If your image of Oregon’s largest city is stuck in the Portlandia days, you’ve missed out on a decade of growth and development. Sure, you’ll still find plenty of hipster stereotypes in these parts—the bearded dudes in flannel swigging hazy IPAs, the urban farmers giving away excess eggs from their backyard chickens, the Wiccan priestesses shopping at feminist bookstores. But you’ll also meet game-changing Black winemakers, nostalgia-fueled Mexican and Southeast Asian chefs, and creative entrepreneurs reimagining rural warehouses. The pandemic has not been kind to many U.S. cities, and Portland’s downtown, in particular, became a symbol of social upheaval in 2020. Tourists have been slow to return, but while you’ve been away, the City of Roses has blossomed into something even more interesting than it was before, with a new crop of diverse business owners ready to welcome you back with open arms.

Day 1

A mellow hike on Mount Tabor, the maker scene, and next-level Mexican food

On my first day in Portland, I awake at the Kex Hotel, although I could be forgiven for feeling as if I’m somewhere much farther away. Occupying a 1912 apartment block near the eastern end of the Burnside Bridge, it’s the second location of a stylish Icelandic hotel that takes its name from the Icelandic word for “biscuit” (the original Reykjavík spot is in a renovated cookie factory), and the new place screams Nordic–meets–Pacific Northwest, thanks to its reclaimed Douglas fir floorboards and Geysír wool throws. I’m a sucker for wallpaper, so before I head out for the day, I stop in the hallway to snap a few photos of the whimsical design by local tattoo artist Melanie Nead; the pattern combines natural elements found in both Iceland and Oregon, including puffins, lupines, and volcanoes.

Speaking of which, my brunch plans take me to Montavilla, an up-and-coming neighborhood in the shadow of Mount Tabor, an extinct volcano turned city park. In fact, the gentle peak gave Montavilla its name (sort of), when residents of Mount Tabor Village began referring to the area by the abbreviation used on its streetcar signs: Mt. Ta. Villa.

Akkapong “Earl” Ninsom is beloved in these parts for his bold Thai flavors, but during the pandemic, he and his partners opened Lazy Susan, a charcoal-grill restaurant with dishes that call to mind a cul-de-sac potluck. I order the smoked whitefish spread with fried saltines and French toast with triple-cream Brie, grilled strawberries, and maple-date syrup—the kind of culinary innovations that drive home why Ninsom got a 2022 James Beard nomination for outstanding restaurateur.

Afterward, I stroll around Montavilla’s compact main drag, passing its brewery, wine shop, dive bar, and 1940s cinema. Beckoned by a Technicolor mural of fruits and veggies, I duck into a bakery called Zuckercreme, the kind of ultra-cutesy spot where you half expect to see Strawberry Shortcake and Hello Kitty sharing gossip over a slice of pie. I stock up on some strawberry-lemonade Rice Krispies treats before heading uphill to Mount Tabor Park, which has mellowed considerably since its days as an active volcano. The 636-foot- tall hill makes for excellent views of the skyline across the Willamette River, and I’m charmed by the bufflehead ducks splish-splashing in the reservoir.

Portland is a city of makers, and downtown is a hot spot for some of PDX’s best indie boutiques. I hop a ride across the river to the city’s westside, and at Kiriko Made I browse products made in or inspired by Japan, including the boutique’s own gorgeous textiles: indigo-dyed neckties, tenugui washcloths, denim work shirts, and kimonos. Across the street is a little slice of Mexican craftsmanship at Orox Leather Co., which takes its name from the owners’ current home (Oregon) and family roots (Oaxaca). I’m tempted by a leather-billed “proletariat hat,” which looks like the kind of thing you’d wear to start a labor strike, but instead purchase a set of Oregon-shaped coasters stamped with regional icons like Multnomah Falls.

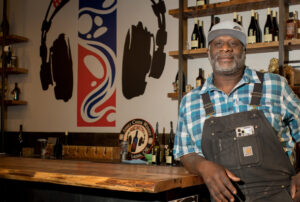

I’m already scheduled to hit up the Willamette Valley and its many wineries this weekend, but I can’t pass The Crick PDX and not walk in. This is the downtown tasting room of Abbey Creek Winery, from the state’s first Black winemaker and vineyard owner, Bertony Faustin. He opened his winery just outside the city in 2008, inspired by his late Haitian father’s “immigrant hustle.” (His Plan B, if things didn’t work out? Make raisins.) Faustin says that for the first five years he didn’t lean into his position as a game-changer: “I didn’t want you to look at me as an inspiration; you would have seen my insecurities.”

These days, though, the vibe inside is as bold and fun-loving as the man himself, with a mural of headphones on the wall and a soundtrack thumping through the bar. “All my wines are hashtagged,” he says. “I think wines should be enjoyed more as a personality or a context than as a varietal.” Faustin introduces me to his pinot noir, #Roundawaygurl, and his malbec, #Blackertheberry. “Maybe she’s just a little extra,” he says slyly. His positivity and playfulness have proven appealing to a wide audience. “I get 60-year-old white folks who love us,” he says. “It’s a reminder that who you are is enough. We don’t have a wine club—we’re a tribe.”

Next, I stroll 15 minutes north through downtown, past the landmark Powell’s City of Books and into the polished industrial-chic Pearl District, for dinner at República, a high-minded new Mexican spot where the succession of courses reads like an encyclopedia of pre-Columbian ingredients, from amaranth to chapulínes (grasshoppers). To start the meal, the waitress brings out a cactus-stuffed memelita (basically a cornmeal canoe) and a tlacoyo (like a thicker stuffed tortilla) with potato, chipotle, and queso fresco. “You’re looking at two of the most ancestral dishes that we know about in the Americas,” she says, noting that they’re topped with cheese and olive oil as a nod to European conquest.

What follows is a centuries-spanning trip through the Mexico of past and present, including hamachi ceviche with mamey salsa; duck breast with a pistachio-enriched mole negro; and an artful dessert of grapefruit zest pavlova with chile cream and charred, candied nopalitos (cactus). Cheeky references to the country’s complex history are sprinkled throughout, including the drink “What Happened in 1519” (aka the year of the Spanish conquest), which is described as a “citrus-forward tequila-based cocktail that is typically consumed at other less-cultured ‘Mexican’ establishments.” Call it a margarita or not, but the tequila has me confident enough to make a bold statement: I think this is the best Mexican restaurant in the United States.

Day 2

A morning kayaking trip, a vegan Vietnamese lunch, and Native America art

Portland’s food scene is ever-expanding, but I have it on good authority that I shouldn’t skip one of its (relatively) old standbys, the 15-year-old Scandinavian spot Broder Café, about a 10-minute ride from my hotel, just off Southeast Division Street’s restaurant row. I order the aebleskiver, Danish pancake balls served with lemon curd and lingonberry jam; lefse, a Norwegian potato crepe; and, because the café boasts the largest collection of aquavit on the West Coast, a Danish Mary breakfast cocktail. I’m sure the Nordic immigrants who came here in the 19th century for the timber and fishing industries didn’t eat this well.

Aquavit means “water of life,” which feels oddly appropriate, given my morning activity: paddling down the Willamette River, which cuts a north-south path through the city. Just south of downtown, I meet my Portland Kayak Company guide, Fred Harsman, a retired math teacher who now spreads the gospel of this underappreciated waterway. He tells me that kayaking boomed during the pandemic, gesturing to his paddle: “These dictate a bit of social distancing!”

As we don our life jackets, I mention that I’m a very novice kayaker. “You can do a totally crappy job and still go forward,” he assures me—and he’s right. We begin paddling out toward the fishhook-shaped Ross Island, a former sand and gravel mine that now functions as a nature reserve, with a particularly robust great blue heron rookery. As Harsman points out bald eagle nests, I ask if the river gets any other wildlife, and he tells me that sea lions have been making their way into these parts, roughly 100 miles from the ocean. “They just hang out by the falls and eat the salmon,” he says. “[Scientists] capture them and take them out to the ocean, and they’re back in a week. They’re American: We love our all-you-can-eat buffets!”

As we round the northern point of the island, its eastern shore gives way to a Mad Max–like post-industrial lagoon, filled with disused dredging machinery and cranes; it’s not a particularly pretty sight, per se, but it is inspiring to see how nature has rushed back in to fill the void since mining ceased in 2001. We continue south, cutting through the “backyards” of houseboats, before making it safely back to shore—sadly, unbothered by sea lions this time around.

I’ve worked up an appetite, and I’m set for lunch at Mama Dút, a vegan Vietnamese deli in the eastside Buckman neighborhood that’s run by the impossibly hip Thuy Pham, who, like many of us, made a complete career 180 during the pandemic: She went from hairstylist to vegan food influencer and activist to James Beard–nominated chef in about two years. Everything on the menu looks incredible, so I ask for a recommendation, and the woman behind the counter says, “We’re one of the few places doing vegan Spam. It’s pretty spot on.” I go for that Spam, on a banh mi topped with musubi sauce, fermented carrots, house kimchi, fried shallots, kimchi aioli, and a tangle of cucumbers, jalapeños, and cilantro. I have to try the “phish” sauce, so I add on a “ryb” bao and toy with the idea of going full vegan— at least until dinner.

A five-minute rideshare trip across the river brings me to the Portland Art Museum, which opened in 1892 and is one of the West Coast’s oldest art museums. It’s filled with the requisite van Goghs and Monets, Cézannes and Renoirs that might have gotten that homesteading generation in a tizzy, but these days, there are no finer works here than what I find tucked up on the second and third floors, in the Northwest and Native American collections. In these dimly lit halls, I feel as though I have the whole place to myself, and I peruse works ranging from a 19th-century Tlingit killer whale hat made with copper and spruce root to the 2019 mixed-media sculpture Green Star Quilt, woven together from circuit boards and brass wire by Yellow Quill First Nation artist Wally Dion.

From here, I amble through downtown, stopping to snap a picture of waterfalls cascading over concrete terraces in Keller Fountain Park before heading back across the river for happy hour at the Little Beast Brewing Beer Garden, which occupies a cozy bungalow on Division Street.

Husband-and-wife founders Charles Porter (an objectively perfect brewer’s name!) and Brenda Crow draw inspiration from the unsung microscopic critters—yeast, various bacteria—that transform raw ingredients into beer. They’re not afraid of funk, either, even naming their barrel-aged beer membership Guardians of Funk. In a town that’s smitten with hop bombs, they churn out a lineup that includes an oak-aged tart red ale, a fruited gose, and a Brett super saison, among the expected IPAs. (This is still Portland, after all.) I sample a crisp Bes tart wheat ale, then walk three whole blocks down the street for dinner.

Chef Thomas Pisha-Duffly opened Oma’s Hideaway last year in honor of his late Indonesian-Chinese grandmother, or oma. The space, however, is anything but matronly; in fact, it might be best described as “Southeast Asian psychedelia,” with coral–and–moray eel wallpaper, a rhinestone-tiled chef’s counter, and a lava lamp. The menu takes an equally kaleidoscopic approach to the flavors of Singaporean and Malaysian hawker stands, serving standouts such as corn fritters with a sweet chili peanut sauce; roti canai, flaky flatbread with parsnip and squash curry; and sour tamarind pork ribs with roasted tomato and jackfruit jeow (a Laotian dipping sauce) and fish sauce caramel. I can’t speak to the authenticity of these dishes, but if this is anything close to an oma’s home cooking, I may need to look into an adult foreign exchange program.

Day 3

Bird-watching, wine tasting, and warehouse dining in the Willamette Valley

A trip to Oregon wouldn’t be complete without a stop in the Willamette Valley, the Napa of the North, which is producing some incredible wines these days. I pick up a rental car, but before I leave town I need to visit one of Portland’s trademark food-cart pods. Many skew scruffy, but Hinterland Bar & Food Carts is a thing of beauty, centered on a cabin-like bar with plentiful open-air seating. At one of the five carts there, Matt’s BBQ Tacos, I order a trio of breakfast tacos on supple, lard-infused flour tortillas: migas (eggs scrambled with tortilla chips), chopped Texas-style brisket, and pork belly with refried beans and queso.

Fully fueled, I hit the road, and as the density of the city gives way to open skies, I gasp—well, actually, I blurt out an expletive—as I catch sight of snowcapped Mount Hood. It’s too early to start wine-tasting, so I kill some time with my favorite folks to hang out with on a new trip: birds. At the 900-plus-acre Tualatin River National Wildlife Refuge, I wander through wetlands and oak savannas, using my dinky point-and-shoot to photograph and identify new species. Within about an hour, I’ve added five new ones to my “life list,” including charismatic California scrub jays, puffball-like bushtits, and cackling geese, which resemble Canada geese who have stubbed their necks.

Finally, I head off to Et Fille Wines (French for “And Daughter”), a storefront tasting room in the small town of Newberg. When this winery opened in 2003, it was about the 150th in the state; now, there are nearly 1,000. Over a glass of rosé, I chat with owner Jessica Mozeico, who was working in biotech in San Francisco when her father, a backyard grape-grower and garage winemaker, called her to talk about opening a winery. He passed away in an accident, but Mozeico has continued his legacy. “My dad and my daughter anchor me,” she says. “As a winery, we are tied to our land, our seasons, and our community, so it’s our job to leave it a better place.” That means sustainable growing practices, chucking the wasteful capsule (the foil sleeve around a wine bottle’s neck), and even opting for lighter bottles to reduce carbon emissions during shipping.

“The thing that makes the Willamette Valley is an intense spirit of collaboration,” Mozeico adds. “Our region produces only 1.5 percent of domestic wines grown in America, but over 20 percent [of those] have Wine Spectator scores over 90. We’re small but mighty.”

For lunch, I make a pit stop in Dundee at Red Hills Market, where I order the platonic ideal of a tuna melt: a baguette with wood-fired Oregon albacore, provolone and Gruyère, lemon zest, capers, and a drizzle of extra-virgin olive oil from Durant Olive Mill, the Pacific Northwest’s only olioteca.

Just five minutes farther on, I reach Remy Wines, which occupies a big yellow farmhouse with a pride flag waving out front. Here, powerhouse winemaker (and interim mayor of McMinnville) Remy Drabkin turns out an award-winning roster of Old World Italian wines. “I’m really focused on making the best wine in the simplest way possible,” she says, pouring me a blueberry-and-black-pepper-spiced dolcetto, made with Piedmont’s most widely grown grape. “It’s about responding to the fruit.”

If Drabkin’s wines are a celebration of tradition, her approach to community-building is anything but. She’s a pioneering voice in the queer winemaking world and a founder of Wine Country Pride, an organization that has distributed pride and Black Lives Matter flags around the valley, donated books with LGBTQ+ characters to public libraries, and even hosted the world’s first queer wine festival this past summer. “We are very focused on inclusion,” she says, “and the wine industry can be very exclusive.”

Drabkin has gotten some pushback from certain sectors of this rural farming region, but she responds defiantly. “I grew up here,” she says. “I’ve lived here almost my whole life. Where do they think I’m gonna go?” It’s no wonder she was elected interim mayor.

I continue along to downtown McMinnville, a buzzing Main Street U.S.A. among the grapevines. I drop my bags off at the Atticus Hotel, where I’m greeted with a glass of local bubbly from R. Stuart & Co. Winery, which has a tasting room right around the corner. This agricultural town has emerged as the hub of wine country, but it was once known as Walnut City—until a 1962 storm blew down entire orchards. The property pays homage to that history with woodworker Jon Basile’s archway of walnuts, a recreation of an art piece that was sent to the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle.

Unsurprisingly for one of the country’s hottest wine regions, the restaurants in the Willamette Valley are almost uniformly excellent. I am surprised, however, to find some of the most innovative cooking I’ve encountered on this trip happening in an old pine-tar shoe-grease factory that now serves as a plant shop, bar, restaurant, and event space. Inside Mac Market, I meet co-owner Diana Riggs, who walks me over to the counter at the café. Chef Kari Kihara came here after working in Michelin-starred kitchens in San Francisco, and she’s now dishing out polished small plates that make the most of the valley’s agricultural spoils. She brings out bright rockfish ceviche with all-local nuoc cham and an appetizer platter to put all others to shame: dill hummus, jalapeño popper dip, charred apple romesco, cara cara marmalade, sunchoke chips, and sourdough naan, made with “Nora,” the sourdough starter. “We love Nora,” Kihara says. “She’s from San Francisco and went to Maine with me before coming here.”

So how did Riggs get into the warehouse-revitalization business? “My husband and I were living in that Airstream over there,” says the former Seattleite, gesturing to a trailer that now serves as a shop selling plants and bulk eco-friendly cleaning products. They’d stop through McMinnville, with their eyeless golden retriever in tow, and one day some dog lovers at the local diner anonymously picked up the check for their breakfast. “We were blown away by it,” she says. “It was just so charming. The first few months, we were like, ‘When is the other shoe gonna drop?’” For Riggs and so many others, it still hasn’t.

As I stroll back to my hotel, I pick up a huckleberry cone from Serendipity Ice Cream, a shop that employs adults living with developmental disabilities. I find it impossible not to feel that sense of charm that wowed Riggs. McMinnville may look quaint, but this isn’t some film-set Mayberry; it’s an industrious town where, much as in Portland, the locals are shaking up the status quo and putting in the work to build a better community, to take something already pretty great and make it even more perfect.

See the City of Roses in Bloom: Fly to this foodie and nature lover’s paradise from more than 200 airports within the United States and an additional 100 international airports.

Next Up: Why You Should Visit Oregon’s Willamette Valley in the Winter