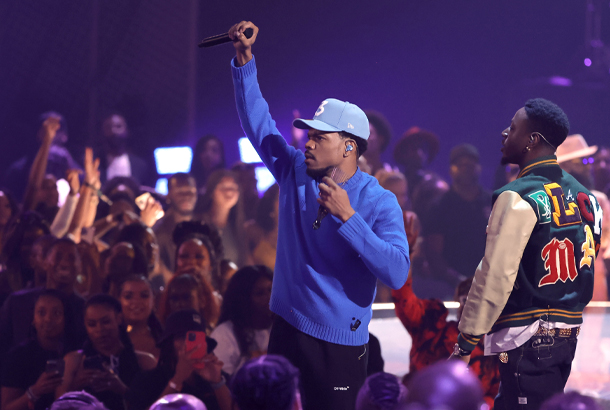

The Chicago rapper illuminates Black art with a new album and the upcoming Black Star Line Festival in Ghana

In early 2022, Chicago-bred Chance the Rapper took a trip to Ghana with fellow rapper Vic Mensa and poet Aja Monet. As they ran out into the water at Accra’s Laboma Beach on the last night of their stay, Chance (born Chancelor Johnathan Bennett) had an epiphany. “I feel like I’ve played every nook and cranny, but I’ve only played one show ever on the continent,” he told his friends. “We should do a show at this beach and create something sustainable.” By the time they stepped off the sand that evening, the Black Star Line Festival, Chance and Mensa’s upcoming music and art fest, was on its way to becoming a reality.

The name of the festival and the title of Chance’s upcoming album, Star Line Gallery, were inspired by a shipping company conceived in 1919 by civil rights leader Marcus Garvey, who aimed to create an economic network between Africa and Black people in the Americas. Similarly, Chance is looking to cultivate Black connectedness with the festival, which aims to be a bridge between Black people and artists of the African Diaspora. “Expect amazing music, street art, fine artists, food vendors, and clothing designers,” he says. “It’s been like a fun house coming up with ways to express our Blackness.”

A UNICEF Chicago Humanitarian Award recipient and Grammy Award-winning independent artist, Chance began championing the empowerment of Black people, and creating lanes to do so, even before he dropped his first mixtape in 2012. For his new record, he called on Black artists from across the globe to make interdisciplinary works for the cover art of each song. Chance spoke with Hemispheres from West Africa, where he’s gearing up for the Black Star Line Festival, which kicks off in Accra on January 6.

You took your first trip to Ghana earlier this year. What was that like?

It was kind of like going to outer space or something. It’s something you hear about your whole life, and you feel deeply connected to, but you haven’t really experienced it. So, just being a Black American, it was a big deal. I was blown away in terms of the friendships I made, and the art scene, which really inspired my new project. The most impactful thing I learned about was Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana. I went to a museum built in his honor, and I learned about how integral Ghana was to furthering the liberation of Black folks. I found out how inspired he was by Marcus Garvey, and how so much of the framework of the nation is built on Pan-Africanism and global Blackness, and it just made me want to learn more.

How did that experience change you?

It made me understand myself better in terms of my place in the world—that I’m a part of a large, or the biggest, network of people—and I think I started to understand contextually where my music belongs in terms of who I should be making it for, the type of spirit or engagement that I should have with it. And it really made me more comfortable in my skin, just understanding who I am, who I am to people globally, and what it is that I can do when I work in tandem with others. A lot of things are naturally poetic about [Ghana]: That makes you learn to look inward, to know yourself, and to celebrate yourself.

How much research into your roots had you done before this initial trip to Ghana?

So, really, none. I’ve never done a DNA test. I don’t believe in DNA tests. But I had texted in a group chat with my family, “Hey, I’m visiting Ghana tomorrow. Is there anybody that you can hook me up with?” I found out literally the day that I was about to board the plane that all of my family actually had been traveling to Ghana since the early ’70s or late ’60s because my great-great-grandfather was a Garveyist [a Black nationalist who follows the policies espoused by Marcus Garvey], and my great-grandmother was involved in building churches and schools here. Walking in a place where my grandmother stood, where my cousin stood, really gave me the confidence to feel like I’m not walking in a foreign place. This is home.

That’s incredible. Have you taken your two daughters, who are 7 and 3, to West Africa yet?

I have not. I think I’m going to bring them in January when we do the show—and I’ll bring a nanny. I’ve been kind of working around the clock while I’ve been out here, but I brought them back a drum, this gold elephant, and a gold lion. They get excited when I get back, because they’re always like, What did you bring us?

Did you share with them the impact your visits have had on you?

I taught them that Africa’s the birthplace of civilization. This is where everybody comes from in some shape, form, or fashion. I taught them that when I go there, we all look the same, that there’s a massive amount of love there, and that they’re going to come one day. But they’re still kids. They still think of it as, like, Dad’s going to work.

This summer, you organized a trip to Ghana for a group of teens from Chicago. How did that come about, and what was it like to be able to give that experience to the next generation?

It was incredible. I had just came to Ghana for the first time a few months before, and to be bringing other people, younger people, on the second trip out there and showing them around is a testament to how well I was hosted the first time I came—because at that point, I could get them in touch with people that were in the same fields as these kids. What was deep about it is I’ve kind of been doing this my whole life. A lot of my friends that are artists now, we all grew up in this open-mic after-school program together, and when our mentor passed away a lot of us were early in our careers. Myself, Vic Mensa, Noname, and a few others came together and started our own open mic. There’s a lot of situations where my group of friends out of Chicago had to, upon learning something, immediately interpret and redisperse that information to a younger audience. We’re getting better at it, I guess.

Ghanaian artists Sarkodie and King Promise will perform at your inaugural Black Star Line Festival. What else can we expect, and where did you draw inspiration from for the festival?

It’s a callback to the Pan-African Festival of Algiers in 1969, which was a conference of Black thought leaders, writers, and activists. And it’s a callback to Zaire, when Muhammad Ali and George Foreman fought, and James Brown put together a concert. It’s a callback to the Million Man March. It’s just a demonstration of thousands of Black bodies in peace, dancing, singing, cooking, having fun.

Who do you hope attends?

Black people.

Right. Well, yes, we’ll be there in droves. But are you trying to get a big U.S. audience to come out?

The way that I think about it is, we’re all Black, regardless of citizenship, status, or anything. I do hope that a lot of Black Americans come. I hope that a lot of Black Islanders come. I hope a lot of Black folks from the U.K. come. I hope a lot of Black Australians come. I hope a lot of Black Asians come. We’re hoping for people from all across the continent to fly in. The goal is to bring Black folks together, period. It’s basically a convention of Black folks demonstrating their connectedness in one singular space. But the word I keep using, the word that I learned in social studies in sixth grade, is cultural diffusion: This is a big opportunity for us to all get around sharing conversation in confidence and grow with each other.

You collaborated with a lot of visual artists on your latest album, including Chicago-based painter Nikko Washington and Gabonese photographer Yannis Davy Guibinga. How did your creative process evolve on Star Line Gallery?

My music has always been based off taking a single idea and attacking it from different angles. When I came to Ghana, I recognized the power of our visual art as Black people. I got inspired by artists like Amoako Boafo, Otis [Kwame Kye] Quaicoe, and Naïla Opiangah, who did [artwork for] my first single, “Child of God.” Instead of just going to a rapper and saying, “OK, this is what I’m rapping about, would you add a verse?”, or a singer, asking if they would add a chorus, it’s going to a visual artist and saying, “What does this make you think of? How does this make you feel?” Their words end up becoming my words, and my words end up becoming their painting. All of these conversations I’m having in the music this time are much more fleshed out. It’s been a great experience.

Over the years you’ve remained an indie artist, owning your own work and creativity. Why is Black ownership and artistic ownership so key?

I think autonomy is the key to human existence—like, being able to make your own decisions and feel the freedom of just being yourself. I’m finding that I’ve grown to inspire a new generation of more and more independent Black artists. I think we’re at a point where Black folks are recognizing their own power and the stakes that we hold in all industries. In order for me to make what I make, I have to be in this position, and in order for new artists to continue to believe that it’s possible, I have to remain in this space and be as successful as possible.

How does that independence affect your art?

It’s given me time. I don’t ever have deadlines, have to turn an album in, or be put in a position where I can’t do a performance because my label doesn’t want to license my music. I’m in a lot of positions where what I make is able to condemn lifestyles, brands, corporations, or whoever the f *** I don’t f *** with, and that’s the freedom that everybody doesn’t necessarily have unless they end up with that sort of leverage. And so I think it’s not something that’s easy, but it’s something that’s right, and that makes it a little bit easier.