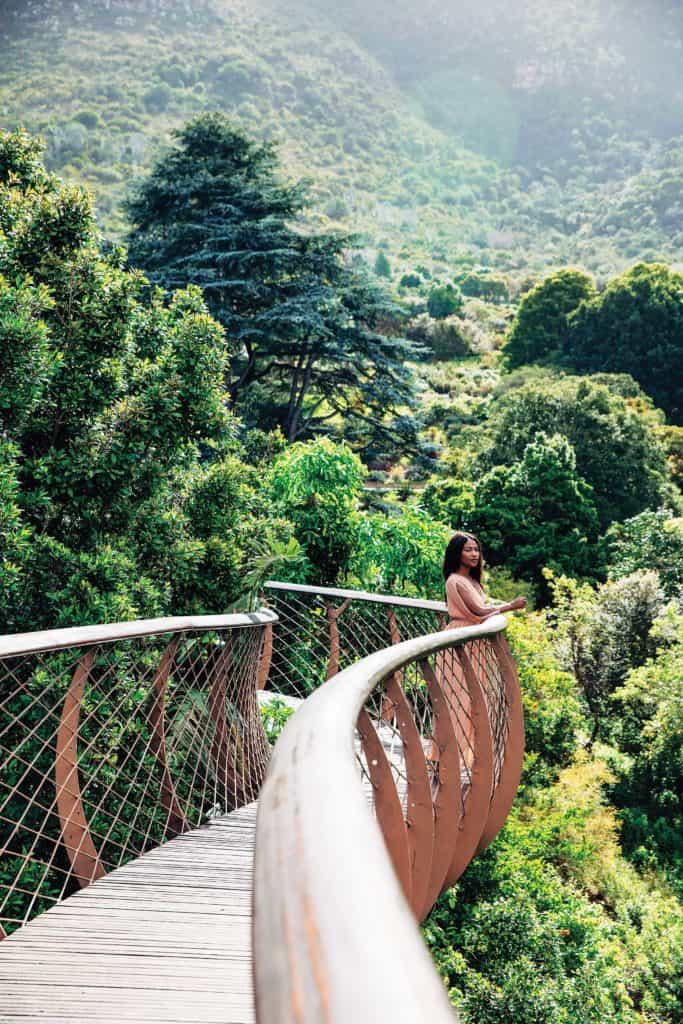

I want to work off that hearty lunch outdoors. While many visitors ascend Table Mountain by cable car, I’m looking to get a little more immersed, so I head to Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, at the mountain’s eastern foot. South Africa’s plants don’t get equal billing with its lions and elephants and giraffes, but this mountain has more botanical diversity than the entire United Kingdom. Around town, you’ll hear people talk about the fynbos, the scrubby, hardy vegetation that grows in these parts. The Cape Floristic Kingdom is one of the planet’s six plant kingdoms, stretching in a 2.7 million-acre belt; when you consider that another of those kingdoms occupies nearly all of North America, Central Asia, and Europe, you understand just how special this smaller-than-Connecticut patch is.

In the park, I track mongoose, chubby guinea fowl, and partridge-like Cape francolins, and then climb onto a wooden platform that snakes over the canopy. Back down on land, I marvel at the wild varieties of indigenous proteas, flowering plants that look like Seussian artichokes (and that gave their name to the national cricket team). Succulent-loving millennials would be obsessed.

For dinner, I head back downtown to meet chef Ash Heeger, South Africa’s representative on Netflix’s The Final Table. Her restaurant, Riverine Rabbit, is named for a highly endangered species of rabbit (“They’re just not good at breeding, unlike other rabbits!”) from the Karoo Desert.

“In terms of culture, we don’t have a very defined identity,” Heeger says, as she sends a parade of small plates, including chickpea curry pani puri and croquettes made from eel-like kingklip, to my seat at the kitchen-adjacent chef’s table. “We’re quite a young country with a sketchy past, so I take influence from all the places I’ve worked.”

She works particular magic with meat, such as seared kudu (yes, another antelope) loin with red cabbage, or braised lamb belly. “We have the best lamb in the world,” Heeger says. “The fodder in the Karoo is hard, dry fynbos shrubs with aromatic oils. You can’t compare it to Welsh lamb; you just bang it on the fire.” In a sense it comes premarinated, from the inside out.

In an attempt to do the same to myself, I slip down the road for a nightcap at The House of Machines, a café and bike shop by day, music venue and bar by night. I order a Blou Baadjie (Blue Blazer), which is basically a hot toddy made with rum and rooibos. The bartender heats the drink over a butane burner and then lights it on fire, pouring the blue flaming liquid back and forth between two pitchers until it cools—just the kind of pyrotechnics I’m looking for on my first night on a new continent.

Day 2

Touring the townships and tasting Xhosa and Cape Malay cuisine

This morning, I’m moving my bags to the One&Only Cape Town, a glitzy resort in the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront, Cape Town’s answer to Fisherman’s Wharf. Everything in this part of town is forward-thinking and shiny—see the stadium, which was built for the 2010 FIFA World Cup—but history is never far away. At check-in, I’m warned about the ear-splitting noon gun, one of two Dutch naval cannons atop Signal Hill that have taken turns firing six times a week (minus Sundays, public holidays, and a few rare exceptions) since 1806. I put a literal trigger warning in my phone.

My goal for today is to do a deep dive into the city’s townships, formerly segregated neighborhoods that are a lasting reminder of the apartheid era. Some 60 percent of Capetonians make their homes in townships or other informal settlements. Despite a reputation for crime, these areas are hotbeds of creativity. The tour company Coffeebeans Routes and its City Futures itinerary come highly recommended, and in the Gardens area of downtown, I meet guide Keith Sparks.

“City Futures was born out of something unpalatable—what was generally known as a township tour,” Sparks says as we drive east, past the orderly grid of downtown. “I used to see these buses pull up on the highway, and people would jump out and take photos at the fence. It was almost like a zoo experience.” This tour, on the other hand, is based on the idea that the city’s entrepreneurial future lies here, in a former tourist no-go zone.

In Langa, the region’s oldest township, British-Jamaican social impresario Tony Elvin—who moved here to open a restaurant with Jamie Oliver and decided to stay—welcomes us to iKhaya le Langa NPC, his arts hub and business incubator, which houses some 106 enterprises, from artists to jewelers to hot-sauce makers.

“Cape Town is a very Eurocentric city, but apart from Robben Island, the black narrative is all a bit negative,” Elvin says, as he leads me into the complex’s Sun Diner—probably the only café in the city where customers can pay with cryptocurrency. “They say don’t go to the townships, but Langa is a gateway into another Cape Town that’s bubbling up. We’re calling Langa the new city center—the Afrocentric heart of the city.”

Sparks and I say goodbye to Elvin and head back out onto the highway, toward Khayelitsha, which he compares to Johannesburg’s city-size township, Soweto. We drive past people braaiing (barbecuing) fragrant meats outside colorful corrugated tin houses and pull into a school parking lot to meet gardener Athi Ndulula of iKhaya Kulture Garden.

“iKhaya means home, so I want you to feel at home,” Ndulula says as he ushers us past living walls and soil-filled tires. “We’re using decolonized indigenous gardening methods. We wanted to show the youth what they can do with minimal space.” We sample crisp dune spinach, naartjie (a citrus fruit), and spekboom, a lemony succulent that’s 10 times as good as the Amazon rainforest at removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Before I leave, Ndulula tells me to check out his side gig: He’s an aspiring rapper who goes by Artist-X_7784. “People think the ‘X’ is for Malcolm X,

but it’s just for my mother tongue, Xhosa,” he says. “I’m just an average Joe with a garden in the ghetto!”

All that nibbling has stoked my appetite, so I thank Sparks and depart for chef Abigail Mbalo-Mokoena’s place in Khayelitsha, 4Roomed The Restaurant. A former dental technician and home cook, Mbalo-Mokoena applied for MasterChef South Africa when her family “tired of being guinea pigs.” She didn’t win, but she’s getting the last laugh: This year, Food & Wine and Travel + Leisure jointly named 4Roomed one of the world’s 30 best restaurants. She greets me warmly, dressed in a T-shirt that says “Africa Your Time is Now” and sporting one large African continent–shaped earring. “We love heavy spice,” she says, as she serves Xhosa-inspired dishes: isonka samanzi (steamed bread), umqa (pap with butternut and truffle oil), sous vide beef, and samp (mashed corn kernels) and beans, reportedly Nelson Mandela’s favorite food. Her take, made with hominy, tarragon, and coconut cream, tastes so good I wish I had a Xhosa grandma to cook it for me back home.

“My dental profession was a ticket out of the ’hood, but [people leaving] was depriving the area of black professionals,” she says. “We were not playing our role. I needed a purpose, and my purpose was to move back to the townships—to use food to bring people together.”

I tell Mbalo-Mokoena she should run for office (I mean it!), and then I take a car back to the Waterfront. I stroll through The Watershed market to stock up on souvenirs: sleek ostrich-eggshell jewelry for my sister’s birthday and a small herd of animal figurines carved from upcycled flip-flops found on the beach.

Nearby, I stop into the experimental Cause Effect Cocktail Kitchen and Cape Brandy Bar. Before I can open the menu, bar manager Justin Shaw is pouring me a South African brandy. It’s Cognac-smooth, although it was born of necessity: Apartheid-era sanctions limited booze from abroad, so South Africans crafted their own spirits. “People here grew up drinking brandy and Coke,” Shaw says. “It’s our duty to retell the story of brandy in a non-pretentious way. It’s hard for many to understand the heritage, the romance, the prestige.”

Brandy isn’t the only local product on the menu. Baskets of botanicals that guests can use for custom infusions hang over the bar. “Fynbos has been a part of the food culture here from before the Ice Age,” Shaw says, “before the settlers arrived, before the Central African Bantu arrived.” He hands me some dried mopane worms to munch on, as if I’m Timon or Pumbaa. I’m happy to have a hot, spiced negroni—made with fynbos-infused gin and vermouth—to wash those suckers down.

Dinner is a quick car ride away, in bustling Green Point, at chef Andre Hill’s Upper Bloem. The restaurant takes its name from the street where he grew up in nearby Bo-Kaap, an area that’s known for its crayon-box houses and for being the historic heart of the Muslim-majority Cape Malay population.

“This is the first time I’m cooking food that I grew up with,” Hill says. “Because of the way South Africa was segregated, this type of food was irrelevant. The majority of the population couldn’t even sit in restaurants like this.” He takes humble dishes and remixes them into clever small plates. Bunny chow—a gut-busting Durban-born fast food comprised of a hollowed-out loaf of bread overflowing with curry—is reborn as an ostrich-filled dumpling, topped with buffalo fromage blanc and shallot crumbs. His version of samp and beans is gussied up with Saldanha mussels and coconut curry. And the roti recipe? “We stole it off my mom,” Hill says with a laugh. “Food like this being recognized teaches everyone in the kitchen that your history and background are relevant. It’s not about me, it’s about the history of Cape Town.”

Cape Town is better known for its marine wildlife (like great white sharks) than its big land game, so if you feel that your trip to Africa won’t be complete without a safari, you’ll want to head east. A three-hour drive into the arid Little Karoo brings you to the private Sanbona Wildlife Reserve—which, at 224 square miles, is bigger than Guam. Of its four lodging options, perhaps the most exciting is Dwyka Tented Lodge, a nine-suite glamping enclave with outdoor showers and hot tubs set in a horseshoe-shaped ravine. Morning and evening game drives mean you’ll catch the local fauna at its most active. Try to keep your pulse from quickening when you’re arm’s-length from an elephant or giraffe, facing down a crash of rhinos (from the safety of your Land Cruiser, of course), or drinking sundowner brandies on plains that are home to lions and cheetahs. History buffs should ask their guides to show them the reserve’s 3,500-year-old San rock art paintings. From $468; includes meals, game drives, guided wilderness walks, and nonalcoholic beverages; sanbona.com

Day 3

Contemporary architecture and the world’s poshest farm

I awake at the One&Only, and though the views of Table Mountain from my balcony are bracing, I need something stronger to start my day. I wander 10 minutes to Jason Bakery for an espresso and a lamb kofta sausage roll, and then continue to the Waterfront’s Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (MOCAA), which opened in 2017. Architect Thomas Heatherwick converted a 1921 grain silo, carving out the walls of its 42 concrete cylinders, creating an atrium run through with curves, ovals, and parabolas.

I join a tour with a beret-wearing guide, Siseko Maweyi. “I was always taught to crave aesthetic symmetry, but none of these spaces are perfect,” he says, as I try to fit the cathedral-like interior into my phone’s camera frame. “Many people compared this building to Gaudí, but where that was intentional, here it happened organically.”

Maweyi points up to a 51-by-82-foot wall hanging by Ghana’s El Anatsui. What looks like a luxurious textile is made from valueless scraps of copper wire and smashed bottle caps. “It confronts notions of consumerism and waste,” he says. “It’s almost an abstract world map—it speaks to histories of spice routes, trade routes, slave routes.”

Maweyi points up to a 51-by-82-foot wall hanging by Ghana’s El Anatsui. What looks like a luxurious textile is made from valueless scraps of copper wire and smashed bottle caps. “It confronts notions of consumerism and waste,” he says. “It’s almost an abstract world map—it speaks to histories of spice routes, trade routes, slave routes.”

I pick up a rental car and drive south for an extravagant meal at La Colombe, a fine-dining restaurant on a hilltop at the Silvermist Organic Wine Estate, in the wine-growing suburb of Constantia. There’s a theatricality to the proceedings here. Upon arrival, I forage for a calamansi juice–filled white chocolate egg in an underbrush-covered log. Later, I cut open a charred passion fruit with bird-shaped scissors to reveal a stew of mussels and smoked snoek fish. Yellowfin tuna comes to the table inside a closed tin, with guacamole, citrus foam, and tiger’s milk espuma. Even the simple bread course is an event: Wagyu beef-fat butter, smoked oxtail jus, and bone marrow are heated tableside in a little copper pot and served with dippable sweet potato pain d’epi. It’s a baroque, over-the-top meal, but there’s one bite that I’ll remember for years: a simple foie gras mousse with springbok tartare on a paper-thin wafer. Is any other country, I wonder, so comfortable eating its national mascot?

It’s early afternoon by the time I’m done, and my next and final stop is about 45 minutes outside of the city: an exceedingly peaceful retreat called Babylonstoren, near the Franschhoek Valley, a wine region and onetime French Huguenot haven. Born in the 1600s as a Cape Dutch farm, the estate takes its name from a pyramidal hill on the property that reminded early

settlers of the Tower of Babel. (If you recall the story from the Book of Genesis, it’s a particularly apt allusion, given that this country has 11 official languages.)

I drive through miles and miles of vineyard, braking hard once or twice to let baboons cross the road, and pull into the 500-acre wonderland, which looks a bit like a theme park Martha Stewart would create if she were given a blank check. I drop my bags off at my cottage and head out to explore the grounds on a complimentary bicycle, seeing orchards filled with stone fruits and citrus fruits, ripe for picking; olive groves, from which fruit is cold-pressed into extra virgin oil; a chamomile lawn for ultra-relaxing naps in the sun; human-size bird nests, perfect for curling up with a book; and a veritable zoo’s worth of turkeys, chickens, ducks, geese, bees, and hammy donkeys that run to the fence for behind-ear scritches.

Before I know it, it’s dinner-time. The hotel’s Bakery Restaurant is hosting its weekly Carnivore Evening, a communal five-course feast featuring the meat from Babylonstoren-reared Chianina cattle—the breed that becomes bistecca alla fiorentina—and pairings with wines made on the farm. As the staff serves family-style boerewors (coriander-spiced sausages), chargrilled biltong, and dry-aged cuts cooked over hot coals, a duo sits to the side playing Afrikaner folk music on guitar and accordion. The wine is flowing, and a tipsy mom at the end of the table accidentally AirDrops me her photos of the Boulders Beach penguins. “They’re the best!” I shout. Waiters and waitresses begin grabbing guests and twirling them around between the tables. It feels as if I’ve stumbled into a 19th-century Boer harvest festival.

On the walk back to my cottage, I’m literally starstruck by how dazzling the constellations and the Milky Way are out here, miles from the city lights. I think of the song “Under African Skies” from my all-time favorite album, Paul Simon’s Graceland. And Toto’s “Africa.” And generations of American novelists and film directors and, more recently, social media influencers who come here and talk about how South Africa has forever changed them. I may not be willing to let myself indulge in those clichés, but I have to admit there’s something immensely special and satisfying about being welcomed into the South African family—if only for a night.

Next Up: Three Perfect Days in Puerto Vallarta