Oahu is known as The Gathering Place, and it sure lives up to that nickname. While it’s just the third-largest of the Hawaiian islands, more than 65 percent of the state’s residents live here, with nearly 10 million visitors arriving each year. This tropical paradise in the middle of the Pacific would be an easy place to while away your days drinking mai tais on the beach—and the beaches are heavenly—but there’s so much more to experience: traditional and modern arts, a global food scene influenced by local ingredients and an influx of immigrants, dramatic landscapes millions of years in the making, rich history and culture… Since you’ve come all the way here, why not dive in?

Day 1

Forest bathing, vibrant street art, and an unforgettable sunset in Honolulu

I awaken at the edge of wetlands fit for a king. Or, rather, a few floors above where they once were. Until the early 20th century, an abundance of springs and streams naturally supplied freshwater to Waikiki (which means “spouting freshwater”). Taro patches and fish ponds carpeted the area, feeding the ali‘i (Hawaiian nobility) and the guests they entertained in their coconut groves and gardens. This coastal neighborhood is still world-famous for its hospitality; it remains the top tourist destination in the state. But, scanning the street scene from my ninth-floor lanai at the Surfjack Hotel & Swim Club, it’s clear that a lot has changed.

I’ve just returned home to Oahu after living abroad, and I’m ready to reconnect with this place, beyond the concrete and city skyline.“Need a bath?” asks my longtime friend Elena as she pulls up in front of the hotel to pick me up. She’s not concerned with my personal hygiene; we’re heading to Manoa Valley for a forest bathing experience. But first: fresh malasadas (Portuguese donuts) and chocolate macaroons from Leonard’s, Hawaii’s original malasada bakery, en route.

Cruising up Manoa Road, we leave the buzz of the city and its high-rise buildings behind. Sunlight flickers through the nearly neon trees that line the winding lane to Lyon Arboretum, a 200-acre botanical garden tucked into the foothills of the Ko‘olau Mountains.

Just five miles from Waikiki, we’ve arrived in another world. We meet Phyllis Look, our forest therapy guide and a lifelong Manoa Valley resident, in the shade of a gazebo, where she explains that the term shinrin-yoku (“taking in the forest atmosphere”) was coined in Japan in the 1980s, although the practice isn’t new. Humans have long found healing in nature, and forest bathing is a way to reestablish our innate connection to the natural world. “Free medicine, no side effects,” she says. As we walk through the garden, Look leads us through a series of questions to help us tune in to the “pleasures of presence”: “How would you cross this bridge if you were 5 years old? ” she asks. I forgo the walkway and climb the outside railing—I’m feeling younger already. “Listen to the sounds of this place,” she suggests. “What do you notice? ” The Oahu ‘amakihi (an endemic honeycreeper) calls. Leaves rustle in the wind. “Open your eyes and see what’s in front of you, as if seeing it for the first time.” Taro leaves bob left to right, butterflies flit about, birds swoop and soar, while clouds sail across the sky. I feel so overwhelmingly interwoven, I half expect to find roots sprouting from my feet.

We gather to share final thoughts under an ‘ulu (breadfruit) tree so heavy with fruit it appears to be reaching down to offer some. Our anthropomorphizing, it turns out, aligns with local lore. “According to Hawaiian legend, ‘ulu is a gift from the god Ku,” Look says, “The story goes that when he saw his village suffering a famine, he planted himself. Where Ku was, the ‘ulu tree grew, fed them, and kept them alive.” On cue, my stomach rumbles, and we bid aloha to our guide.

Elena and I drive back toward town, stopping by South Shore Grill for a plate lunch. Typically consisting of meat or fish, rice, and macaroni salad, it’s a meal that emerged to provide quick sustenance for workers during the plantation era. I polish off the fish plate—grilled ono with macadamia nut pesto, island slaw, and rice—and realize the ocean is so close I can smell the saltwater. Or is that all the surfers dining beside us?

Elena drops me off in downtown Honolulu at Iolani Palace, a restoration of the royal residence that was home to Hawaii’s last two monarchs: King David Kalakaua and his sister and successor, Queen Lili’uokalani. The palace was the center of the kingdom’s government and a symbol of innovation—it had electricity years before the White House. Following the 1893 overthrow of the monarchy, Queen Lili’uokalani was imprisoned here and accused of treason for her efforts to peaceably restore Hawaii’s sovereignty.

In many ways, the building remains a symbol of pain due to the loss of the Hawaiian kingdom and identity—the language, culture, and traditions were outlawed during that time and have taken more than a century to revive—so it’s important to visit. “It symbolizes the heart of the kingdom,” says John De Fries, the president and CEO of the Hawaii Tourism Authority and a Native Hawaiian.

I’m late (or just on island time?) to meet Jasper Wong, cofounder of the community art center Lana Lane Studios, in Kaka‘ako. I’m only a few blocks from Iolani Palace, but it seems I’ve time-traveled a hundred years. The neighborhood hums with cute eateries, artisan shops, and street art in every direction: murals of Japanese-style cartoon characters, honu (Hawaiian green sea turtles), and more. And where street art goes, Instagrammers follow. There are full-on photo shoots in progress, and is that … a wedding? Wong helped nudge this “forgotten district” toward becoming the destination it is today by creating Pow! Wow!, a nonprofit that invites artists to splash eye-popping murals onto Kaka‘ako’s industrial walls. What began with one mural at the first Pow! Wow! Hawaii event in 2011 has grown to more than 100 murals throughout the islands and multiple events around the globe. “Sometimes the process is more interesting than the final piece,” Wong says.

There’s not enough time to see them all, and I’m ready for a respite from the sun, so I duck into Highway Inn for a snack. This location opened in 2013, but the name is much more venerable. Seiichi and Nancy Toguchi opened the original restaurant on Oahu’s west side in 1947, and now their granddaughter Monica is at the helm. I want to eat everything, but I’ve promised to meet Elena at the beach for sunset, so I sample some lomilomi salmon, poi, and laulau before returning to Waikiki.

The sweet scent of plumeria and the soothing sound of slack-key guitar reach me before I enter Duke’s, a beachfront spot named after the legendary Hawaiian surfer and swimmer Duke Kahanamoku. I weave through a sea of sunkissed guests to the Barefoot Bar, where I see that Elena has scored prime real estate: a lanai table with views of the surf break and Diamond Head.

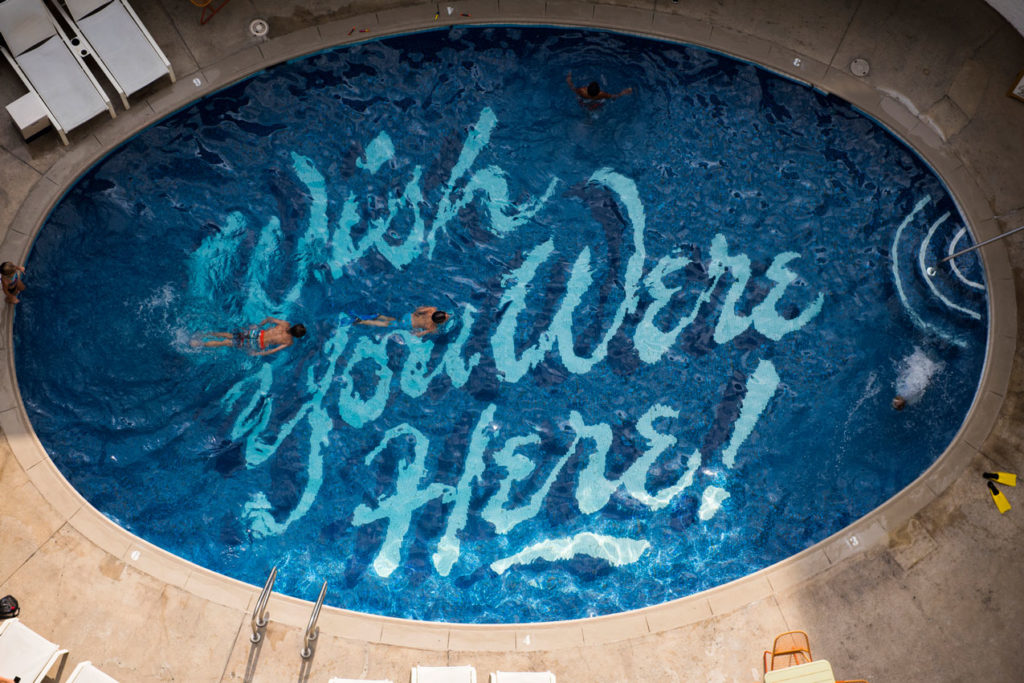

The glass of Lokelani rosé she hands me pairs perfectly with the sherbet-colored sunset in front of us. Once the last bits of light fade to night, we head back to the Surfjack, where we’re welcomed by a poolside ukulele player. We grab a picnic table and order pohole (Hawaiian fern) salad and ‘ulu pupus from the hotel restaurant, Mahina & Sun’s.

When the musician finishes her set, we join the crowd in cheering “Hana hou!” (“Do it again!”) She obliges, and so do we, ordering one more drink—a liliko‘i (passion fruit) cocktail called a Here Comes the Sun. On the contrary, I’m ready for bed.

Day 2

A heavenly drive, a hot hike, and handmade crowns along the windward coast

No one has ever used the words “morning person” to describe me, but today, I’m too excited to sleep and am up before the sun. With an empty picnic basket and a full day ahead, I meet Elena at the KCC Farmers Market, where we snag pineapple and papaya, taro chips, macadamia nuts, chocolate, and two Koko Crater coffees—all made in Hawaii. We chase an intoxicating aroma of lemongrass and curry to The Pig & the Lady, a Vietnamese street food tent, where we order a banh mi and bun xao to go.

Cruising toward the eastern side of the island, we pass Koko Head (and hikers tackling the 1,000-plus steps up the slope—now, those are morning people) on the left and Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve on the right. “How does anyone keep their eyes on the road? ” I wonder aloud, as we snake along the dramatic Ka Iwi Coast. From the sapphire horizon to a mix of mint green and electric blue near the beach, the Pacific Ocean’s palette is so varied and vibrant I have to blink to be sure it’s real. Elena laughs. Luckily for us both, she’s the one at the wheel.

We pull off at Halona Blowhole Lookout. After watching seaspray bursting up from the lava tube below, we take our towels and picnic basket across the lot and make our way down to a sandy spot nicknamed Eternity Beach after its appearance in From Here to Eternity. It’s perfect for our picnic but, judging by the way the water is seesawing about, not for a swim today.

Bellies full, we climb back up the rocky trail to the car. We hit the Makapu‘u Lookout (another pict ure-perfect scene: sea cliffs, Makapu‘u Beach, and the islands of Manana and Kaohikaipu, both state-protected bird sanctuaries) and then Waimanalo Bay for a swim before driving to Lanikai. The Ko‘olau Mountains en route look like emerald-colored curtains hung from the clouds.

Once in Lanikai, we lace up our boots and follow the handmade signs to the Pillbox Trail. The beginning of the path is steep, but a couple of minutes in we reach a landing with sweeping views of Lanikai and the Mokulua islands. The air is still. And wet. Sweat beads on my forehead. Fortunately, even with multiple “It’s so beautiful! Can we take a picture? ” stops along the way, it takes only about 30 minutes to reach the namesake military pillbox bunkers at the top. I turn in place for the 360-degree view so many times I’m dizzy. (Or that could be the heat. I take a big swig from my water bottle just in case.)

We didn’t come just to stare at the ocean; we need to get in, so back down the ridge we go. I’m the type to tiptoe into the water. But Lanikai, with its soft sand, cyan sea, and graceful palms, seems to whisper, “E komo mai” (welcome). I rush in and lie back, toes peeking above the water. I contemplate canceling our plans and staying like this forever. Bobbing along weightless in the water with our faces to the sky, I can hear Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole singing in my head: The sound of the ocean soothes my restless soul. The sound of the ocean rocks me all night long… I’d better get out before I fall asleep.

We head into Kailua, grab a table at Uahi Island Grill, and sip liliko‘i margaritas while waiting for the main attraction: red curry fish on a mound of rice, topped with a tangy green papaya salad. “There’s no way I can eat all of this!” I say when I see the size of the dish. “I kind of want more,” I say when the waitstaff returns and finds the plate wiped clean.

As we drive farther up the coast, time seems to slow. Less traffic. More trees. Smaller houses. Fishermen casting lines along the shore. We’re so close to the water, I imagine that if the tide comes up, it could wash over the road.

In La‘ie, we locate the house where Auntie Pat and Kiana, the mother-daughter duo at O’ahu Leis, offer lessons for making lei po‘o, lei for the head that are often worn for celebrations.

Kiana’s 2-year-old daughter, Kohai, runs out lashing a grin, then turns back toward the house, waving for us to follow to the backyard, where fresh-cut leaves and flowers are laid out—ti leaves, crotons, song of India, bougainvillea, plumeria, bird of paradise petals. Kiana explains that her mother started making lei po‘o for her and her sister when they were dancing in keiki luaus.

Auntie Pat, who is originally from Tahiti, didn’t adorn her daughters in the typical lei po‘o of that time but in a bigger, bolder, more Tahitian style. “Her style is a rainbow of colors,” Kiana says. “Unpredictable. Big flowers here, small flowers there. A HawaiianTahitian fusion. She’d always have one ready for us for every event. Now, I see it was a labor of love; it takes so much time and is made to show aloha to someone.”

Kiana demonstrates the wili (wrap) technique, using the lauhala leaf and raffia. I’m only a few flowers in when my hands start cramping and my raffia breaks. Auntie Pat adds a new strand and swiftly wraps in several bouquets. We carry on: two leaves, small bouquet, wrap, wrap, repeat. Kiana ties the lei po‘o around our heads and hands us a mirror. Big and bold.

We thank Auntie and Kiana, take our lei po‘o—and an appreciation for the aloha bound up in them—and hit the road, rounding the island’s North Shore. We drop by The Elephant Truck at Sunset Beach for pad thai and Panang curry, the balance of distinct flavors reminding us of the variety of foods, people, sights, and experiences we’ve encountered on Oahu.

We’ve barely driven 40 miles, yet we’ve experienced the world. We check in at Ke Iki Beach Bungalows just as the sun is starting to slip below the horizon and walk—lei po‘o on our heads, aloha in our heartsdown to the sand. The sound of the ocean soothes my restless soul. The sound of the ocean rocks me all night long…

Day 3

Sand dunes, ‘small kine’ waves, and aloha ‘aina on the North Shore

I wake to a text from the surf instructor I’m scheduled to meet later: “Surf came up a bit, so we’re moving your lesson to a protected cove.” I’m not sure I want to find out what “a bit” means; the first time I tried surfing on Oahu was 15 years ago, when a local friend took me out, promising the waves were “small kine.” I got pummeled and was too petrified to ever try surfing again. I contemplate canceling for today but decide to take a chance that this will be the day I finally replace bad memories with better ones.

Elena and I drop by The Sunrise Shack, a health food hut across from Sunset Beach, to meet cofounder Koa Rothman, a professional big-wave surfer who’s happy to chat about his love of the North Shore. “In the winter, it’s the biggest gathering of professional surfers in the world,” he says. “It’s a special place.” I’d love to bottle his chilled-out energy and fearlessness (he’s surfed waves as big as 60 feet and survived serious wipeouts, and he still goes back out), but I’ll take the next best thing: something ‘ono (tasty) from the Shack. Koa says he usually has an almond bullet coffee before he surfs and an acai bowl with almond butter and strawberries after. We’ll have the same—hold the big waves, please.

Elena and I hop in the car and drive west until the highway ends at Ka‘ena Point Trail. This lava rock coastline dotted with hidden coves—silent save for the birds, wind, and waves—is the stuff you think exists only in dreams. But here it is. About 2.5 miles down the trail, we reach Ka‘ena Point State Park, one of the last intact dune ecosystems in Hawaii. Two fishermen pass, and we ask if they caught anything. “Dinner,” they reply with a smile. I turn, and the view nearly knocks me over: Both coasts are visible, and we’re standing at the apex. Clouds drift over the Wai‘anae mountains and beams of sunlight stream through. I close my eyes as if they’re a camera shutter—I need to hold on to this. It’s time to head back for my surf lesson.

We meet Carol Philips, owner of North Shore Surf Girls, at Pua‘ena Point. Safely on the sand, she demonstrates how to paddle, turn, and pop up, then asks me to do the same. “You can ride all the way in like this if you want,” she says, modeling a cobralike position. “You don’t have to stand up until you’re ready.” We put the boards in the water, and a sea turtle swims toward me, turns and glides under the water in front of me, then loops back out toward the surf, as if leading the way. I can see sets rolling in, and my heart starts thumping against the board. “I’m right here with you,” Carol says.

We arrive at the lineup, and almost immediately she says, “Turn your board toward the beach. Check over your shoulder and get ready.” I thought I’d have more time to watch and wait and, I don’t know, breathe? “Paddle!” she yells. “Paddle!” I feel the wave start to lift the back of the board. I push the tops of my toes down and lift my chest up. You can ride all the way in like this if you want. It would be easier. But I don’t want to do what’s easier. I want to surf. I’m picking up speed and hoping the momentum will carry me. I pop up—not perfectly, but I’m up. I find my balance and keep my eyes on the beach. I feel like I’m flying. I hear cheers behind me. The wave dies out, so I lie down on my board and look back to find Carol riding in on another wave. “How was that? ” she calls. “Was I standing up? And, um, were people … cheering? ” “Yes!” “For me? ” “Yes!” We laugh and paddle back out to catch a few more waves before returning to the beach.

Just as we reach the shore, a turtle pops its head out of the water, then swims away. I can’t be certain it’s the same one that greeted us earlier, but it sure does seem like a send-off. Ready to refuel, Elena and I drive into Hale‘iwa and stop at Surf N Salsa, a food truck serving Mexican-style dishes made with local produce. I practically inhale the crispy fish tacos, pausing only to drizzle homemade salsa over the top. We also swing by Kula Shave Ice, where I order an organic guava shave ice with a haupia cream top.

Next, we’re off to talk with Felicita “Ku‘uipo” Garrido at Na Mea Kupono, a lo‘i kalo (taro patch) in Waialua. Na Mea Kupono (meaning “all things proper, or rightful”) is more than a farm. “Our focus is not just kalo cultivation,” Garrido says, “but living the values of aloha and sharing this space so people can connect to the ‘aina (land) and their ancestors.” In the Hawaiian creation story, Wakea (“sky father”) and Ho‘ohokulani (“the making of stars in heaven”) had a stillborn baby. They named him Haloanakalaukapalili (“the quivering long stalk,” so called for how taro leaves bob in the breeze) and buried him. Ho‘ohokulani’s tears watered him, and kalo grew. Wakea and Ho‘ohokulani had a second son and named him Haloa after his brother, feeding him the kalo. “That’s where the connection began,” Garrido explains. “The older brother sustained his younger brother, and the younger brother must malama [care for] his older brother. Aloha goes both ways: You take care of me, and I take care of you. We’re all connected.”

On the way to the lo‘i, we spot some ‘alae ‘ula, an endangered Hawaiian moorhen. “What a blessing!” Garrido says, counting five of them. “You must have good karma.” Tasked with clearing invasive species, I step into the lo‘i. I’m up to my waist in water, sinking in the mud. Rain begins to fall. Although it’s my first time in the lo’i, there is something familiar: the feeling of being part of, not separate from, my surroundings, just as I experienced while forest bathing.

With my feet now buried in the mud, I’m almost certain I could sprout roots. The rain stops just as we finish, and we go to the punawai (spring) pool to rinse off. We have a dinner reservation at local favorite Haleiwa Joe’s, but as the sinking sun casts an ethereal light over the lo‘i, I’m in no rush to be anywhere else. I test the water with my toe. It’s frigid. “You don’t have to go all the way in if you don’t want to,” Garrido says as the rain starts to fall again. I didn’t come here just to dip a toe in; I came to immerse myself. So I do.