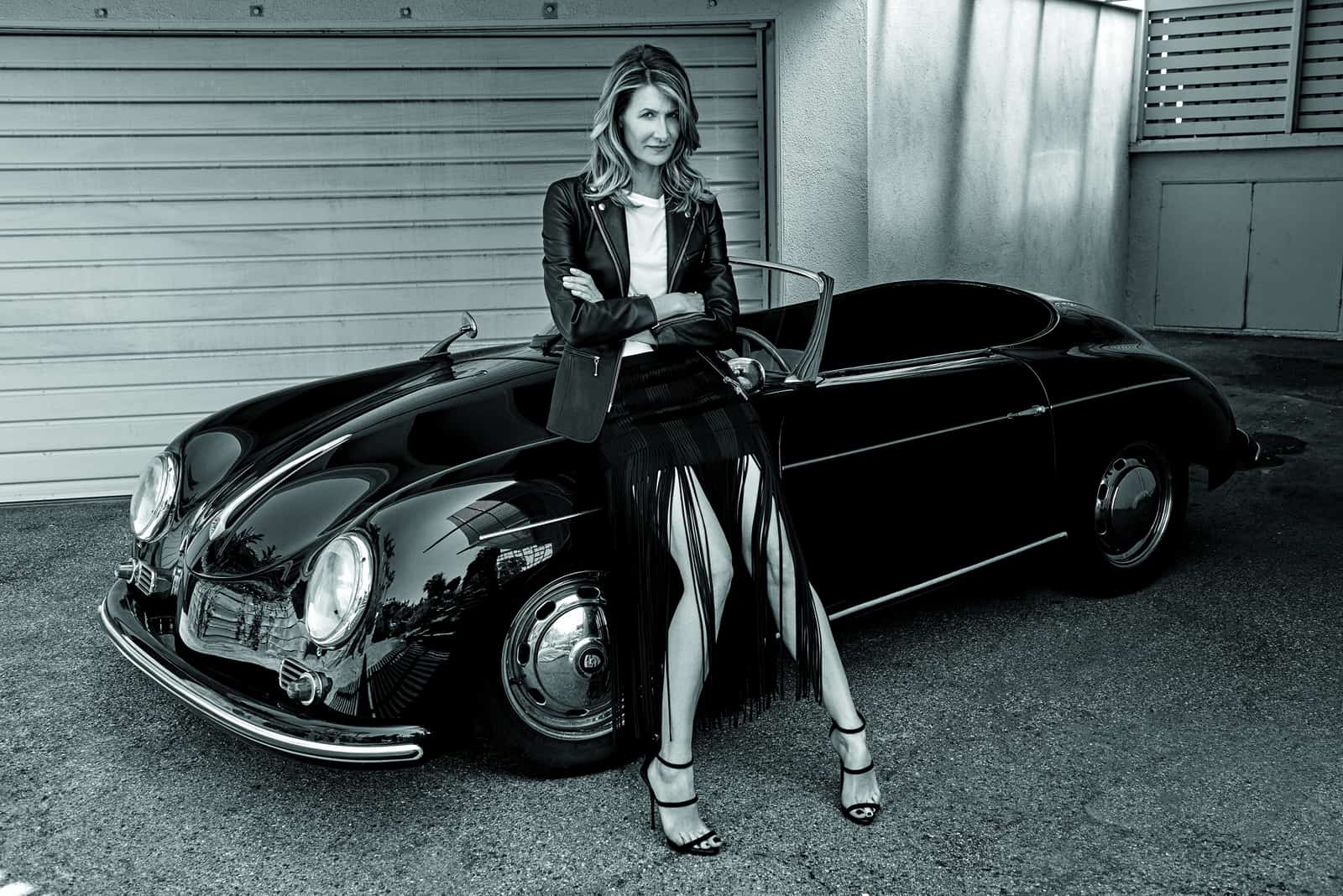

PHOTOGRAPHY BY YU TSAI

Laura Dern is busy. The quintessential second-generation Hollywood actor—the daughter of Bruce Dern and Diane Ladd—has been on a tear over the past two years: picking up an Emmy and a Golden Globe for HBO’s Big Little Lies, leading the Resistance as Vice Admiral Holdo in Star Wars: The Last Jedi, reteaming with David Lynch for the return of Twin Peaks, racking up quirky features (The Founder, Wilson), making a cameo as a miniature sales rep in Alexander Payne’s Downsizing, and setting her sights firmly on changing the imbalanced power structures of the town and industry she loves. This almost frenzied creative pace has led some pop culture writers to declare a “Dernaissance.” While pithy, the term isn’t quite right: In the 45 years since her first uncredited on-screen appearance, at age 6 in her mother’s film White Lightning, Dern has amassed one of the most consistently interesting bodies of work in Hollywood.

And she’s showing no signs of slowing down. In the pipeline are a second season of Big Little Lies (made even “bigger” by the addition of Meryl Streep), a new Noah Baumbach film, and JT LeRoy, in which she’ll star as struggling writer Laura Albert, who infamously created a male literary persona that hoodwinked the publishing industry. Plus, this month, HBO debuts her latest film, The Tale, which opened to rapturous praise at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. It’s an eerily prescient film for the #MeToo moment. Dern stars as a loosely fictionalized version of documentary filmmaker Jennifer Fox, who must come to terms with the fact that she was abused at age 13 by her beloved track coach and horse-riding instructor—a relationship she had convinced herself for decades was consensual and romantic. It’s a twisty drama that plays with truth and lies and the stories we tell ourselves to get by.

Despite this nonstop schedule—today alone she will record audio for an upcoming film, attend a meeting with the Academy, and join in a Q&A about the Time’s Up movement—Dern exudes a breezy California vibe over lunch at a Beverly Hills restaurant. Imposingly tall, she’s dressed in salmon pants and a beaded black blazer and sports blackout sunglasses that she takes on and off throughout the meal. She hugs hello and is quick to show off her spot-on David Lynch impersonation. She’s proud of her iPhone wallpaper (a pug dressed as Twin Peaks’s Diane for Halloween) and is the kind of person who calls her asparagus and beet salad “miraculous” and means it. But she can also be deadly serious: about #MeToo, Time’s Up, and gun control, an issue in support of which she marched through the streets of LA three days earlier. It’s not hard to see why Star Wars chose her to lead the Resistance.

From the outside, the past year seems to have been monumental for you. Did it feel as major from the inside?

Without doubt. One of the things that I think is so delicious is that it feels cumulative. To me, it’s about coming into my own. When I was younger, if there was a moment where I was particularly busy, the term was, “She’s hot.”

Did you feel like that phrasing diminished it somehow?

It’s unfortunate that it does imply the temporary nature of the actor’s career. But it also does not seem strategic or planned. And in a way, this is strategic and planned. I want to be ferocious in my choices more than ever, and I want to do everything. And I’m saying yes.

When did the ball get rolling on this particular chapter?

The beginning of my career. When I was in my early 20s, Martin Scorsese and I had a beautiful conversation about my career. I was an extra in the movie he did with my mother, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. He said something that meant so much to me: “I’m watching your choices, and you’re making choices as an actor as if you were a filmmaker, where you’re building a body of work. I hope you keep doing that.”

Why do you think he saw you that way?

What he saw was that I was choosing [projects] based on brave filmmakers. It was definitely the Brat Pack generation, big TV series, the beginning of franchise action films, teen comedies. So there were a lot of different journeys to success. Because I had parents who thrived at working with interesting filmmakers, I was raised to understand that if you get five scenes in a Peter Bogdanovich film or a cameo with Robert Altman, you don’t do the lead in the teen movie. You learn from great directors, and you challenge yourself with complicated characters. That’s why I fell in love with acting.

This past year alone has seen you play a diverse array of roles. Are the characters you’re drawn to linked in some way?

I think worth, value, is maybe one of the biggest through lines. Whether it’s someone who doesn’t know their own worth or, frankly, doesn’t even know they’re entitled to feeling that they have a place at the table or a voice in the world. That really interests me. Renata in Big Little Lies—who is the wealthiest, most ambitious, powerful, only woman who has a seat at the table in Silicon Valley—doesn’t feel like she’s allowed to have friends, doesn’t feel liked or seen among women. Or Citizen Ruth, who doesn’t even know anybody could give a s*** if she spoke out and doesn’t have self respect. That really interests me deeply.

You’re never afraid to tackle characters who might not seem sympathetic at first, like the whistle blower Amy Jellicoe in HBO’s Enlightened. It ended up being my favorite television show of all time, but for the first few episodes, I was thinking—

“Eww”? That was our goal! Which is a weird goal. But the goal was to make her impossible. Impossible to love for her ex-husband, for her own mother, for her mom’s dog—let alone in the workplace. And yet, maybe that impossible person is impossible because their anger could change a generation. Maybe she’s the only one who would get in the face of a Monsanto and say, “Enough!” You know, people who want to be likable and palatable don’t always start revolutions.

She was defined by this righteous rage.

And everywhere I go now, I feel like I’m sitting with Amy Jellicoe. The whole country is Amy Jellicoe. It’s amazing. Righteous rage, which we tried to look at in the show, is what’s waking up the masses and maybe even Congress now. It’s amazing that that is what’s effecting change in a way that’s never happened before.

There’s something really powerful about a female character who is allowed to be unpalatable and complicated.

I love that people are so who they are that they forget they are supposed to behave in a certain way—whether to respect others or even to have any self-respect. But if I can’t empathize with the person, I can’t play the part.

So how do you find a way in?

Storytellers have a goal in mind. For me, it’s about empathy. You don’t have to love the people I play, but I hope you’ll understand what desperation and fear and shame do to people. Because if we’re learning where we judge the most, then maybe we’re going to crack open to ourselves and to each other. I think that’s why Big Little Lies is so interesting for us. To have people repelled after the first episode and say, “Ugh, rich-white-women problems?” And those same people almost feel embarrassed several episodes in that they were feeling that way about women going through so much was a really fun thing.

Anecdotally, I had a few male friends who had a similar reaction and then came around to being the show’s biggest cheerleaders.

And how beautiful that men are shifting in the same way that women are shifting! We’re having this amazing paradigm shift where we’re seeing characters as characters. We’re not going to Black Panther because it’s a “diverse” action film franchise. And we’re not seeing Big Little Lies going, “OK, chick flick, I guess I’ll see it because my girlfriend likes it.”

It seems like that way of thinking is relatively new.

I mean, we really are a third-world country. You know, half of French filmmakers are women. Heads of state across the globe have been women—have been people of color—for many, many years.

What do you think accounts for that? Especially in your industry?

I don’t know. We act like a very young country. The last few years, we’re thinking the same way we were when we were shaping this country or burning witches. It’s such puritanical thinking. I’ve been privileged to mostly live a life where I wasn’t realizing how insidious it was—until recently. I wasn’t understanding the wealth of creativity and genius in women around me. I was in a sexist mind-set. I mean, how could I not have been when I was on movie sets starting at 11 and men were doing my hair and makeup? Men were doing every single job on that set. I have been on movies where I was the only female, including the cast and crew—maybe a costume assistant. That’s pretty radical, and I wasn’t going, “What’s going on? This is insane.”

Is it something you’re actively looking to change on the sets you’re working on now?

Male and female actors, cinematographers, directors, writers, producers are all taking a very long, hard look at themselves and their choices. If our mind-set is an older white man walks in the room and you assume he knows more or has become more educated because he had more chances and more privilege, then you have to have a paradigm shift. How many times have you heard, “I don’t know if she can handle it: It’s a big movie. It’s an effects movie. A small indie? OK.” What, do we have to have more muscle power to lift the sets ourselves?

Legacy is deeply important to me and my family, but it’s not as important as progress

Your latest film, The Tale, feels so timely in the era of #MeToo and the gymnastics abuse scandal. How do you approach such a delicate subject?

I think what moves me the most about Jennifer’s bravery in her storytelling was how she survived the experience by imagining it to be a love story so that she wasn’t a victim. She knew she would crush herself and her potential as a woman and her art and her fire as a documentarian. All those parts of her she felt would have been stymied if she lived a life of a victim. So she told herself a story. It was boy meets girl, falls in love. Yes, he’s older, but it’s the ’70s. And many of us have had a horrible experience. I mean, the hazy experiences of males and females in college, where it’s like, “It wasn’t that bad.” You try to justify. You replay things that haunt you.

There’s been a lot of talk this year about the ways truth can be manipulated. Did this project impact the way you think about truth and lies?

I think so. The part that really moves me is that it’s not just about truth being good guys and lies being bad guys. When someone is in their own misguided self, but they have nobleness, we have to be a part of that journey. How are we helping each other? What is restorative justice, culturally?

You called for restorative justice during your Golden Globe acceptance speech. What does that term mean to you?

I think there’s something extraordinary about holding up brave people who are accountable and, instead of banishing them, rewarding them. Let’s take our industry for an example. A studio has someone on a set who has sexually assaulted one or more people. The truth is, that individual, in this culture, could take down a studio if it’s protected or covered up. So if a young [director] trainee is lucky to have this gig with a very important director and witnesses this person, who is perhaps their boss, they have been raised to believe in our culture that they will lose everything and be blacklisted [if they report the crimes]. But if they go to the powers that be anyway and say what they’ve witnessed to protect others, that person deserves us to rally around them. The studio should give that person a raise and more work. The paradigm shift of rewarding risk is how I want to raise my children to behave. And we’re not there yet.

Is there a way for this to take hold industry-wide?

Anywhere I’m involved, I demand to be involved with organizations that are moving forward. As long as others are meeting me in the longing to follow this paradigm shift in gender and diversity parity, in membership, in the kinds of films that are supported and honored… Legacy is deeply important to me and my family, but it’s not as important as progress.

With everything that’s happening, how do you stay so grounded?

Well, my daughter is so passionate and ferocious, and she spoke [at the March for Our Lives]. We look for the voice of the generation in the zeitgeist. When we’re waiting again for the white, Harvard-grad boy to effect policy change, and that person is Emma González, we’ve shattered the belief system that it has to look a certain way. So that’s what makes me most excited.

You’re hopeful?

I’m hopeful because it doesn’t look like it’s ever looked before. The films don’t feel like they ever have before. The generation that thought it was going to protect a certain story is now going to lose everything if they don’t change. The boardrooms, the unions, the heads of business, admissions at schools, they need gender and diversity parity. They need to grant the new generation voices that aren’t based on wealth or opportunity. And in terms of work, I feel like there are more people having more opportunities to be storytellers, which means more great films. As an actor, that’s so inspiring.

One of the things that was refreshing about Big Little Lies is the way the media was giddy over this behind-the-scenes creative sisterhood. Where did that camaraderie begin?

For me personally, all roads lead back to Cheryl Strayed [Dern and Reese Witherspoon costarred in the 2014 adaptation of Strayed’s Wild]. Who knew that Cheryl walking the PCT [Pacific Crest Trail] and learning how to heal grief would be the thing that brought me, Reese, [director] Jean-Marc Vallée, and [producer] Bruna Papandrea together? That was its own love story. From that, there was a deep connection and family and sisterhood. It was really beautiful.

So you had to come back for a second season.

I had to. And then Meryl Streep—who is texting me right now. “I’m kind of busy; Meryl’s texting me.” [Laughs.]

You’ve been in this industry for decades. Can you possibly still feel starstruck?

I did. And then time wasn’t on my side; there’s no time to be starstruck. We had work to do. We wanted to work together on effecting change in certain areas of activism. But then every text, I’m like, “Hello, amazing goddess guru Meryl.” At what point do I drop those things?!