A term that’s often used to describe India’s capital city is “organized chaos.” This concept applies to every aspect of Delhi: the crowded streets, the boutiques and art galleries coexisting with centuries-old ruins, even the steady rhythms of the fruit vendors and chaiwalas traversing the city with their wares.

As the capital, Delhi is home to some of the subcontinent’s most famous sites, such as India Gate and Red Fort, but it also bears the scars of colonization—centuries during which it was divided and redeveloped in the name of the British Raj. In recent years, however, the city has undergone a transformation. Interwoven among the stately buildings and relics and beloved food stalls are new restaurants, markets, and developments that are leaning into India’s bountiful heritage. Instead of gazing outward, Delhi, it seems, is finally looking inward.

Day 1

Exploring Old Delhi’s mosques, street food stalls, and spice markets

There is no better way to deal with jet lag than to dive headfirst into the belly of the beast. Here, that means Old Delhi—the former capital of the Mughal Empire and, as the name suggests, the oldest part of the city. Old Delhi is 1,500 acres of sensory overload: rickshaw horns blaring, frying pooris giving off their nutty scent, and throngs of people (about 20 percent of the city lives here) weaving through narrow alleys and bustling streets.

But first, I load up on breakfast at The Oberoi, New Delhi, a venerable hotel right in the heart of the city. The spread is vast and varied, but I’m here for the idli, fluffy steamed rice cakes that taste like miniature clouds, served with a side of sambar (a tangy lentil and tamarind soup) and coconut chutney. To drink, a cup of milky, cardamom-laced chai. No one does mornings quite like Indians.

I’ve been visiting this city every couple of years since I was a kid. Also, I recently wrote a cookbook, Indian-ish, which features recipes partially inspired by what my parents ate growing up near Delhi. Indian culture normally dictates that I stay at my aunt’s place, so it’ll take some time to adjust to having a spacious room (and an automated toilet!) all to myself. But I’m excited to explore the city on my own for the first time.

After breakfast, I meet up with a Tours by Locals guide, Vishnu, and we take a short drive to Old Delhi. Along the way, we pass seventh-century ruins and the moat-lined stone wall that separated the palace complex from the rest of the city during Mughal times. I know we’ve reached our destination when we begin to share the road with cows and sugarcane juice vendors. Our first stop is one of India’s largest mosques, the Jama Masjid, which was completed in 1656 to house relics of the prophet Muhammad. I can’t help but compare the breathtaking structure—soaring red sandstone minarets, white marble domes, lines from the Quran carved in black onyx, a wide courtyard—to the Taj Mahal. “There’s a reason for that,” Vishnu says. “Same architect.” That is, Persian visionary Ustad Ahmad Lahori, whom emperor Shah Jahan commissioned to design both.

From there, we take a brisk walk into Chandni Chowk, a busy stretch of markets where people are hawking everything from silver jewelry to gulab jamun (rosewater-dipped milk balls). I want to stop and browse at every stand, but Vishnu is on a mission—he wants to show me the havelis, centuries-old townhouses known for their elaborately decorated doors. I see one etched with incredibly detailed roses, another that’s bright blue and outlined in mint-green vines. It’s amazing that these painstakingly crafted relics are lingering in plain sight—you just have to know which alley to duck into.

That last part is tricky, because Chandni Chowk has a lot of alleyways (galis, in Hindi). I have my stomach set on one in particular: Paranthe Wale Gali, which is home to a cluster of stands that sell only stuffed breads called parathas. Vishnu directs me to the oldest of them, a simple setup with just a few tables and no decorations that dates back to 1872. The sign out front says, “Minimum Two Parathas are Necessary.” That won’t be a problem. I order two stuffed with paneer, a mild, non-melting Indian cheese, and watch as a cook rolls out the dough, folds in crumbled paneer dotted with fenugreek and coriander, rolls it out again, and then slides it into a pan filled with ghee. It’s served alongside sabzis (stewed vegetables). I tear a piece off and dip it into a pumpkin sabzi. It’s a rich, crisp, spicy, and slightly sweet mess.

I’m struggling to keep up as Vishnu bounds through the crowded streets. Here, pedestrians occupy the same space as animals, rickshaws, and cars. “Walk like an Indian,” Vishnu advises as he charges into traffic. Rickshaws magically get out of the way. “It’s about walking confidently.” I try my best to mimic him, but I can’t help but flinch at oncoming cows.

On Khari Baoli, one of the district’s most bustling streets (and that’s saying something), we browse a spice market, with its fragrant bags of cardamom pods and saffron threads, and then I pick up a vial of saffron perfume at a 100-year-old perfumery. My stomach rumbles. After all that walking, I’m hungry again.

I’ve been told that Karim’s kebab house in Chandni Chowk is the spot for the city’s finest grilled meats. The unadorned restaurant was started more than 100 years ago by the son of a chef who had been a cook in the court of the Mughal emperor, and the seekh kebabs are appropriately splendid. The glistening cubes of beef speckled with cumin and coriander are so tender they literally fall off the skewer.

After our (second) lunch, Vishnu motions me to follow him up a flight of stairs a few blocks from the restaurant. We ascend all the way to the rooftop, which yields a spectacular view. The entire city unfolds before me, from the grandeur of the Jama Masjid to the ornately decorated balconies of Chandni Chowk to the palatial government buildings freckled throughout New Delhi.

Back at street level, I spy a group of plumbers, electricians, and carpenters napping in the shade, awaiting customers. “It’s a good system,” Vishnu insists. “If you need a plumber, you know exactly where to find one.” I’ve started adjusting to the pace of Old Delhi, but looking at those snoozing handymen, I’m reminded that I could use a nap too. Back to the hotel.

When I wake up, it’s time for dinner at Indian Accent. The famed tasting menu restaurant by globe-trotting chef Manish Mehrotra is a far cry from Old Delhi—the dining room is spacious, serene, and dimly lit, with a certain earthy glamour. A parade of dishes appears: pepper crab topped with idiyappam (crisp rice noodles); pork ribs laced with Old Monk rum and mango pickle; and for dessert, makhan malai, impossibly light saffron cream topped with rose-petal jiggery brittle and almonds. “The idea is to do pan-Indian regional food, but make it new,” Mehrotra explains as he serves the last course. “The presentations and combinations are unique, but it is all rooted in the food I grew up eating.”

Belly full, I head back to The Oberoi and crawl into bed. I may be stuffed, but I’m already looking forward to everything I’ll eat tomorrow.

Day 2

Checking out a famous fort, a gorgeous garden, and a giant jewel

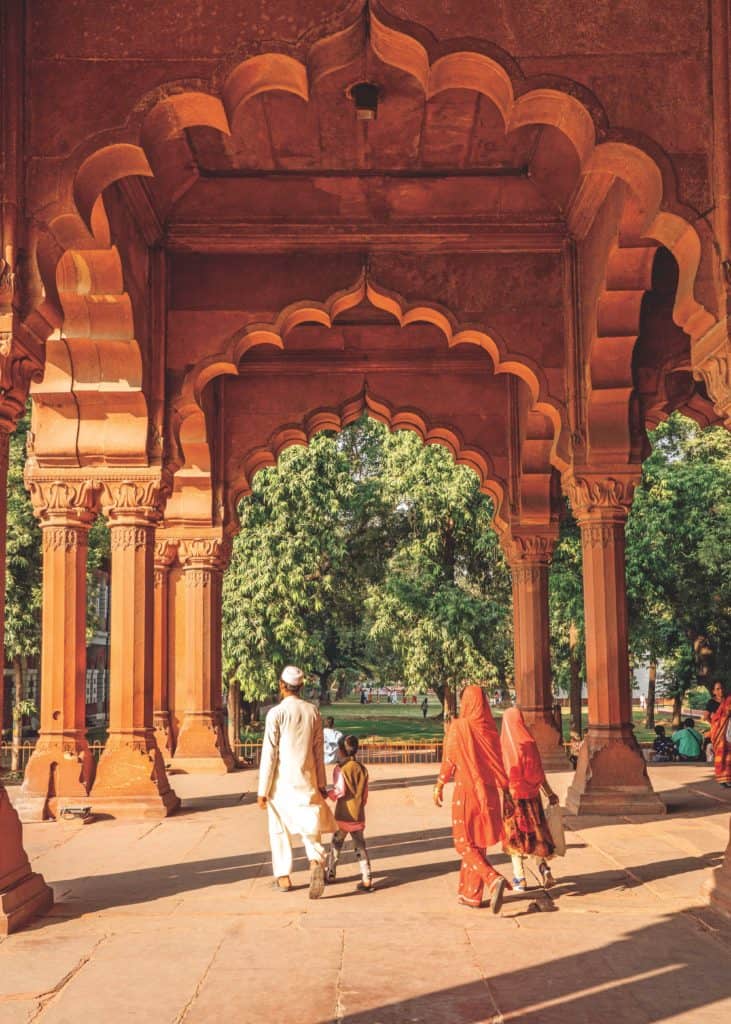

Today starts with another round of idli and sambar. I could get used to this. Post-breakfast, my driver (it’s relatively cheap to hire one, and you can usually book through your hotel) takes me to Red Fort, a fortress that was the Mughal emperors’ primary residence. Considered by many to be Delhi’s most important monument, it’s surrounded by a mile and a half of imposing red sandstone walls, with ornately carved domes and tall watchtowers. Inside, I explore the houses of the Mughal royals: Rang Mahal, which was home to the emperor’s wives and was once painted in bright colors and decorated with mirrors; and Diwan-i-Khas, where the emperor doled out justice from his bejeweled Peacock Throne (which was stolen in the 18th century).

Next on my list: Humayun’s Tomb, which was built in 1569 to honor Emperor Humayun. With its triptych-style facade capped by an imposing dome, the tomb served as inspiration for the Taj Mahal, which was erected nearly a century later. As I get closer, I can see all the tiny details that make the 154-foot-tall structure so stunning: the complicated marble inlay patterns that line the facade, the latticed windows where light streams in. Surrounding the building is an almost artificially green garden.

Speaking of gardens, you might be surprised to know that Delhi—a city known for its crowded streets—is full of public parks. I’m off to see the most famous one: Lodi Garden, which was both a garden and a tomb for the rulers of the 15th- and 16th-century Lodi dynasty. By the time I arrive, the sun is out, and the infamous Delhi heat is arresting. It’s well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and I’ve soaked through my T-shirt before I pass the entrance. That doesn’t stop me from being amazed by the little differences in design from all of the other structures I’ve seen. The tomb of the ruler Muhammad Shah, for example, is octagonal, and the dome is topped with a lotus flower. Around me, I see couples cuddling on benches and elderly aunties out for a stroll, admiring all the native tree varieties.

I’m melting, though. Time for indoor activities.

Back in the car, air conditioner blasting, we drive by India Gate, another of the country’s most famous landmarks, a memorial to Indian soldiers who died fighting in World War I. A sturdy 138 feet in height, it’s an anchoring point of the city. We drive around the entirety of the monument, which is crowded with tourists taking photos. I’d do the same, but I’m still drying out. Also, I’m hungry.

I meet up with my aunt Manisha, who has lived her whole life in Delhi, at Café Lota. We’re more than a decade apart in age, but when we’re together we gab like old college friends. Warm, bubbly, and open to eating anything, she is also the perfect dining companion. Housed in the National Crafts Museum—a celebration of India’s rich history of artisans and textiles—the breezy, indoor-outdoor café serves hyper-regional food showcasing the country’s range of heritage lentils and grains. There’s corn dhokla, savory fermented cakes from Gujarat adorned with crisped curry leaves, mustard seeds, and a fiery tomato chutney; cheela, a tangy pancake made of millet flour studded with chilies, paneer, cilantro, and green beans; and bhatt ki churkani, a stew of a local variety of black bean paired with rice and spicy potatoes. The flavors are wildly vibrant—unlike anything I’ve had before. I want to order even more food, but Manisha cuts me off. “We can barely fit what we have on the table,” she points out.

The two of us digest our meals with a spin through the museum, where I find an early-20th-century purple sari embroidered with hunting scenes in gold thread. I’m also enamored of two hamsa (swan masks) from West Bengal, used in classical dance.

I’m exhausted, but Manisha wants to check out the National Museum—an exhibit called Jewels of India is showing 173 gems and items of jewelry made of precious stones found in India. I’m dazzled by the main attraction, the 184.75-carat Jacob diamond. I also fall in love with a seven-string pearl necklace called a satlarah. Suddenly, my J. Crew silver chain isn’t quite cutting it.

My dinner reservation is at NicoCaara, located in the Chanakya, an upscale mall in Chanakyapuri. The restaurant is a collaboration with the chic Delhi clothing brand Nicobar, and the space is appropriately stylish, with botanical wallpaper and plants in gold pots hanging from the ceiling. Cofounder Ambika Seth is one of only a few restaurateurs in India focusing on local sourcing: The goat cheese comes from Rajasthan, the avocados from Bengaluru. “We have this colonial hangover based on this strange complex that imported was always better,” Seth tells me over a plate of nutty zarai cheese, made at a farm in Uttarakhand, near the Himalayas. “That’s changing with my generation.”

The rest of the meal is a pageant of bold flavors—orecchiette with fresh pesto made using basil grown at Seth’s organic farm, and a coconutty prawn stew from Malabar laced with rice noodles, lentils, and earthy mustard seeds. For dessert: a fluffy almond-orange cake with a dollop of not-too-sweet cream. I wish Manisha were here to try this—or at the very least to help me finish it all.

After dinner, I check into Bungalow 99, an apartment-style hotel centrally located in the Defence Colony neighborhood. The design here is minimalist and beautiful, but I barely have time to look around before my head hits the pillow.

Day 3

Marveling at the Lotus Temple, snacking on sweets, and shopping for saris

I’ve been told the place to be on Sunday is the farmers market at Bikaner House, a former palace of a maharaja that has been converted into an art gallery and cultural space. Every Sunday, vendors selling everything from fresh dosas to artisanal granola set up shop around the flower-lined entryway. Thankfully, the weather has cooled down, and I have my eye on a family-run stand called The Pickle Studio that specializes in achaar, or Indian pickles. I buy a pungent dry garlic version—whole cloves in chili powder and ghee. I can’t wait to mix it into pasta sauce.

From there, I’m off to take in one last architectural marvel: the Lotus Temple, a house of worship for the Baha’i faith. Finished in 1986, it’s new by Indian standards, but it’s already an icon, drawing 3.5 million visitors a year. The flowering lotus shape, which reminds me of the Sydney Opera House, was chosen because it’s a symbol of purity and peace. The petals of the temple are surrounded by nine pools and 26 acres of strikingly groomed gardens. Inside, light soars through the archways, directing my eye to the nine-pointed, gold-embossed star on the ceiling. Crowds of sari-clad elderly women stream by, elbowing me out of the way so they can take selfies against the backdrop of the temple.

For lunch, a few local food writers told me that one of the best restaurants in town is a tiny spot called Little Saigon in upscale Hauz Khas. Vietnamese food in India? I’m surprised. That was also the thinking of Ho Chi Minh City native Hana Ho, who came to Delhi in 2010 to cook at the Taj Palace hotel and opened this place when she noticed that there wasn’t anywhere in town to get a decent banh mi or bowl of pho. “I wanted Indian people to know Vietnamese food the same way they know Thai or Chinese,” she says. I enjoy a round of summer rolls that are a respite from the heat outside, followed by a cold noodle salad with homemade pork patties dappled with herbs. “The finishing touch,” Ho tells me as she drizzles fish sauce over the top. The noodles sing with sweetness and acidity.

For dessert, I must make a stop at Evergreen Sweet House, one of India’s most famous sweetshops and a place I’ve been frequenting since I was a kid. The store, a five-minute drive from Little Saigon, is a Willy Wonka’s factory of activity and color. People visit from all across the country to taste its fresh jalebis and ghee-soaked, fudge-like laddoos. I’m here for the kaju ki barfi, silver foil–topped diamonds of cashew, milk, and sugar. They’re soft, creamy, and not too sweet. Just perfect.

Now, time for a little shopping. First, I pop by Hauz Khas Village, where a string of eclectic shops have popped up around a historic reservoir. I duck into a vintage sign shop, Indian Art Collection, delighted by the old-school Bollywood posters, and then K.R. Stationers, where I pick up emerald-green envelopes embossed in gold lettering for friends back home.

Next, I head for nearby Khan Market—a posh retail district that’s home to some of the most expensive boutiques in the city (as well as plenty of affordable shops). I pick up a few short kurtas (loose, collarless shirts) at FabIndia and tunics at Anokhi, which is known for melding traditional textile-making methods with modern designs.

While Delhi may not be India’s epicenter of saris, thanks to the tucked-away shop Kamayani, you can peruse the full range of textiles the country has to offer, from the tie-dyed bandhani saris of Gujarat to the striped leheriya style of Rajasthan. The store’s eponymous owner buys textiles from artisans all over India who have spent their lifetimes mastering classic sari-making traditions. She shows me close to 50 different pieces, each with its own story to tell. “These saris are works of art and treasures of our country,” she says, unfolding a bright yellow linen garment adorned with orange diamonds and colorful tassels. “I am here to share those.” I’m tempted to try one on, but I don’t trust my clumsiness and mediocre sari-tying skills with the delicate fabric.

For dinner, I’m excited to try something new at Mizo Diner, which is devoted to the food of Mizoram, a part of northeast India bordering Myanmar and Bangladesh. The cuisine is heavy on rice, pork, and bamboo shoots, and it’s not well represented in Indian restaurants, but owner and hip-hop/graffiti artist David Lalrammawia is out to change that. I enjoy vawska rap, a stick-to-your-ribs smoked pork stew with leafy greens, and sawhchiar, a chicken and rice porridge served with an addictive sweet-spicy onion jam. Drum-heavy Mizo music blares on the speakers, purple graffiti lines the walls, and the entrance to the kitchen is adorned with bamboo in a nod to the traditional homes of Mizoram—a region that’s now high on my list to visit.

It’s late by the time dinner wraps up, but even at 11 p.m. the city shows no sign of slowing. Car horns honk furiously, fruit vendors crowd around me to try and sell the last of their supply, and even with no sun, the air is hot and thick.

I gobbled up all the kaju ki barfi I meant to bring back to friends and family at home, so I make one last pit stop at Evergreen to pick up more sweets. Then I head back to Bungalow 99 and go to bed dreaming of smoky pork and saris the color of cotton candy and all the things I’ve discovered in a city I thought I knew, and where I’ve still barely scratched the surface.

If you’re visiting Delhi, you really should plan a quick overnight trip to Agra to see the Taj Mahal, one of the world’s great wonders. The most direct way to get there is to hire a driver—the trip can take anywhere from three and a half to five hours, or longer, depending on traffic. You can also hop on the train, which is less expensive, slightly faster, and an experience unto itself (the New Delhi train station at any time of day makes rush hour at Grand Central Terminal seem tame). It’s best to arrive in Agra at night and wake up before sunrise to go to the Taj, as this is when the heat and the crowds are the most manageable. Also: Watching the sun rise over the mausoleum’s white domes is one of the most serene, stunning experiences you’ll ever have.

Next Up: Three Perfect Days in Tampa