Like many world capitals, Hong Kong entered the 21st century with a renewed sense of purpose. In 1997, the city bid farewell to 156 years of British colonial rule, and Hong Kongers have since experienced a period of transformation, growth, and experimentation.

Developments like Victoria Dockside and the West Kowloon Cultural District have reshaped the skyline, a shiny new train station has connected the city—symbolically and practically—with other booming Chinese metropolises like Guangzhou and Shenzhen, and next-generation tycoons (such as Rosewood Hotels’ 38-year-old CEO Sonia Cheng) are reinvigorating it from the inside out. There’s no better time to explore this place, as it remakes itself from a staid financial hub into a progressive city of tomorrow.

Day 1

Tarts, temples, and Tai Kwun

Hong Kong is a vertigo-inducing vertical city, with more skyscrapers than any other place on the planet. Especially on Hong Kong Island—the Manhattan of this 263-island archipelago—folks build skyward, turning the green hillsides into upturned combs of tightly packed towers. I wake up on the top floor of the Ovolo Central, a boutique hotel in a relatively modest 27-floor building just up the hill from the party-hearty Lan Kwai Fong district. Up here, I’m at eye level with gliding birds of prey (the ubiquitous black kites), and I suspect we have the same thing in mind: breakfast.

My goal is to eat as many buns and dumplings and tarts as possible while here, so I walk five minutes down the hill to grab a custardy egg tart at the 65-year-old Tai Cheong Bakery. For good measure, I cut across the street to the no-frills Cheung Hing Kee Shanghai Pan-Fried Buns and order the signature sheng jian bao, which are crunchy on top and squirt scalding pork broth like erupting cherry tomatoes when bitten into. They take some practice.

A few minutes back uphill sits Tai Kwun (Cantonese for “the big house”), a sprawling new cultural center that comprises the imposing colonial-era prison, courthouse, and police station, plus two new contemporary art spaces by Swiss starchitects Herzog & de Meuron. It’s the city’s biggest conservation project ever, and I hop on an English-language tour to appreciate the full scale of the place. “We called it a one-stop approach to law and order,” says the guide, as we stop under a towering mango tree in the courtyard. “A lot of police officers believed that if a tree bore a lot of fruit that year, it would be a good year for promotions. Others thought a lot of mangoes meant a lot of bad things were going to happen in the city. For police officers, those two ideas aren’t necessarily incompatible!”

I tour through the old cells (cramped!) and the new contemporary art museum (avant-garde!) and then make my way a few blocks west to PMQ, the former Police Married Quarters barracks. It’s now a multistory design incubator, where local artists sell everything from a roast goose stuffed animal to steamed bun–shaped salt and pepper shakers. Did I mention people here really love to eat? On the first floor, I stock up on kitschy souvenirs at design chain G.O.D. (Goods of Desire), but how to choose between mah-jongg-tile-print underwear and a “Dinner’s Ready” apron that sarcastically uses figures from Maoist propaganda posters?

For lunch, I hop on a Ding Ding—a double-decker, onomatopoeic tram—and head to Causeway Bay, the land of glitzy shopping malls. While most dim sum spots have all the charm of a bar mitzvah banquet hall, John Anthony is a Wes Andersonian fantasia of sherbet tones and tropical wallpaper patterns. Named for the first Chinese man to become a British citizen in 1805, the restaurant nods to his legacy with a menu of globally focused dim sum, such as Szechuan Iberico pork rolls, abalone teppanyaki, and cumin lamb dumplings. The waitress tells me to order the air-dried duck because “people love it for Instagram.” Far from a gimmick, it’s a delicious work of edible art, potato-chip-crispy shards of duck prosciutto draped over a craggy geological formation made of honey.

Coils of incense hang from the ceiling, and the air is thick with pungent smoke.

After snapping a glamour shot of that duck, I hop on the immaculately clean MTR subway line back toward Central, getting out a few stops early to take a ride on the Mid-Levels Escalator—2,600 feet of public outdoor escalators and moving sidewalks that make the hilly terrain much more manageable. Eat your heart out, San Francisco.

I stop into Man Mo Temple, which opened in 1847 to honor the literature deity Man Tai. Coils of incense hang from the ceiling, and the air is thick with pungent smoke. (Fun fact: Hong Kong means “fragrant harbor” in Cantonese, in honor of the aromatic agarwood that’s used to make incense and that once grew abundantly on these shores.) Formerly a popular spot among scholars and students, the temple is now firmly on the tourist circuit, as evidenced by the middle-aged Russian woman in a floral kimono peeking out seductively from behind a column as she poses for a portrait. A huddle of American travelers get their fortunes read by shaking incense sticks in a bucket. “Now is not the time to be making big decisions,” their guide says in a firm tone. The fortune-receiver grimaces.

I continue along Hollywood Road, past antiques shops selling intricately carved mammoth tusks (I’m skeptical), and meet up with Vicky Lau, who was named Asia’s best female chef in 2015 for her work at the Michelin-starred Tate Dining Room & Bar. After an unfulfilling advertising career (“I was doing a lot of shampoo ads,” she deadpans), Lau attended Le Cordon Bleu in Bangkok, having first gotten into cooking in her New York University dorm.

The Tate space—with its blond wood and soft pink chairs that look like strawberry macarons—is defiantly feminine. “I didn’t want something dark and trendy,” she says. “I think you should not be afraid to show who you are. If I like pink, I’m going to put in pink!” The menu is distinctly modern, something that felt radical when she opened shop in 2012. “In New York, you’ve seen a big wave of modern Chinese, but back in the day here, it was all about woks and keeping the tradition,” Lau says. “No one wanted to jump out of that. With younger chefs, we’re rethinking ingredients.” Her inventive tasting menu is inspired by, of all things, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s Odes to Common Things. “We’re paying homage to all the ingredients, the seasons, which makes things a little more spiritual,” she says. “A meal can feel like short travel.”

I order a chardonnay from China’s Yanqi region, which is improbably located in the Gobi Desert. “It’s a hidden gem,” my waiter says. The food is subtle but flavor-packed: Chinese yam with Ossetra caviar, sea scallop with aged kumquat grenobloise sauce, blue lobster with Shaoxing wine foam, steamed pigeon in a Szechuan sauce. The showstopper dessert is a buzzing beehive-shaped box containing petit fours made with honey from urban farms.

Around the corner, I stop for a nightcap at The Sea, a new cocktail den by the trio of bartenders—two Nepalese, one Indonesian—behind the award-winning The Old Man (get it?). The nameless cocktails here purport to be simple, but they’re big on flavor. I order the #5, made with peanut-milk rum, banana wine, and pineapple kombucha. It’s tropical but sophisticated, inventive but fun-loving. If they need a name, I’d go with the Tiki in a Tesla (this city’s favorite car). Or how about just The Hong Konger?

Day 2

Creative Kowloon and a tropical day trip

If Hong Kong Island is the territory’s Manhattan, then Kowloon, across the harbor, is its Brooklyn—a historically louder, messier, more vibrant, more Chinese area. It’s a place where high-end (the ultra-glam Peninsula hotel) butts up against working-class (the teeming Chungking Mansions housing complex), and one where a slew of skyline-redefining developments is attracting visitors in droves.

This morning, I’m moving my bags to the Eaton HK, a new activism-minded hotel that opened last fall on an unremarkable corner. Katherine Lo—the daughter of the Langham Hospitality Group chairman—took a gauche 1990s hotel and repurposed it for millennials, complete with a food hall and a members-only coworking space.

In the lobby, I meet the Eaton’s director of culture, Chantal Wong, a Canadian expat who’s lived here for 13 years. We step outside and look up at the facade, where the old building’s tacky billboards now display progressive art installations with messaging like “What if you were free to love everyone you choose?”

“We had these massive billboards, so we decided to curate an exhibition and do something meaningful with them,” Wong says. One was created by a domestic worker turned Magnum photographer, another by a trans Filipino university professor. “My LGBT friends would feel so proud to see that up there.”

We turn down Temple Street, where she tells me I can come later tonight to buy cheap factory goods from Shenzhen or jade—or get my fortune read. I make a mental note. We pass a blingy mah-jongg parlor with neon lights and Corinthian columns. “It’s so intimidating, very tense, neon lights,” she says. “No one has slept in three days.” I’ll probably skip that one.

I say goodbye to Wong and continue walking south to the West Kowloon Cultural District, which promises to reshape the waterfront with next year’s arrival of the $2.8 billion M+, a museum devoted to contemporary “visual culture.” Right now it’s still a maze of scaffolding and makeshift tunnels.

In the middle of the urban scrum sits the exceedingly graceful Xiqu Centre, a Chinese opera house that opened in January and is shaped like enormous parted theater curtains surrounding an open-air atrium. I’m lucky enough to have stumbled in during an open rehearsal by a traditional music ensemble. I played bassoon and clarinet from elementary school through college, but I’m totally ignorant when it comes to the instruments here: some sort of banjo, a honking trumpet, a tiny oboe-like thing that squeaks out cheerfully nasal tones. I can’t predict where the melody will go or how the chords will (or won’t) resolve, but I love how expressive it is, like a gaggle of gossiping waterfowl. On cue, a bunch of songbirds—red-whiskered bulbuls, which look like brown cardinals wearing rouge—start to land in the atrium’s trees. Walt Disney would have loved the scene.

From here, I walk a few minutes to the new West Kowloon Station. The undulating train depot, which connects Hong Kong with Guangzhou and Shenzhen, is home to the latest outpost of dim sum staple Tim Ho Wan, which is often called the world’s cheapest Michelin-starred restaurant. I order the pan-fried turnip cakes, BBQ pork buns, and springy prawn dumplings—all for about the price of a #saddesklunch back in Brooklyn.

This station has me thinking about the world outside the crowded city, so I decide to make an afternoon escape to the New Territories, a huge swath of the mainland and outlying islands that takes up about 90 percent of Hong Kong’s landmass. I have my sights set on the Hong Kong UNESCO Global Geopark, and specifically its High Island Reservoir East Dam, an otherworldly architectural achievement set on the mountainous Sai Kung Peninsula, in the territory’s far eastern stretches, once a stopover on the Maritime Silk Road.

You can get there by a subway followed by a commuter rail followed by a minibus followed by a chartered fishing boat. I decide to splurge on a taxi. Forty minutes later, the landscape shifts to tropical, as my taxi begins tracing mountain roads through jungle terrain, passing hidden coves and secluded beaches and rock formations jutting out of the sea. Do people know about this?

I arrive at a roundabout and start the half-mile hike down to the reservoir, which boasts a surprisingly diverse array of terrains within a 20-minute span: a sea cave, hexagonal rock columns that look like a curvy pipe organ, and the 1970s dam, a climbable marvel sprinkled with wide cement holes that call to mind a 20-story Whac-a-Mole board. Most impressive are the thousands of immense dolosse blocks, 25-ton concrete barriers shaped like giant jacks that are strewn here in piles to fight back against wave erosion. I stumble upon a feral cow munching on weeds under a block, which reminds me: It’s been a few hours since I’ve eaten.

I head back toward civilization for dinner at Central’s cheekily named Ho Lee Fook, the brainchild of Taiwanese chef Jowett Yu. When I arrive, a wall of gold-plated lucky cats waves me down into the basement space. Yu has said that the restaurant is meant to evoke late-night Chinatown dives in 1960s New York, but I can say from experience that the comparison doesn’t work: Everything on the menu is too nuanced and creative to make me think of drunken nights over greasy egg rolls and wonton soup.

I order the “mostly cabbage, a little bit of pork” dumplings and a decadent roast Wagyu short rib. But the standout is a simple side dish of “typhoon-shelter-style” fried corn, served beneath a mound of fragrant fried garlic, scallions, and chilies, just as Hong Kong’s boat people used to do with crab and shrimp inside their makeshift storm shelters. When I get home, I’m going to typhoon shelter everything.

But first, it’s back to the Eaton HK’s buzzy cocktail bar, Terrible Baby, where I order the Another Type of Fashion, a smooth concoction of aged coconut whiskey, espresso salt water, chocolate bitters, and Oreo chocolate syrup. Maybe it’s the Oreo syrup, but I’m feeling reinvigorated, so I head back out to Temple Street to get my fortune read.

I take a seat at a rickety table and haggle a price, and the middle-aged woman looks me over and starts rattling off rapid-fire, fortune-cookie-style pronouncements.

“You have long ears—a Buddha face.” (Thanks?)

“You will be very rich in the future.” (Thanks!)

“You have a good nose…” (Yeah?) “…so you won’t fall into abject poverty.” (Phew.)

“A lot of people are jealous of you.” (I knew it!)

“You have a good heart; you’re pretty good.” (I’ll take it.)

Day 3

A rosy morning and a rocky night

Optimistic from my late-night fortune-telling session, I’ve decided to embrace the sweet life at the city’s newest grande dame hotel, the Rosewood Hong Kong, which anchors Kowloon’s Victoria Dockside development. I arrive by carshare, and as I pull up the sloping driveway, past a monumental bronze Henry Moore sculpture, I think, I should have upgraded to a black car.

Inside, I’m greeted by a lobby that’s anything but stuffy—a perfect encapsulation of the brand’s fresh vision under its 38-year-old Hong Kong–based CEO, Sonia Cheng. Damien Hirst butterflies line the lounge, and a team of chatty butlers leave handwritten notes and chocolate-covered marshmallows from the lobby patisserie in my room. I could get used to this. No, as the fortune teller said, I should get used to this.

I drop my bags off in my room and head back down to the lobby, where I meet Olivia Tang, an energetic young guide with Walk in Hong Kong. We drive 20 minutes north from the waterfront to Kowloon City, a densely populated but unassuming district of decades-old shops and tenements. “Neighborhood tours are a relatively new thing here,” Tang says. On the drive, she tells me that she loves American TV, especially The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, whose title character has inspired her to pursue a side gig as a stand-up comedian. I ask her if there’s much of a scene here. “Local humor is a lot of play on words and slapstick,” she says, “like Jackie Chan slipping on a banana peel.”

Our first stop is the pint-size Hau Wong Temple, where Tang shows me a wall with a grid of 60 deity figurines. “This is the org chart of the gods,” she says. “Hong Kong is unique, because we have migrant gods, external consultants from Buddhism and South Asia. Temples are like 7-Eleven—the gods need to be easily accessible.”

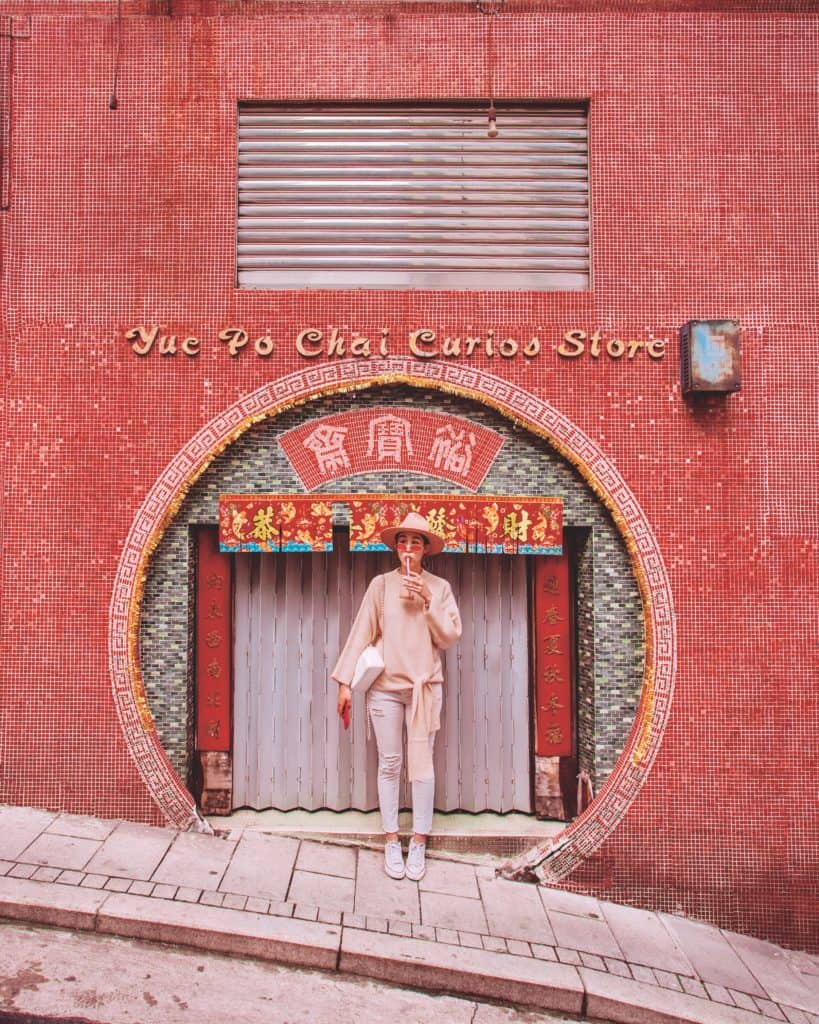

Next we step into an idyllic garden—all round moon gates and topiary dragons—that’s not quite what it seems. Kowloon Walled City Park opened in 1995 on land that was once one of the most crowded and anarchic slums on the planet, ruled by neither the Chinese nor British governments. “Kowloon Walled City was as big as five soccer fields,” Tang says. “At its peak, it had 40,000 people. It was at least 50 times denser than the densest part of Manhattan.” It was full of crime, but it was also a place of ingenuity, a functioning mini-city, home to businesses, restaurants, factories, and dwellings. Residents stole electricity from street lamps, dug wells, and rigged a network of hoses from just three faucets. Every night, “fragrance people” collected waste buckets from the tenements’ upper floors. “It was like The Wire,” she says. “If you went in, you would definitely get lost.”

Outside the walls of the old slum sits the refashioned Kowloon City—a refreshingly untouristed neighborhood of regular folks doing, well, regular things. As we stroll, we pick up snacks at beloved holes in the wall: cold soy milk and fried tofu at the Kung Wo Bean Curd Factory, which set up shop in 1960; egg tarts at Hoover Cake Shop, where, Tang tells me, “everything is made with love”; and bouncy fishballs at Tak Hing Fishball Company, a family-run operation that got its start inside the Walled City.

“I think Kowloon has more of a soul than Hong Kong Island,” Tang says, as we stop in front of Tai Wo Tang, a new café opened inside a 1932 Chinese medicine shop. “I cried when this place closed!” Now, instead of dried roots and fungi, it dishes out Tai Wo Tang lattes, a play on the classic yuenyeung (coffee-tea mix) made with Earl Grey.

All this snacking is making me hungry. I hop a cab across the harbor to Causeway Bay for lunch. Though Hong Kong officially reverted to Chinese control in 1997, not all traces of British influence are gone. Case in point: Roganic Hong Kong, one of two new restaurants by Michelin-starred English chef Simon Rogan. The tasting menu is a hearty defense against those who think all British food is bland and gravy-covered. Among the flood of courses, I sample a one-bite pumpkin tart, grilled brassica salad with cheddar sauce and truffle custard, a funky Tunworth cheese ice cream, and raw beef dressed in smoky coal-steeped oil, which tastes like the Industrial Revolution—and I mean that in the best way possible.

After a lunch this decadent, I could use a nap, but I opt instead for a relaxing Victoria Harbour cruise on the Aqua Luna II, a red-sailed junk made using old-school shipbuilding methods. I board, grab a free glass of wine, and lean back in one of the comfortable deck chairs. If not for the incongruous soundtrack—a techno remix of Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car”—I could almost feel like some pre-colonial seafarer.

All that time in the sun has earned me some post-relaxation relaxation, so I head up to the Rosewood’s sixth-floor infinity pool for an afternoon dip. Then, dinner, back in Central at Happy Paradise, the brainchild of May Chow, who was named Asia’s best female chef of 2017. Located at the top of a steep hill, the restaurant looks like a design lover’s take on the city’s ubiquitous cha chaan teng diners. The whole place is cast in a noirish pallor, straight out of a Wong Kar-wai film, with a neon display of octopus tentacles and noodle-slurping lips behind the bar. The spot is a fun-loving shot in the arm—think drag parties and a dance-heavy soundtrack—in an otherwise buttoned-up business capital.

“Are you feeling adventurous?” the waiter asks. I let him do the ordering: sourdough egg waffles with bottarga whip, stem lettuce salad with noodle-cut squid, and an umami-bomb entree of M5 Wagyu with preserved lemon rind and seaweed butter. The pièce de résistance is a custardy pig brain, which tastes like meltier bone marrow, served in a little pig-shaped urn—a piggy bank best kept away from kids.

In lieu of a nightcap, I’ve planned a night hike. Many tourists reach new heights on Hong Kong Island by taking the historic Peak Tram up to Victoria Peak. The views are gorgeous, but it’s easy going. Seeing as I’ve just eaten an entire pig’s brain, I decide to work off some calories on Lion Rock, a 1,624-foot granite mountain on the border of Kowloon and the New Territories. As the light begins to fade, I don a headlamp and follow a winding path past other hikers, the odd snake, and a wild boar rooting in the underbrush.

I’m huffing and puffing a bit as the path turns into a steep staircase and dusk turns to night. When I finally reach the peak, my legs hurt, but the view is staggering: The whole city glows golden, with high-rises stretching out toward the black of the horizon. Hong Kong has been called the City of Life, and from up here, where the buzzing urban jungle meets the real one, it’s hard to imagine another spot on earth that could ever hold that title.

Up Next: Three Perfect Days in LA