If you draw a squiggly bean shape about the size of South Carolina, starting north of San Antonio, moving up and west to Fredericksburg, then heading east toward Austin, you’ll have Texas Hill Country. A place that is as much a state of mind as it is a place on a map.

Underneath the rolling limestone hills, some grassy, some forested in oaks, junipers, and wildflowers, are caves and aquifers feeding a web of springs, rivers, and falls. The subterranean activity is a metaphor, or maybe even a reason, for what’s happening aboveground. Hill Country is laid-back, but there’s also a bubbling energy, a vitality shared by ranchers, vintners, pitmasters, and big-city transplants searching for a new—and old—way of life. It’s a place where the bucolic and the urbane blend, and the lines are deliciously blurred.

Day 1

Competing barbecue families in Lockhart and a picker circle in Luckenbach

All road trips should start with barbecue.

When in Hill Country, that means sampling the smoked meats of Lockhart, the “Barbecue Capital of Texas,” about 30 minutes south of Austin. That slogan isn’t a boast; it’s officially decreed by the Texas Legislature.

Barbecue has been at the center of Lockhart life since the early 1800s, when the city’s founders arrived with cattle and no refrigeration, and later when the town became a key stop on the Chisholm Trail, the route cowboys used to drive their herds to the railroads in Kansas.

These days, another kind of migration is passing through: priced-out city folk.

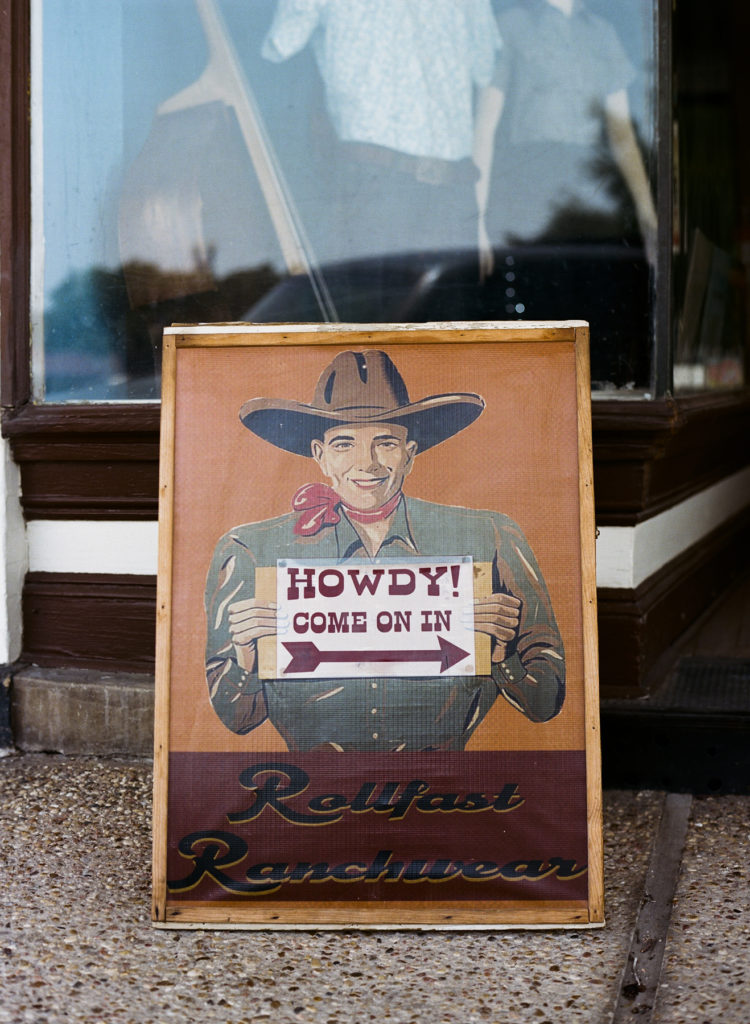

Since it’s a bit early for smoked meats, I walk through the historic town square. Signs of newcomers seeking cheaper rents and a rural idyll abound: Frilly post-frontier Victorian facades look freshly painted and bear signs for craft cocktails, handtossed pizzas, and kombucha on tap.

I take the bougie bait and have a glass—a fermented elixir to prepare me for the culinary carnage to come—at Take Care Apothecary, which sells staples like sage smudges, soy candles, and CBD gummies. When the shopkeep tells me she just landed here from Brooklyn, it takes only about three seconds for my brain to form images of packing up all my stuff and doing the same.

I wander on, past a clock museum and the exuberant man sard-style Caldwell County Courthouse (a film location go-to featured in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, Waiting for Guffman, and The Leftovers), peeking into antiques stores hawking Mid-Century Modern hutches and Gene Autry movie posters. This is all a prelude, however, to Kreuz Market, as it’s time to get my first taste of Lockhart’s claim to fame.

The Kreuz story starts in Germany, where the family smoked meat and made sausage, traditions they brought with them to Central Texas. They bought the market in 1900, and in 1948 they sold it to their butcher, Edgar Schmidt, who in turn passed it on to his kids. Sadly, a family feud ensued, culminating in Schmidt’s sons, who owned the Kreuz name, building a new location (the current one) and their sister renaming the original spot Smitty’s Market in 1999. A photo on the wall captures the drama: pitmaster Roy Perez and Lehman Schmidt dragging a metal tub full of hot coals down the street from the old pit to the new ones.

The folks at Kreuz Market knows who they are, though, and the no-nonsense approach is summed up by a sign inside that reads, “Our traditions since 1900: No Barbecue Sauce (nothing to hide) No Forks (they are at the end of your arm) No Kidding (see owner’s face).” When I approach the counter in front of the open fire pits, a guy looks up at me and says, “You don’t know what you want,” calling my bluff as if we were standing there with cards playing poker. I punt, unheroically. “I’m here for your most famous thing.” He grabs the dry-rubbed brisket, asking me if I’m OK with the slices not having a lot of fat. I look down and see marbled slices, fat wide as an ax handle, and respond, coolly, “Sure.”

I take my bundle of beef and butcher paper into the barnlike dining hall, where the customers are getting down to brass tacks: no music, no jawing, no-frills. I dig in with my God-given forks, reveling especially in the chewy crust, and leave not a crumb for the kettle of black vultures circling overhead.

Round two is a few blocks away, at Black’s Barbecue. Upon arriving, I stop to admire the “giant beef ribs!” sign, and an older gentleman on the porch offers to take a photo of me with it. So, that exists. Inside, another sign brags that this is “the oldest and best BBQ restaurant continuously owned by the same family.” As at Kreuz, Black’s long road to today is mapped out on the walls. Edgar Black Sr. opened it in 1932, and by 1965 he was shaking the hand of fellow Hill Country boy Lyndon B. Johnson.

I head to the counter to order, and, as if on cue, Hank Williams starts to pour from the speakers: “Now I ain’t had a kiss since I fell out of my crib/It looks to me like I’ve been cheated out of my rib.” I order a jalapeño corn muffin and a pickle and one rib. Second-guessing myself, I impulsively ask for a pork rib too. When I pick up the tray, I think of The Flintstones, and Fred’s order of brontosaurus ribs tipping his car over at the drive-in.

In the cozy, wood-paneled dining room, jaunty Santa hats try to cheer up the taxidermy bucks’ heads mounted on the wall. I wonder what their glass eyes have seen. Were they here when Edgar Jr. and his wife, Norma Jean, were the first in these environs to desegregate, creating a local stir? Barrett Black told Edible Austin that when people asked his grandparents, “Where are the [Black people] going to sit? ” they answered, “Wherever the hell they want.” I douse my ribs with sauce made from Norma Jean’s recipe; the feisty, tangy taste surely fit her nature.

Doggie bag in hand, I get back in the car and drive northwest. Just past LBJ’s hometown, Johnson City, the highway runs through hills alongside the Pedernales River. The fluffy white tails of speckled fawns scatter like popping popcorn in my high beams. Down a small road, between South Grape Creek and Snail Creek, is Luckenbach, an unincorporated 172-year-old settlement with a trading post/ post office that’s nearly as old and a population you don’t need one whole hand to count.

Founded by a German preacher, the post did well handling trade between farmers and the Comanche tribe. In 1970, descendants of the preacher sold to the larger-than-life writer/rancher/philosopher Hondo Crouch, who hosted cheeky happenings like hug-ins and wasp season celebrations. In 1972, Willie Nelson was among the 20,000 people who showed up for the First Annual Luckenbach World’s Fair; in 1977, Waylon Jennings released the crossover hit “Luckenbach Texas (Back to the Basics of Love),” cementing the place’s fame.

I sidle up to the old trading post’s bar—it’s covered in memorabilia from its groovy days, but also further back, when it was the only post office for many miles—and drink a local Altstadt beer. The tiniest stage is shoehorned in the corner, and two men who look like cowboys with guitars are in between songs. In front of them, strangers on a little bench trade stories about RV life. “We just travel,” says one. “Idaho. Europe. We’re free.” A lady with a golden retriever calls for Merle Haggard’s tearjerker “Silver Wings,” and the boys oblige, singing harmonies sweeter than stolen honey.

At the song’s end, I tear myself away and drive to my charming inn, the Fredericksburg Herb Farm. As I find my way through the garden, two well-fed cats circle me, meowing and pawing at my doggie bag. I apologize to them, close my door, and dig in for a midnight snack.

Day 2

A giant pink Enchanted Rock, wine tasting, and the Cowboy Capital of the World

In a town named after Prince Frederick of Prussia, you’re never far from a souvenir with German roots. There are the “Willkommen” signs, the Marktplatz, where a maypole traces the settlers’ story in folk art figurines, and the fancy frontier storefronts begging to be remade in gingerbread. There’s nothing German about my breakfasteggs Benedict with housecured salmon and asparagus at Caliche Coffee Bar & Roastery—but I like how the café takes its name from a type of white sedimentary rock that’s common in these parts.

After all, I’m headed north to see Enchanted Rock State Natural Area and its massive, billion-year-old mound of pink granite.

About five miles down the road, the rock comes into view, playing peekaboo between dew-frosted hills and rusty old tractors. At the park gate, the ranger tells me I’m lucky I made it in today. Starting this afternoon, they’re closing for a few days for a public deer hunt; feral hogs weighing up to 400 pounds and “causing all kinds of destruction” will be fair game too.

I’m grateful I made the cutoff but disappointed I can’t return tonight to stargaze, as this is an International Dark Sky Park, with night skies dark enough that visitors can see the Milky Way. As a consolation, the sky is putting on a show for me now. Cloudless and the color of dark denim, it’s crowning the pink dome as I begin the 425-foot climb.

There’s a holiness in the stillness up here. Enchanted Rock is a sacred place for Native people. Some believe it’s haunted and that the cracking sounds it emits—which boring men of science ascribe to the granite expanding and contracting as temperatures vacillate—are perturbed spirits cackling. When I come upon a vernal pool the size of a puddle, I crouch down and see a bird’s buffet of tiny insects and minuscule fairy shrimp swimming upside down, dining on algae.

I descend and get back on the road, heading southeast to William Chris Vineyards. Heath Tolleson, a tasting room ambassador, pours me a glass of petit verdot before leading me through the vineyards and into the shade of a 400-year old oak to share some history. After meeting in 2006, William Blackmon and Chris Brundrett decided to employ Old World winemaking processes using 100 percent Texas-grown grapes—a radical idea at the time. “Texas wine wouldn’t be as far as it is if it weren’t for Bill,” Tolleson says, “And Chris, he’s the avantgarde. Last year, he was on Wine Enthusiast’s ‘40 Under 40,’ a first for Texas wine.” Another Texas first came when two of their wines won gold and silver at the Concours International de Lyon in 2014. One can only imagine the French judges being aghast when their origin was revealed.

I wish I had another day and a driver—so I could do a proper wine country tour. There are nearly 80 wineries in the region, including Singing Water Vineyards, which, like William Chris, grows all its own grapes, offering festive blends such as a cab-merlot Texas Reserve, and the storied Fall Creek Vineyards, whose owners earned the region its appellation in 1990.

Instead, I’m allowing my growling stomach to guide me to Otto’s German Bistro, a farm-to-table restaurant off Fredericksburg’s Main Street. On the front porch, with a nice breeze blowing, I try the Bavarian frittatensuppe (beef broth with rainbow carrots and celery) and duck schnitzel with käsespätzle, cranberry marmalade, and pickled peppers.

On my way south, I take a detour to see Stonehenge II (which is on my list of Hill Country hyperboles, next to the world’s largest pecan and the world’s largest cowboy boots). Just off the highway, and without a lot of explanation, it’s somewhere between the ancient original and Spinal Tap’s stage prop; as with its prehistoric muse, its purpose is unknown, and perhaps unknowable. I lie on the lawn that slopes to the banks of the Guadalupe River, watching ducks glide by, wondering if they speak Druid.

Thirty miles more, and I’m in Bandera, a two-fisted, rootin’ tootin’ town that has turned its homegrown cowboys into cash cows. As the reigning Cowboy Capital of the World™, Bandera has more boots and saucer-size belt buckles than you can shake a stick at, and hats so big that when a pickup truck passes by, you’d swear the hats are actually driving.

I pull up to Dixie Dude Ranch just as the sun is starting to set and spot owner Clay Conoly out on the porch. He’s got on the requisite cowboy boots and hat, to go with a thick gray mustache, warm eyes, and a steady, comforting drawl.

Dixie’s been in his family since 1901, passed down from generation to generation since his great-grandparents. He tells me they’ve been having a long dry spell in the area. “So dry, armadillos and foxes, normally nocturnal, are looking for water during the day.” He introduces me to Pancho, a bandanna-wearing golden retriever, then hops in a truck and waves goodbye. I scoot inside the mess hall for a plate of grilled pork and vegetables and get to chatting with Patricia Moore, who’s been talking up Bandera in a professional capacity for over 30 years.

Full as ticks, we walk out to the campfire. “Younger folk might think a place like this is as boring a place as God ever made,” Moore says, poking a marshmallow with a stick. “It doesn’t have the frenetic aspects to it. But once they’re here, they fall in love. This is not a place of have-to’s, it’s a place of do whatever your do is.” From the darkness beyond the fire, a meowing black cat appears, seeking kudos for having caught the mouse in her mouth. Sufficiently feted, she sits by our feet and chows down. Three more cats line up behind her, like airplanes waiting for takeoff. Doing their do.

Looking up at the sky, I’m no longer sore over not getting back to Enchanted Rock. There’s nothing out here to obscure the brilliance of the stars. The Seven Sisters of the Pleiades are easy to spot. Jupiter and Saturn are so clear, nearly on top of each other an alignment, by the way, that hasn’t been so closely observable since 1226—and Sirius is pulsing red, then white, then blue, on repeat like a message from out there. What could be more Texas, I think, than a lone star blinking the colors of Old Glory?

Day 3

Horseback riding with Bubba, dinosaur tracks, and historic Gruene

I wake early and watch the embers fade in the fire I made before going to bed. My sheets smell of delicious smoked oak. After a quick eggs-and bacon breakfast, I head out to find Bubba, the ranch’s wrangler. Thin as a lasso in chaps, with a fluffy white handlebar mustache that’s more egret-in-flight than horseshoe, Bubba is flaunting his cowboy swagger by the corral. My mind’s scrambled with inherited notions about Texas, and something falls out of it to make Bubba chuckle and say, “People come and think we’re wearin’ six guns and all that stuff.” I acknowledge that I’m those people.

Bubba mounts a horse named Buckshot. I climb atop one named Blue, and we set off yonder into the hills. Blue’s ears are back, and I ask if that means he’s ornery. “Probably,” says Bubba. “Blue’s an alpha,” which for no reason thrills me. The trail winds through the hills above the ranch, over chunks of white caliche rock. It’s steep in parts, and when it gets narrow, Blue gets close to the bushy cedars, so their bristly branches give his shiny brown sides a good scratch.

At the top, we take in the view of the ranch, with the big old barn that’s been there for more than 100 years, and the uninterrupted rolling hills beyond. Bubba points to a thirsty armadillo shuffling in the dirt. “They’re kinda kule,” he says. On the way back down, he tells me that Bandera was a staging area for the Western Cattle Trail in the 1870s. “Cowboys would be driving cattle, and Bandera was a place they could stop and have some fun and get into some trouble.” He used to compete at rodeos, “buckin’ horses and bulls, anything I could find to ride,” but he’s settled down now, newly married to a woman who came here from Holland as a guest and returned to be his bride. “I wasn’t lookin’ for a girlfriend—I had three already. But I couldn’t be happier. It’s like a Hallmark movie.”

Back at the ranch—amid a melee of goats, donkeys, pigs, wild boars, dogs, cats, and noble peacocks—I bid a heavy-hearted farewell to Bubba and hit the road. I make for Bandera, crossing the Medina River just as two kids jump in for a swim, and stop at Gringo’s Burritos for a quick bite before heading east to Government Canyon State Natural Area, where I’m fixing to see dinosaur tracks.

Park ranger John Koepke guides me through the woods to the footprints, marveling at the perfect storm of conditions that a l lowed them to endure. “Remember, 110 million years ago, the seas were rising, and this part of Texas was a shoreline,” he says. “But it wasn’t a nice, white sandy beach; it was a slurry of limy mud. Imagine a dog scampering over new sidewalk before it’s hardened, making tracks. But here’s the kicker: The slurry had to stay dry enough, long enough, for it to become rock.”

All ginned up to time-travel, we crouch down to inspect two sets of prints—stomped into the ground by two species, thousands of years apart. The older ones were left by an Acrocanthosaurus, a two-legged carnivore similar to Tyrannosaurus rex.

Gaping holes, some two feet long, show three huge toes crowned by flesh-tearing claws. The newer set was made by a juvenile Sauroposeidon (“lizard earthquake god”) who moseyed about on four legs and ate plants. These marks are round and seem more delicate somehow, even though, at 55 feet, this beast would have towered over the Acrocanthosaurus. We leave the tracks and trek up the bluff to get a pterodactyl’s-eye view of them.

Back on the highway, I drive south until I reach historic Gruene. Gruene is the kind of absurdly cute village that belongs inside a snow globe. Set on a gentle ridge above the Guadalupe River, the town was built in the 1870s by German immigrants but was abandoned after they fell on hard times. With everyone gone, the perfectly intact enclave was vulnerable to vulture developers—until an architecture student kayaking down the river in 1974 rediscovered it and campaigned for its preservation. (It was annexed by the city of New Braunfels in 1979.)

I drop my bags at the Gruene Mansion Inn, a Victorian manor built by town founder and cotton farmer Henry D. Gruene. Like many buildings here, it’s on the National Register of Historic Places. I walk two doors down to the Gristmill River Restaurant and Bar, which is housed in the ruins of a cotton gin, beneath the old Gruene water tower. I find a table overlooking the river just in time to watch the sunset and order a chicken-fried steak and a slice of pecan pie.

Lured by the music next door, I dip into Gruene Hall, Texas’s oldest continuously operating dance hall. Built in 1878, it has hosted many a musical legend—the photos on the walls show the range, from Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley to Garth Brooks and Willie Nelson. Tonight, under the pitched roof, dancing couples sway to a cover of The Band’s “Up on Cripple Creek.”

The wind outside carries the whistle of a passing train, and it’s time to hit the hay. I take the last sip of my Lone Star beer and walk back to the mansion. By the river, in the shadows, a buck walks past me, about 15 feet away. His spread of antlers is higher than my head. Startled, I gasp, “Oh dear!” and he pivots his head toward me. For a moment we lock eyes, before he continues on his way.

Texas has surprised me at every turn. It’s different from what I thought I knew, what I’d read before arriving. I’m reminded of something Patricia Moore said to me at Dixie Dude Ranch: “History here is an oral and visual history. It is not something on a piece of paper. But once you’re here, you see, hear, and feel the history. And it grabs you.” Feeling hugged tight, I’m already scheming to come back.

Next Up: Three Perfect Days in Arizona